Ivory poaching: Why many elephants in Mozambique don't have tusks

- Published

- comments

Normally both male and female African elephants have tusks, which are really a pair of massive teeth.

But a new study suggests there is a serious reason for why lots of tuskless elephants can now be found in the country of Mozambique in Africa - poaching.

During a civil war in the country, that lasted from 1977 to 1992, up to 90% of Mozambique's elephant population was killed, mainly for their ivory tusks.

Elephants without tusks were normally left alone by hunters, so this made it more likely they would breed and pass on the tuskless trait to their children.

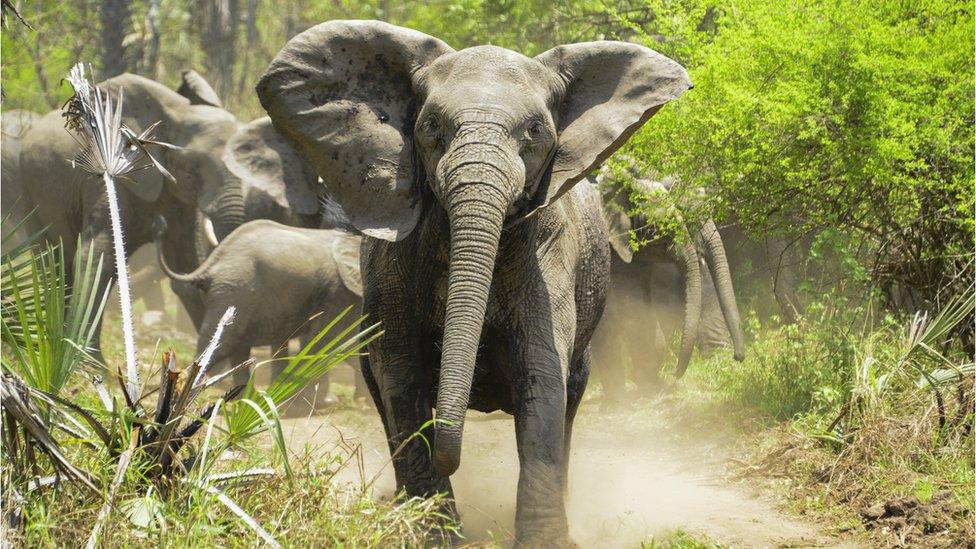

Despite their lack of tusks, it's often the females who can be seen defending the herd

What did the study discover?

Before the civil war, about 18.5% of females were naturally tuskless, but that figure has risen to 33% among elephants born since the early 1990s.

Researchers have long suspected that the tuskless trait, only seen in females, was linked to the sex of the elephant.

As in eye colour and blood type in humans, genes are responsible for whether elephants inherit tusks from their parents.

During the civil war between 1977 to 1992, poachers sold the ivory to finance the conflict, including buying arms and ammunition.

This pushed the species to the brink of extinction.

Jenny finds out about the struggle facing Africa's elephants - and what's being done to stop it

Back in 1969 Gorongosa National Park was home to over 2200 elephants, but now there is just over 700 in the park.

Professor Robert Pringle of Princeton University said: "Tusklessness might be advantageous during a war, but that comes at a cost."

Another potential knock-on is changes to the broader landscape, as the study has revealed that tusked and tuskless animals eat different plants.

What can be done to help save the elephants?

Professor Pringle said it was possible to reverse this trait over time as long as work to recover elephant populations from the brink of extinction continues.

He said: "We actually expect that this syndrome will decrease in frequency in our study population, provided that the conservation picture continues to stay as positive as it has been recently.

"There's such a blizzard of depressing news about biodiversity and humans in the environment and I think it's important to emphasise that there are some bright spots in that picture."

- Published12 August 2023

- Published5 October 2016

- Published22 January 2021