How to avoid getting misled by polls

- Published

People like using polls to make a point about big issues.

Politicians use them in debates, newspapers put them on front pages and people quote them on social media.

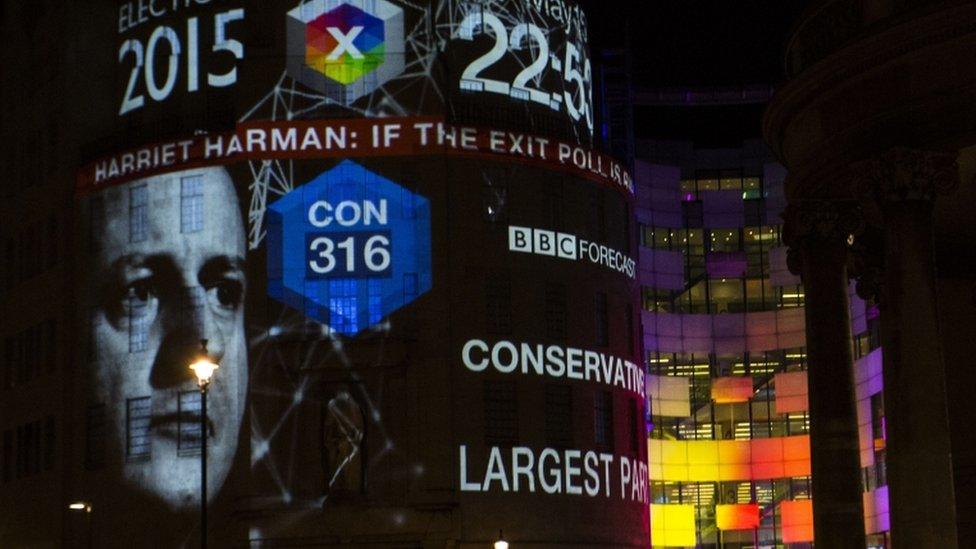

It's one reason why some people were shocked when the Conservatives won the general election.

Up until the very last minute David Cameron's Conservatives and Ed Miliband's Labour were predicted neck-and-neck.

Why were they wrong?

In a nutshell, because Labour voters were easier to get hold of than Conservative voters on the telephone and over the internet. Older Conservative voters were harder to contact and one polling company said they didn't have enough younger voters disengaged with politics on their books.

More on that here.

General elections aside, when you see big numbers talked about on television, or online, these are the kinds of questions you might want to ask.

The Sun's front cover on Monday 23 November - complaints were made to a watchdog about this surve

All polls are not created equal

Think about those hair advertisements you see where a celebrity spins around while a voiceover tells you that 87% of women agree that a certain shampoo makes your hair softer.

Sounds like a pretty big proportion of people, right?

Dr Rogers, an ambassador for the Royal Statistical Society, says it's important to look at the number of people who were surveyed.

The red thing has increased more than the blue thing but who knows what, why or how?

"If I take different samples of people I'm never going to get the same answer every single time," she says.

"The bigger my sample size, the more reliable my result is. If I've only got a small number of people in my sample then it's not as reliable an answer and it will be subject to a lot of uncertainty."

If you look at the small print at the bottom of the advertisement, you will probably see the number of people they surveyed. If something like only 97 people were asked then that's a relatively small sample.

Dr Rogers also points out that if those people signed up to do the survey, they may have a greater than average interest in beauty and give answers that do not represent the nation as a whole.

What's in a question?

"If you see 70% of women agree, that always says to me, what question have they asked them?" says Dr Rogers.

"They said to these women, 'Do you agree with this statement?'

"I think more people would probably just tick, yeah I agree with that. They might answer differently if they were given a question such as, 'How does this make your hair feel?'"

Leading questions, asking whether you agree with a statement, for example, can really shape the types of answer that are given and therefore the data is produced.

An either/or choice also doesn't offer the spectrum of emotion or opinion that people can hold.

One in five, 20% and a fifth - they're all the same thing

"Number jargon," when something is described as being increased by 17% for example, is "really unhelpful" according to Mr Moy.

"It's very easy just to put people off completely," he says.

Full Fact, external actually encourages the media to avoid using statistics in their reports unless it is strictly necessary.

News websites should also be visualising statistics more, Dr Rogers suggests, as people can understand one coloured-in figure and four blanks ones representing one in five people, much better than the phrase "20% of people" even though they are the same thing.

Where do the numbers come from?

"You don't need to be a mathematician to understand statistics," says Will Moy, from Full Fact, an independent fact checking charity.

So even if you didn't ace your maths GCSE, it's still possible for you to understand - and even question - the numbers you see reported in the media.

Advertisers may generate statistics to help make a product more appealing. Governments survey the population to inform policies for the future. Charities will promote statistics to make people aware of an issue.

"Statistics are numbers but they are little bits of information," says Dr Jennifer Rogers from the University of Oxford.

While they might help experts to "get an indication of what's going on", they also allow people to "present" and "interpret" the data in different ways.

Who can you trust?

"We're relatively lucky in this country, having official statistics that are pretty robust and independent systems for making sure they are trustworthy," says Mr Moy.

People in other parts of the world "can't take it for granted" that governments and organisations are releasing reliable data.

One of the most powerful influences on people is their social networks, Mr Moy says, so when you repeat or quote statistics online, you can be shaping the way the people you know see the world.

"The people you trust most are your friends, that's where you get your opinions from," he says.

"You don't have to repeat these numbers unless you've seen they've got enough evidence to base them on."

For more stories like this one you can now download the BBC Newsbeat app straight to your device. For iOS go here, external. For Android go here, external.