Coral bleaching in Fiji: How the country is protecting its vital reef

- Published

- comments

WATCH: What is coral bleaching?

In February, Newsround went to Fiji to find out how climate change is impacting its beautiful coral reef. The country is home to the most extensive coral reef in the South Pacific Ocean but warming seas have previously caused devastating coral bleaching which has a huge impact on the local communities and wildlife which rely on it.

Stressful events caused by climate change - like storms, cyclones, floods, and warming seas - have a harmful impact on coral and are happening with increasing frequency and intensity across the world.

Acidification is another impact of climate change on our oceans. This is when the chemistry of the ocean changes, which affects the process by which corals build their skeleton.

Read on to discover how local communities and scientists in Fiji are working together to help their reef recover.

Corals are a group of living animals related to sea anemones and jellyfish which build hard skeletons and grow on the ocean floor.

Reef-building corals live in shallow, warm, tropical seas and form a very important relationship with plant-like algae that live inside them.

The algae are the main way the coral gets energy to survive and grow, and the algae also gives the coral a lot of its colour. Reef-building corals are effectively solar-powered animals.

Why are coral reefs important?

Coral reefs are an important underwater ecosystem, often called the 'rainforests of the ocean'. Check out this colourful coral reef in the Namena Marine Reserve in Fiji

Coral reefs are hugely important for lots of reasons:

Covering less than 0.1% of the seabed, coral reefs are home to 25% of the world's marine species.

Corals attract fish which provides food for local communities. Without the reef, the food security for island communities is at risk.

Island communities rely on the reef for income from fishing.

The reef is a big tourist attraction which provides jobs. The reef is the backbone of island economy.

Their large structures protect the coastline from erosion.

And corals and other organisms living on coral reefs can even be used to make medicines.

What causes coral bleaching?

WATCH: Coral reef expert, Victor Bonito, tells Newsround how ocean acidification harms coral reefs

Coral bleaching is a stress response that happens when the sea becomes too cold or too hot or when pollution or freshwater enters the sea. The relationship between the coral and the algae breaks down and the coral pushes out the algae. Without the algae, the coral loses it major source of food and turns white. If corals remain bleached for too long then they can die.

As well as climate change stresses, the El Nino event also impacts coral. This is a climate cycle that occurs every 2 to 7 years and causes sea temperatures to increase in certain parts of the world.

With bleaching now taking place about once every six years on average, corals often don't have enough time to recover before the next event.

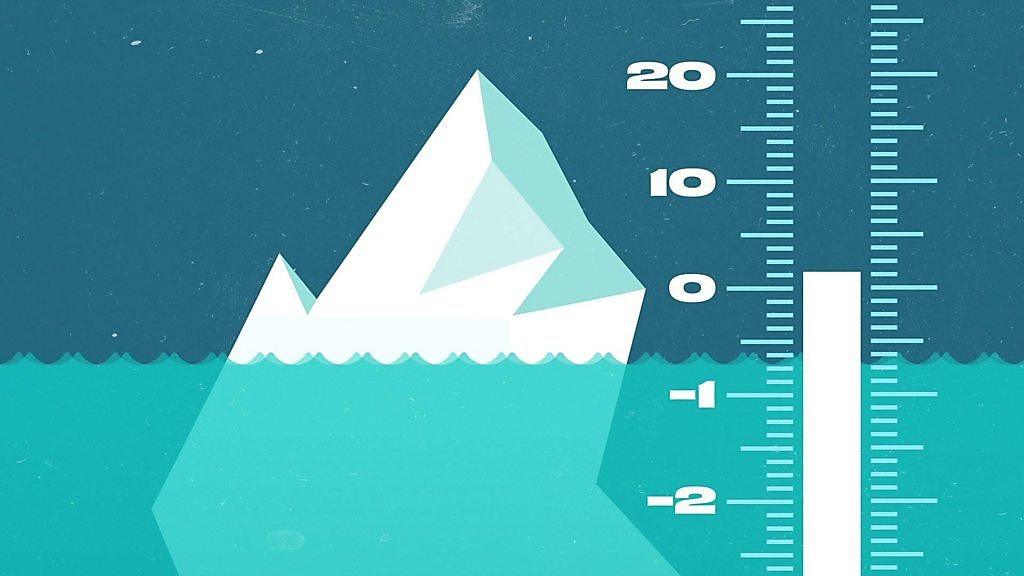

According to a 2018 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), ocean warming, acidification and more intense storms will cause coral reefs to decline by 70 to 90 percent, if there is a 1.5C warming of the atmosphere. It is predicted that if the planet warmed by 2C, coral reefs would completely disappear.

This loss of corals would dramatically decrease biodiversity in countries like Fiji and directly impact about a half billion people worldwide who depend on coral reefs.

What's the situation in Fiji?

This image, taken during Fiji's 2016 bleaching event, shows the impact warming seas have - turning once colourful corals white

Climate change and human-caused problems like over-fishing and pollution are putting Fiji's reefs at risk.

In 2000, the country suffered a severe bleaching event and since then has experienced at least three other events, the last major one being in 2016 which saw 30 - 60% of the coral killed in shallow reefs along the Coral Coast.

This extensive bleaching event had a big impact on coastal wildlife and killed thousands of fish.

But the community is fighting back.

How is the community protecting the reef?

Victor Bonito, coral reef expert, checking on his heat-tolerant coral nursery

Newsround spoke to Victor Bonito, a coral reef scientist, who has been working in Fiji for 15 years.

He has been working closely with the community to restore coral reefs.

In response to the devastating bleaching event in 2000, Fiji established no-take Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) which limited fishing and other activities in areas. This work also engaged the young people from coastal villages in marine ecotourism and conservation.

10 years after the MPAs were introduced, coral cover had increased by 500% and there were 50% more coral species than in the neighbouring fished areas which hadn't become a protected area.

Heat-tolerant coral is grown on rope, breeze blocks and metal grids before being transplanted onto the ocean floor

Bonito also started identifying types of corals that didn't bleach as badly and were able to cope better with heat. He now grows more than 7000 heat-tolerant corals a year in five nurseries along the coast.

This work has helped to restore coral cover and increased a healthy fish population. Reports from January 2020 showed that coral communities in protected areas affected by the 2016 bleaching have nearly recovered to pre-bleaching levels.

Whilst the protected areas have been a success, some communities in Fiji still haven't recovered from previous bleaching. Parts of the reef that are outside of these protected zones are still suffering with low coral cover due to overfishing.

'We really need global action to address this'

WATCH: Victor Bonito gives his tips on how you can help protect coral reefs

Growing heat-tolerant coral on the reef has given many people hope that it can recover from future bleaching events.

However, if the stress on the coral lasts for too long, or if the rate of change in the temperature or chemistry of the ocean is too fast, then it will become much more difficult for coral to survive.

When asked about the success of his heat-tolerant coral, Bonito told Newsround that, "coral restoration is not a solution to climate change."

"We can try to select heat-tolerant corals and multiply them, but there is a limit to that. We can't replant an entire reef. Coral restoration on its own won't be enough."

"Unless we address the underlying problem that's causing climate change, we're not going to stand much of a chance of saving our coral reefs."

- Published19 September 2020

- Published13 September 2020

- Published14 September 2020

- Published28 April 2020