Abused and stalked, US election workers are bracing for 2024

- Published

As former US President Donald Trump and his allies face charges of plotting to overturn vote results in the state of Georgia, poll workers say false claims of ballot fraud have had an enduring impact on their lives and the country. It shows no sign of abating for next year's general election.

Chris Harvey had just worked the most exhausting months of his life helping to run Georgia's 2020 elections when he got a call on 4 January 2021 that someone was threatening him and his family.

"We hope you enjoyed this holiday because it will be your last," read the threat, posted on the dark web with a picture of Mr Harvey's home and address.

Mr Harvey, a law enforcement official turned elections director for Georgia's secretary of state, immediately thought of his wife and four children at home.

"I wasn't really worried so much for my safety as I was for my family, and stuff that might happen when I wasn't around," he told the BBC. "There's only so much that you can do."

Mr Harvey is one of several Georgia officials who found themselves at the centre of 2020 election fraud allegations perpetuated by Mr Trump and his campaign team as they sought to challenge their loss in the battleground state to Joe Biden.

The former president and 18 others are now facing 41 charges from Fulton County prosecutors related to the alleged plot. Mr Trump has denied the allegations and accuses the district attorney of a politically motivated hit job.

Unsubstantiated claims of election fraud in 2020 led to stalking, intimidation and death threats for hundreds of election workers across the country.

Those who fell victim say the allegations have ushered in an era of harassment for vote workers.

"Election officials are getting beat up left and right," said Mr Harvey. "Law enforcement has gotten better, but has been slow to recognise that threats against election officials are really threats against the entire process, and so they need to be taken just as seriously as anything else."

A 'bullseye' in Georgia

In the Peach State, some of Mr Trump's alleged co-conspirators are charged with targeting election workers.

Fulton County prosecutors accuse Mr Trump's former personal attorney, Rudolph Guiliani, in the 98-page indictment of making false statements about Fulton County Ruby Freeman and her daughter Shaye Moss, who worked at a vote-counting site.

Mr Giuliani falsely claimed the two mishandled ballots in Fulton County, a reliably Democratic district in Georgia.

Others are charged with travelling from out of state to harass Ms Freeman.

According to the charge sheet, two defendants, Illinois pastor Stephen Lee and Kanye West's former publicist Trevian Kutti, went to Ms Freeman's home to try to convince her to confess to voter fraud.

The unfounded allegations saw violent threats directed at Ms Freeman and Ms Moss, they testified last year to a congressional committee that blamed Mr Trump for the US Capitol riot.

They had to go into hiding, they told lawmakers.

Shaye Moss describes threats after Trump targeting

"I've lost my name," Ms Freeman said, "and I've lost my reputation. I've lost my sense of security."

The threats spread to Georgia's top Republican election officials, including Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger and voting system implementation manager Gabriel Sterling.

Mr Harvey, the secretary of state's elections director, said a police car had to be parked outside his house for several weeks after he received a death threat.

The state of Georgia - where Mr Trump lost by a margin of fewer than 12,000 votes - was one of the "bullseyes" in efforts by the outgoing president's team to overturn the election, said Lawrence Norden, the senior director with the Brennan Center for Justice's elections and government programme.

"As a result, there's no question that election workers in those states got more of the abuse," he said.

A rise in harassment

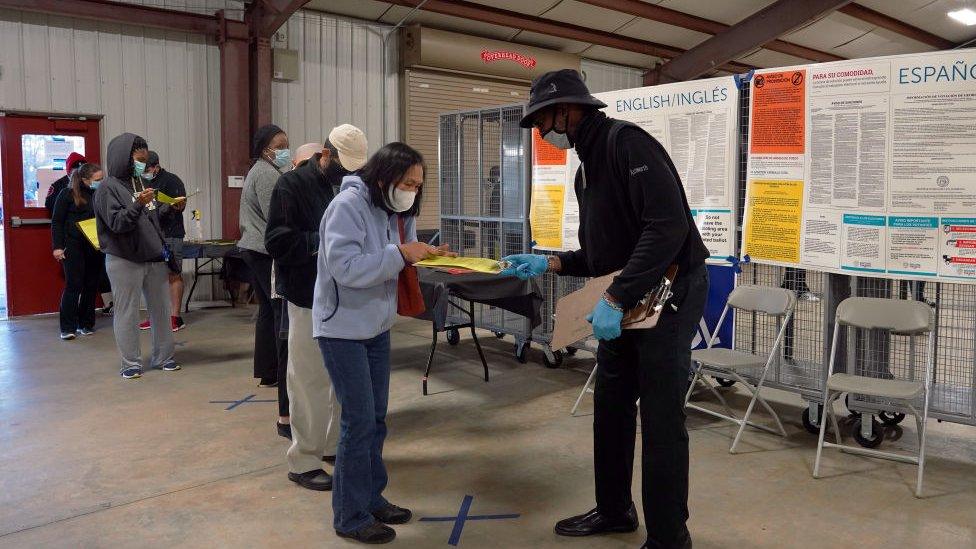

Election officials across the country have experienced an uptick in threats since 2020.

According to a 2023 poll from the Brennan Center for Justice, 30% of local election workers said they had been abused, harassed or threatened over their jobs.

Mr Norden has heard stories of a worker in Arizona whose dog was poisoned after the election and others who were forced to abandon their homes.

Many are leaving the profession because of it, he said.

"There's no question it's really been traumatic for the field and that it's impacting unfortunately who is willing to serve," said Mr Norden.

This increase in threats has so far shown little sign of abating.

Just this week, the names and addresses of grand jurors who voted in the Georgia indictment against Mr Trump were posted on a fringe website known for violent rhetoric, according to a report from nonprofit research group Advance Democracy.

Last week, a 43-year-old woman from Texas was charged with threatening to kill Judge Tanya Chutkan, who is overseeing a federal case against Mr Trump also related to the 2020 election.

The woman allegedly called the court in Washington DC and said: "If Trump doesn't get elected in 2024, we are coming to kill you."

It's yet another example of how the conspiracy theories about what happened in the last presidential election still hold a powerful grip over many in the country, Mr Norden said.

"We're going to be living with the 2020 election - and the fallout of that - in 2024," he said.

Moving on from 2020

News of an indictment in Georgia against those who perpetuated election conspiracies and allegedly harassed workers have been welcomed by some.

In a statement this week, lawyers for Ms Freeman, the Georgia poll worker, said the charges served as further evidence that "while doing their jobs and serving their community", Ms Freeman and her mother "were targeted as part of a broad, co-ordinated conspiracy to undermine the results of the 2020 presidential election".

For others, the charges brought little relief.

Deidre Holden, the director of elections in Paulding County, which covers part of Atlanta, faced violent threats in 2020, including an email warning of "detonations" at every polling site.

Ms Holden told the BBC that 2020 "changed the entire dynamic of how elections are viewed".

But she argued that Mr Trump's latest charges in Georgia would only continue to "fuel the fire of division in our country".

"I am truly shocked at the indictment," she said. "We need to learn from the 2020 election, and move on."

Others argued the country could not do so without more accountability.

Some threatening violence over elections do not believe there will be consequences, said Mr Norden.

The only way to make clear these consequences and to deter future incidents is "to indict people, to prosecute people, and to make sure that the world sees it", he argued.

Mr Harvey said he has struggled watching his colleagues face incessant harassment in the aftermath of the election, during which some workers died from Covid-19 while they carried out a logistically tortuous voting process in the midst of a pandemic.

"People have to realise that… election officials, they are people, people who are doing a good job," he said.

"They shouldn't be afforded any less justice than any other victim of crime, and people do need to be held accountable."

More on Trump's legal troubles