Aurora borealis: How northern lights are created has now been discovered

- Published

- comments

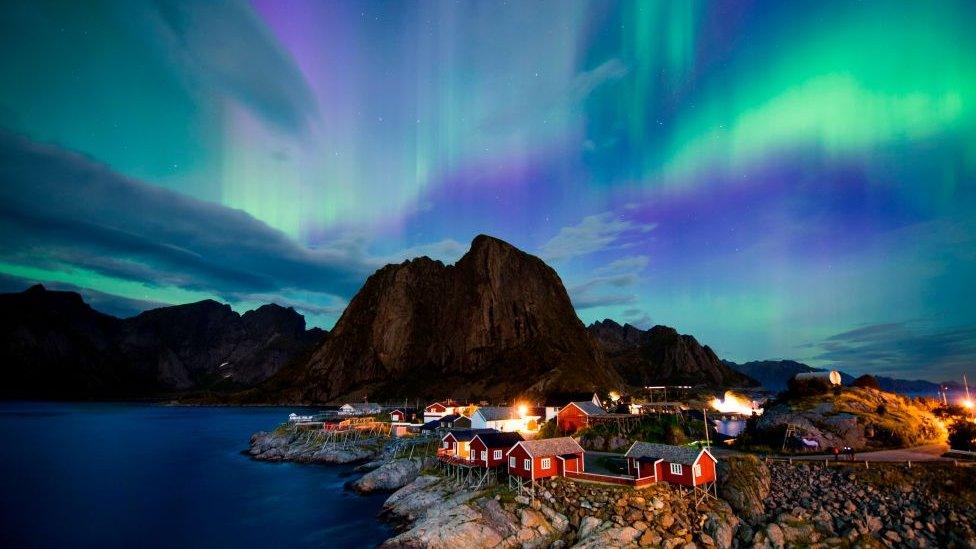

The aurora borealis, or northern lights, is a spectacular natural light display.

The phenomenon appears as shimmering waves of light in the sky but scientists have never been able to prove how they are created.

Well researchers at the University of Iowa have now found that the most brilliant auroras are made by powerful electromagnetic waves during geomagnetic storms....wow.

Let's find out more...

How are they created?

The study found that electromagnetic waves, also known as Alfven waves, accelerate electrons towards Earth, which cause the particles to produce the light display we call the northern lights.

"Measurements revealed this small population of electrons undergoes 'resonant acceleration' by the Alfven wave's electric field, similar to a surfer catching a wave and being continually accelerated as the surfer moves along with the wave," said Greg Howes associate professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Iowa.

The northern lights are caused by the interaction of the solar wind - a stream of charged particles escaping the Sun - and our planet's magnetic field and atmosphere.

Scientists were able to confirm what they found by recreating what happens in a lab at the Large Plasma Device at the University of California, Los Angles (UCLA).

They used a 20m long chamber to recreate the Earth's magnetic field.

"Using a specially designed antenna, we launched Alfven waves down the machine, much like shaking a garden hose up and down quickly, and watching the wave travel along the hose," said Howes.

The experiment didn't recreate the colourful lights but they found from their calculations they could prove that "electrons surfing on Alfven waves can accelerate the electrons that cause the aurora" added Howes.

Aurora borealis: Amazing Northern Lights display in Finland

Scientists from across the US were pleased to hear the news.

Patrick Koehn, at Nasa said: "I was tremendously excited! It is a very rare thing to see a laboratory experiment that validates a theory or model concerning the space environment."

He added: "It does help us understand space weather better. It will be of use in space weather forecasting as well, something that NASA is very interested in."

- Published9 June 2021

- Published10 June 2021

- Published9 June 2021