A shift in the life of a junior doctor in an A&E department

- Published

Katie Flower works as a junior doctor in the Accident and Emergency department at Torbay Hospital

There are more than 50,000 junior doctors in England - some are straight out of medical school, others have years of experience.

As they take part in a 24-hour walkout, the impact is being felt by thousands of NHS patients.

The strike follows years of failed talks between health service bosses and doctors' union, the BMA.

The government says it wants to make more junior doctors work weekends to improve patient safety.

Katie Flower, 28, works in Devon. Newsbeat followed her 12-hour night shift.

8pm

It's a rainy Saturday night at Torbay Hospital in south Devon, but you wouldn't know from inside the brightly lit Accident and Emergency department.

After getting briefed by other junior doctors in dark green scrubs, Katie Flower explains how she looks at the list of patients to "see how busy the department is".

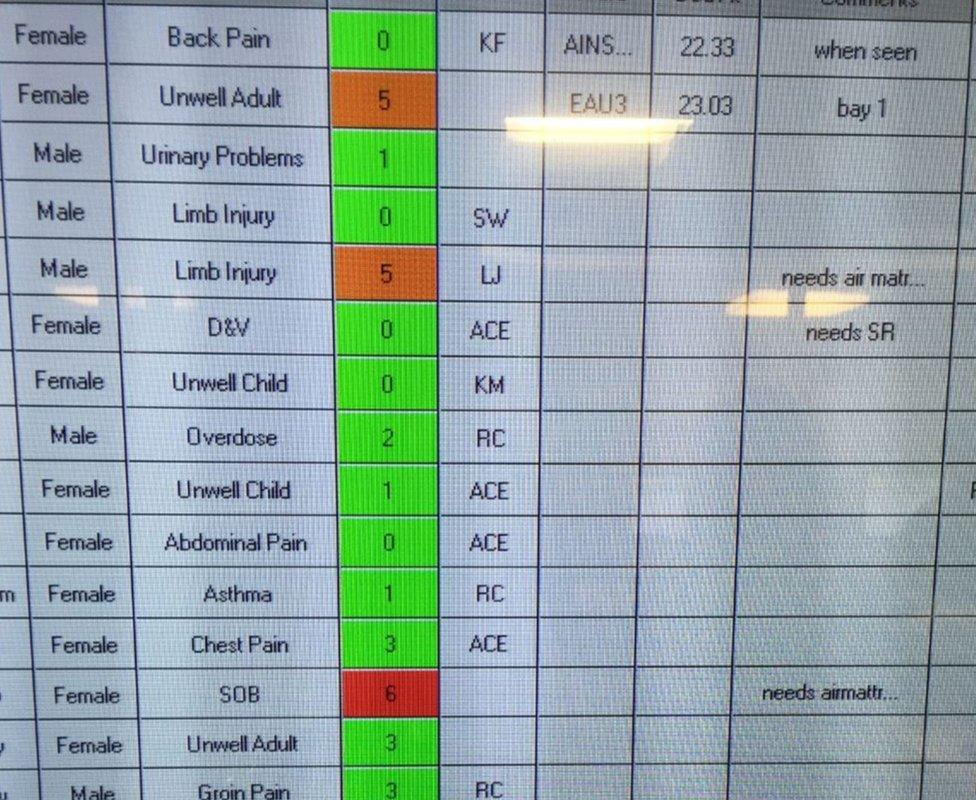

She then shows me a large screen with a list of patients' names, the symptoms they're showing and a rating out of 14 on how poorly they are.

The list also shows how long the patient has been waiting for - if it's longer than four hours the hospital is fined

8.30pm

The Sister in charge of the department tells Katie about a patient who's thought to have an infection of the bowel.

She explains it might "not be too exciting", but her records show the patient's been in hospital plenty of times before, and there's a risk of the infection spreading.

After listening to the woman explain what she was feeling, Katie sends her for a scan as it's thought she might have a compression of the spinal cord.

Katie then returns to what looks like a command centre of computer screens and enters in the details of her assessment.

The pattern of getting briefed, assessing or treating a patient, then returning to a computer was a pattern she'd repeat throughout the shift.

A lot of Katie's shift is spent entering patient information into the hospital database

9.15pm

The sound of a retro phone goes off, which staff call the "bat phone".

It's a paramedic calling ahead to warn when they're arriving with a patient who is seriously ill.

But until they arrive Katie's next concern is a patient who's thought to have had a stroke.

With his wife at his bedside the man greets Katie with a smile, and explains that his face "had gone a bit numb".

After her softly spoken line of questioning, the patient tells her he has limited movement down one side of his body but before things go any further Katie has to stop.

The patient in the next bed starts screaming with pain and making sounds like she's being sick.

Katie rushes to the other side of the curtain to help a nurse who is struggling to put a needle into the woman's arm as she can't locate a vein.

As the woman twists in pain Katie eventually finds one and it's not easy to watch.

Katie performing tests on a patient who was suspected of having a stroke - he was later allowed to go home

10pm

"Vomiting and people being in pain are quite stressful, because you know how horrible it is yourself," Katie explains.

She then moves to a side room where a man, who looks in his 50s, lies on a bed with his wife walking around the room.

He, almost nervously, tells Katie he has a history of heart problems and that he's had a sore pain in his chest since the early evening.

But thanks to the hospital's extensive database Katie already knows this.

The man's blood tests come back quickly - he hasn't had a heart attack, with Katie suggesting it could be to do with his current stress levels.

All the computers in the department later crash, which was followed by a collective groan.

Staff say police have to escort patients to the department most days

11pm

Katie rushes to the resuscitation room to see her first serious patient.

He's an elderly man, who was fine when he was last seen at 6pm. He's now unconscious though and we're not allowed in.

Katie gets in touch with the man's care home and next of kin to both explain what's happened and find out more information.

After a while Katie comes out: "He's quite an independent gentleman so this is quite a dramatic change so we need to get on and find a reason for this.

"At the moment we can't say but it doesn't look very good."

During the early hours there are around six junior doctors on duty, after 9pm it dropped to three

1am

Katie's back at her desk looking at a scan of the patient's brain. She gets a more senior doctor to get a look at it.

In the middle of the image there's a light grey circle - Katie explains that it's bleeding on the brain which is "life threatening".

Before heading back into the room we agree to part ways until the morning.

For the first five hours of the shift I didn't see her stop once, take one drink or have any food. She later told me she did have a short break at 4am.

"I usually just go straight to sleep" - Katie after her 12 hour shift

8am

This was Katie's fifth night shift of seven and when we meet again she looks surprisingly fresh and alert, although admits she doesn't feel it.

We retreat to a side room to discuss why she's going on strike and she admits she ultimately can't guarantee patients won't suffer.

At the moment statistics show you are more likely to die if you are admitted to hospital on a Saturday or a Sunday.

However, Katie thinks there aren't enough junior doctors in the first place.

"We have to look at the long term gain. If we allow this contract to go through it will be damaging to the workforce as well as the NHS."

For more stories like this one you can now download the BBC Newsbeat app straight to your device. For iOS go here, external. For Android go here, external.