Malaria: Children across Africa to get 'historic' vaccine

- Published

- comments

Children across much of Africa are to be vaccinated against malaria in what experts are calling a 'historic moment' in the fight against the deadly disease.

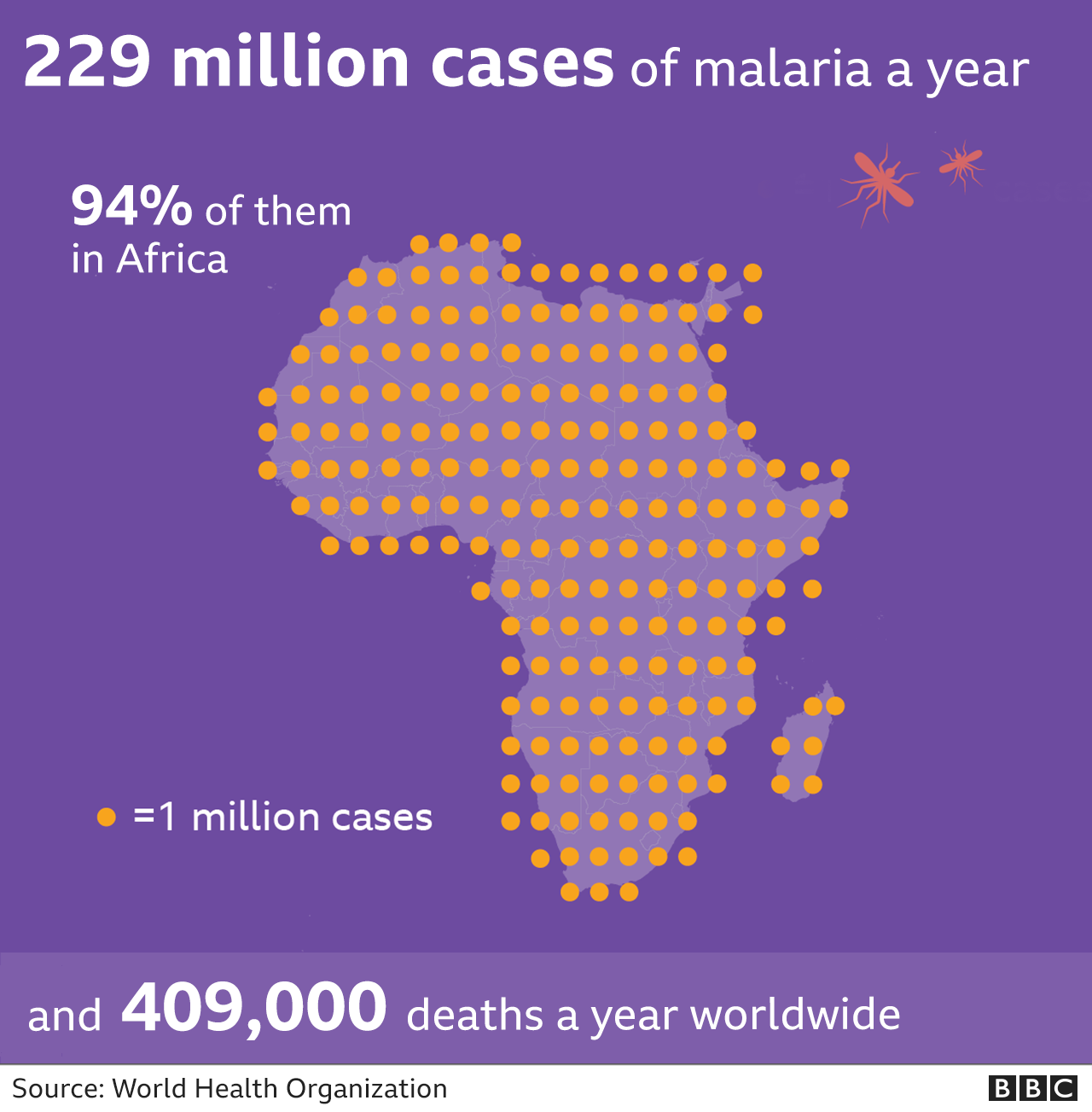

Malaria is a deadly disease carried by mosquitoes which affects hundreds of millions of people every year.

It is mainly found in Africa and Asia, as well as Central and South America.

Having a vaccine - after more than a century of trying - is being hailed as among medicine's greatest achievements.

The vaccine called RTS,S was proven effective six years ago, but more testing still needed to be carried out.

Now after pilot programmes in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi, the World Health Organization says the vaccine should be rolled out across sub-Saharan Africa and in other regions that have moderate to high malaria transmission.

Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, director-general of the WHO, said it was "a historic moment".

"The long-awaited malaria vaccine for children is a breakthrough for science, child health and malaria control," he said. "[It] could save tens of thousands of young lives each year."

What is Malaria?

Malaria is a parasite that invades and destroys our blood cells in order to reproduce.

It's spread by the bite of mosquitoes.

Drugs to kill the parasite, bed-nets to prevent bites and insecticides to kill the mosquito have all helped reduce malaria.

But the heaviest toll of the disease is felt in Africa, where more than 260,000 children died from the disease in 2019.

It takes years of being repeatedly infected to build up immunity and even this only reduces the chances of becoming severely ill.

Dr Kwame Amponsa-Achiano piloted the vaccine in Ghana to assess whether mass vaccination was a good idea and would be effective.

"It is quite an exciting moment for us, with large scale vaccination I believe the malaria toll will be reduced to the barest minimum," he said.

Constantly catching malaria as a child inspired Dr Amponsa-Achiano to become a doctor in Ghana.

"It was distressing, almost every week you were out of school, malaria has taken a toll on us for a long time," he told me.

Saving children's lives

There are more than 100 types of malaria parasite. The RTS,S vaccine targets the one that is most deadly and most common in Africa: Plasmodium falciparum.

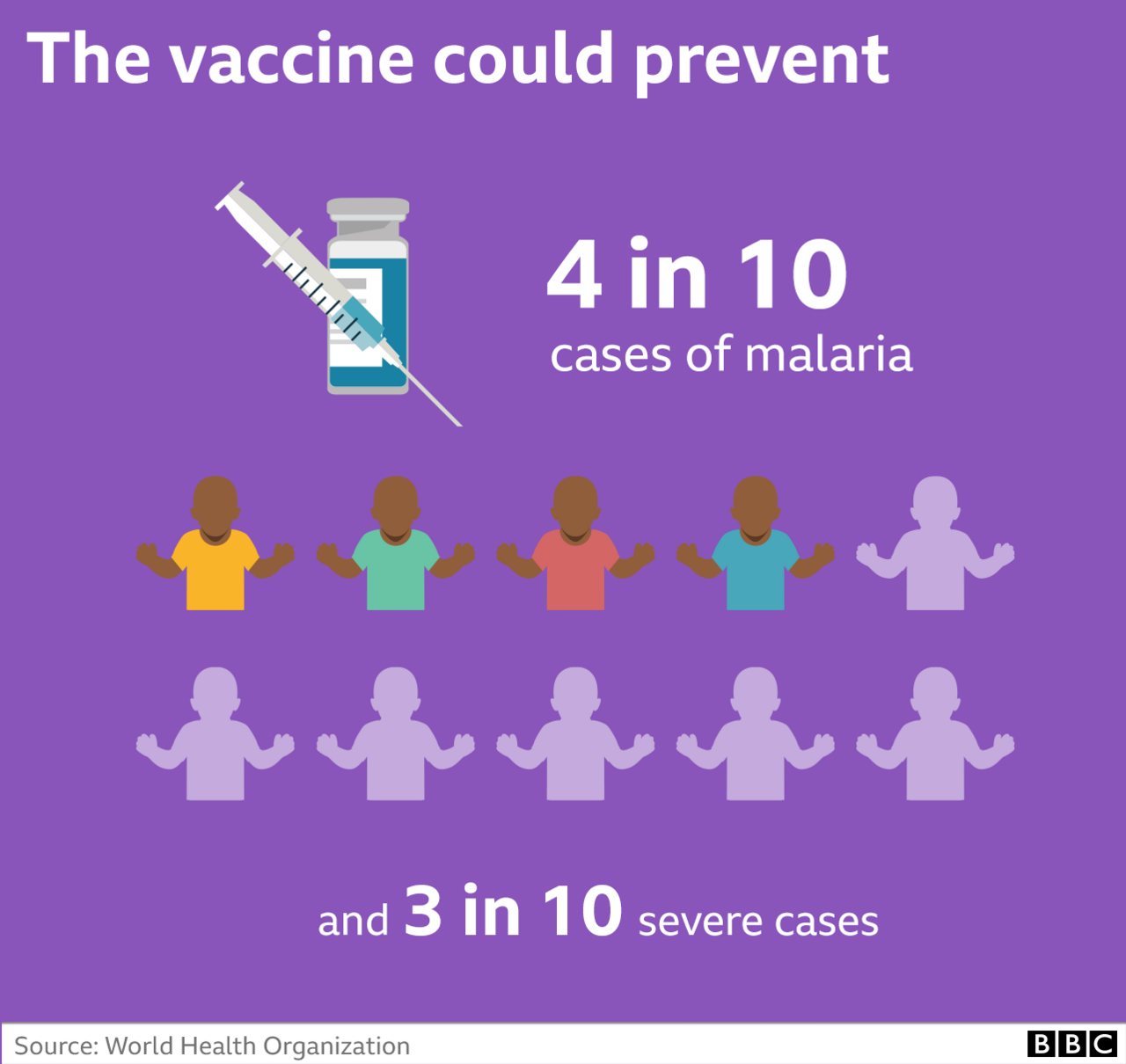

Trials, reported in 2015, showed the vaccine could prevent around four in 10 cases of malaria, and three in 10 severe cases.

It could also reduce the number of children needing blood transfusions by a third.

However, there were doubts the vaccine would work in the real world as it requires four doses to be effective.

The first three are given a month apart at five, six and seven months old, and a final booster is needed at around 18 months.

Dr Pedro Alonso, the director of the WHO Global Malaria Programme said: "From a scientific perspective, this is a massive breakthrough, from a public health perspective this is a historical feat.

"We've been looking for a malaria vaccine for over 100 years now, it will save lives and prevent disease in African children."

Why is malaria so hard to beat?

Football star David Beckham is a high profile campaiger aiming to raise awarenss of malaria

Having just seen the world develop Covid vaccines in record time, you might be wondering why it has taken so long with malaria.

Experts say that the parasite that cause malaria is far more complex and sophisticated than the virus that causes Covid.

The malaria parasite has evolved to avoid detection by our immune system. That's why you have to catch malaria time and time again before starting to get even limited protection.

Leah explains the big step made in the fight against malaria

It has a complicated life cycle across two species (humans and mosquitoes), and even inside our body it morphs between different forms as it infects liver cells and red blood cells.

Developing a malaria vaccine is like nailing jelly to a wall and RTS,S is only able to target the malaria in the stage between being bitten by a mosquito and the parasite getting to the liver.

It is why the vaccine is 'only' 40% effective. However, this is still a remarkable success and paves the way for the development of yet more vaccines.

- Published23 April 2021

- Published25 April 2024

- Published3 December 2020