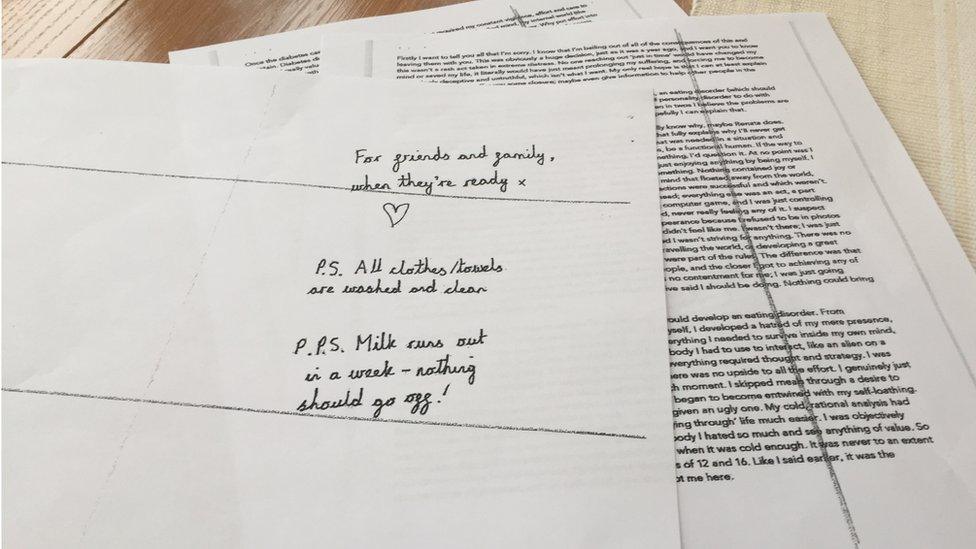

The suicide note that told Megan's diabulimia story

- Published

Just over a year ago Lesley and Neal Davison received a phone call telling them their daughter was about to be sectioned.

She'd tried to kill herself.

For years Megan had been keeping a secret. She had an eating disorder. But she hid it so well, nobody in her family ever realised.

Last month, on 4 August, she hanged herself and left a six-page suicide note.

Megan, who was 27, had diabulimia.

The term refers to the combined impact of type 1 diabetes with an eating disorder.

The condition is not yet medically recognised.

Watch - Diabulimia: The World's Most Dangerous Eating Disorder, external

"She left us a very detailed note and she felt there was no hope for her, that there was nothing in place to help people with her condition," her mum Lesley tells Newsbeat.

"In the absence of the help she needed, she couldn't see any way of carrying on."

Type 1 diabetes is an irreversible autoimmune disease which requires constant care.

People with type 1 diabetes don't produce insulin and they need it to stay alive.

Every time they eat carbohydrates they must inject insulin.

They must check their blood sugar levels frequently.

Diabulimia refers to diabetic people who deliberately take too little insulin in order to lose weight.

Doing this can be incredibly dangerous.

"That's Megan," says her mum Lesley. "That's how I'll remember her"

"The one thing that not taking your insulin does, is you lose weight - you have an ideal tool," explains Lesley.

She says that "Megan sometimes looked a bit thin but there was never anything that would indicate anything extreme".

Experts say there are potentially thousands like Megan who are seemingly living a "normal" life but hiding their illness.

The leading type 1 diabetes charity JDRF estimates 60,000 15 to 30-year-olds are living with T1 in the UK.

Lesley, Megan's mum, says "she hid a great deal from us, we had no idea she was not taking her insulin"

Professor Khalida Ismail is lead psychiatrist for diabetes at King's Health Partners, London.

She runs the only outpatient clinic in the UK specifically for people with diabulimia.

"You can look quite well and have a normal body size," she tells Newsbeat.

"And yet because you're restricting insulin, you are running very high blood sugars and you are increasing your risk of diabetes complications."

She explains that this can include damage to the eyes, kidneys and nerve endings.

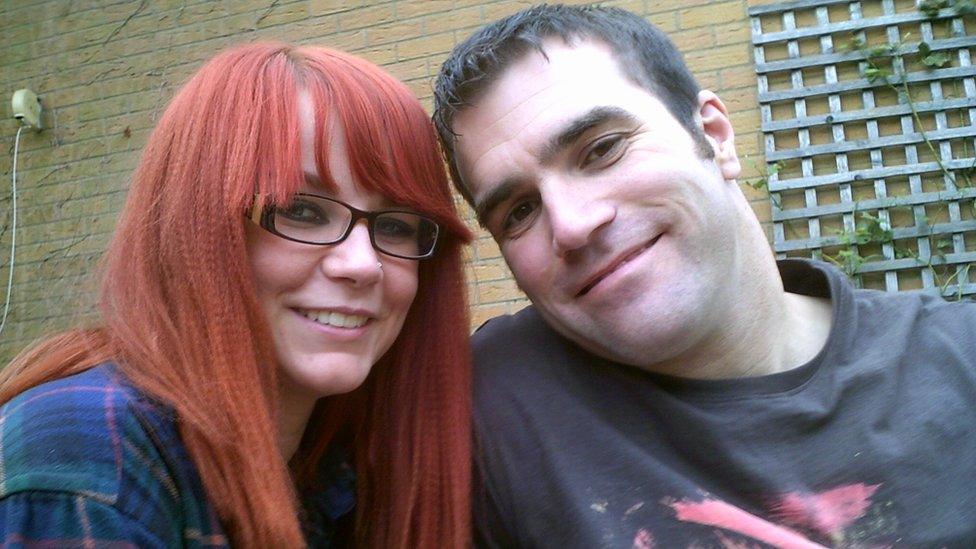

After Megan's death her family found there was an "inner circle" who knew more about her illness, including three friends and her boyfriend of six years.

"Like the loyal boyfriend, I was sworn to secrecy," Andy tells Newsbeat.

In her suicide note Megan asked Andy to become an "honorary Davison"

Olivia Davison says her older sister was, "immense, because she was just Megan"

In her note Megan talks of her treatment in an eating disorder inpatient unit.

She describes managing her own insulin because "not one member of staff on the ward was even trained to administer insulin let alone understand it".

"They gave me back my insulin because they couldn't figure out the doses.

"It's the equivalent of giving an alcoholic vodka or giving a bulimic a bottle of laxatives."

This picture appeared on Megan's funeral order of service - she loved elephants

Her parents want Megan's story to be known to help other families.

"The information they're getting is just wrong for them," says Lesley.

"It might be the best that's available for the moment but it isn't anywhere near good enough."

She adds that Megan "needed something that was specific" to the condition and "not a sort of ad hoc of pieces that didn't really do the job".

DWED, external (Diabetics With Eating Disorders) campaigns for the omission of insulin for weight loss to be recognised as a mental illness.

Founder Jacqueline Allan says diabulimia is still not viewed in the right way.

"The second you stop taking your insulin you're in the same amount of danger, regardless of your weight."

Prof Ismail agrees and says psychiatrists need to "wake up" to diabulimia.

"The condition is very hidden," she says. "Diabetes teams don't know how to talk to patients about it.

"Eating disorder teams only see the extreme cases."

She wants diabulimia to be recognised formally.

"Once psychiatrists start talking about it, debating it, awareness will grow."

Megan's dad Neal says they knew so little they would have been in "no-man's land" without the letter.

"I honestly don't know how we would have coped with it."

"She didn't want us upset," adds Lesley. "And yet you end up devastated because nobody has been able to help her."

Tim Kendall, NHS England's national clinical director for mental health, tells Newsbeat that "people are waking up to it".

"I was involved in producing the NICE guidelines on eating disorders and we devoted a whole section on how you manage people who've got diabetes and an eating disorder.

"We're now disseminating that around the country. We have been asleep, no doubt, but we are waking up."

NHS England says it's integrating psychological services with physical health, including placing 3,000 new mental health therapists in GP practices.

For more information on diabulimia you can look at these information and support pages.

Find us on Instagram at BBCNewsbeat, external and follow us on Snapchat, search for bbc_newsbeat, external