SHSAT exams: Children want equality in New York City schools

- Published

- comments

Newsround's Kizzy Cox explains why young people in New York think schooling in the city is unfair

More than a year after the Black Lives Matter protests in America, young people in New York are still campaigning for racial justice - this time at the city's top schools.

A youth-led movement called Teens Take Charge says the school system in New York treats black and Latino children unfairly and wants that to change.

Gabrielle, a Teens Take Charge member, goes to a specialised school in the city, she says she's lucky because the opportunities aren't equal for children living in different neighbourhoods: "Why do we not get an equal education just across the entire city?"

This year, the number of black and Latino students accepted into New York's specialised schools has fallen to the lowest level in three years.

These high schools are some of the best in New York City and receive millions of dollars in extra funding, but figures show that black and Latino students are much less likely to get in, compared to white or Asian children.

A history of school segregation in New York

As a city, New York is constantly changing, its skyline - full of giant skyscrapers - looks dramatically different compared to 50 years ago.

But one thing that campaigners argue hasn't changed much in all that time, is New York's public schools, which remain some of the most segregated in the country.

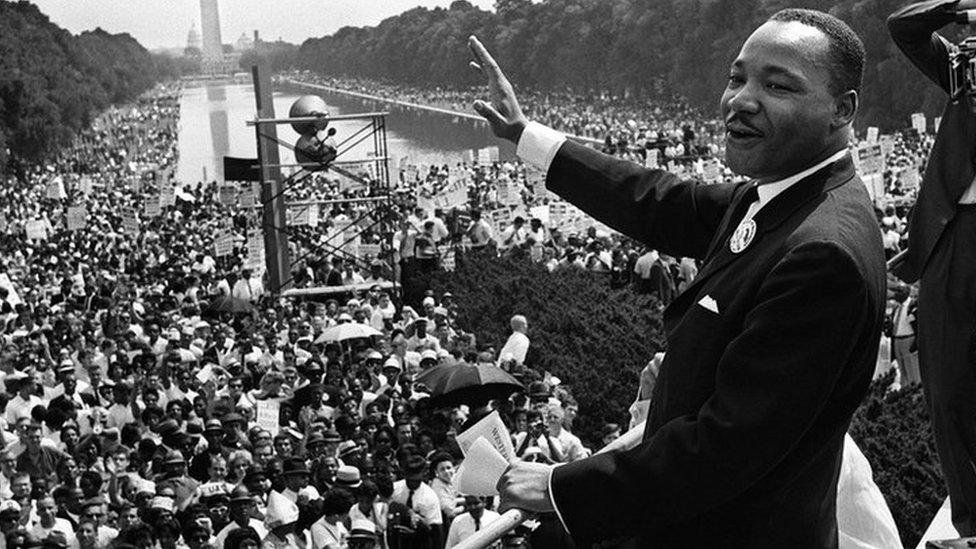

New York has a long history of racial inequality in schools and in 1964 a protest about schooling in the city became one of the largest civil rights demonstrations of all time.

In what is known as the New York City school boycott, or Freedom Day, nearly half of all New York City school children deliberately missed lessons to demonstrate against segregation and unfairness in the city's public school system.

The protest involved nearly half a million people - as kids were joined by their parents and teachers to protest.

Racial segregation means keeping black, white and people of different races apart. Until the 1964 Civil Rights Act in the US, black and white people were not allowed to use the same shops, toilets, buses, parks and schools.

But in reality, even after the Civil Rights Act, segregation continued in schools in places like New York City, because neighbourhoods had already been separated into different groups.

School segregation - separating children of different races at school - had officially become illegal in New York City from 1920, but in reality black and white children still went to different schools and had different opportunities.

That was because banks refused to give money to black families to buy houses and those who had money couldn't buy homes in white areas. It meant neighbourhoods were separated into groups of different races as a result.

White kids would go to mostly white schools. Meanwhile, schools that had mostly black and Latino students had poorer facilities, less experienced teachers and were overcrowded.

Five months on from the school boycott protest the Civil Rights Act became law in the United States. It was a huge historical moment for the country and meant it was illegal to discriminate against someone based on their race, colour, religion, gender, or where they came from.

But even after the Civil Rights Act, school segregation continued in US cities including New York.

Today, 57 years later, the city continues to have some of the most segregated schools in America.

Gabrielle from Teens Take Charge says it's time things in New York changed: "When they're like your local public school is going to be bad [because of where you live] and the neighbourhood over from yours, with a whole bunch of wealthy white kids, is going to be good and those are the rules...

"I think we've done a great job of questioning; 'why is that?'"

So why are there fewer black and Latino children at New York's top schools in 2021?

This year New York City's specialised high schools have had even fewer black and Latino students accepted compared to other recent years, and the numbers were already low.

Places for these children have dropped to 9% in 2021 compared to 11% last year and 10.5% in 2019.

To get into the schools, children have to pass something called a Specialised High Schools Admissions Test, or SHSAT for short.

The US Department of Education says the drop in numbers of black and Latino children getting accepted is because fewer students took the SHSAT tests as a result of the pandemic.

This year, 23,500 8th graders - aged 13 and 14 - took the test in January, compared to 27,500 last year.

But some people say the exams discriminate against children from black and Latino backgrounds because they aren't able to get a good enough education to pass the test in the first place.

Is the SHSAT the problem?

Stuyvesant, a specialist school in NYC, has only eight black students in a class of 749

At one top high school in the city called Stuyvesant, a class of 749 has only eight black students, that's despite nearly a quarter of all school children in New York city being black.

At Brooklyn Technical, the country's biggest high school, out of 1,607 places, 64 black students and 76 Latino students were accepted compared to 844 Asian students and 499 white students.

"You get a lot of amazing opportunities that you are able to do and I'm so thankful for that," says Gabrielle.

"I've been able to find a great community within my school especially among the black students, I've been able to push myself to new limits and find new things to take over and challenge within the school."

Like her friends, Gabrielle had to take the Specialised High School Admissions Test to get in. But she doesn't think future students should have to.

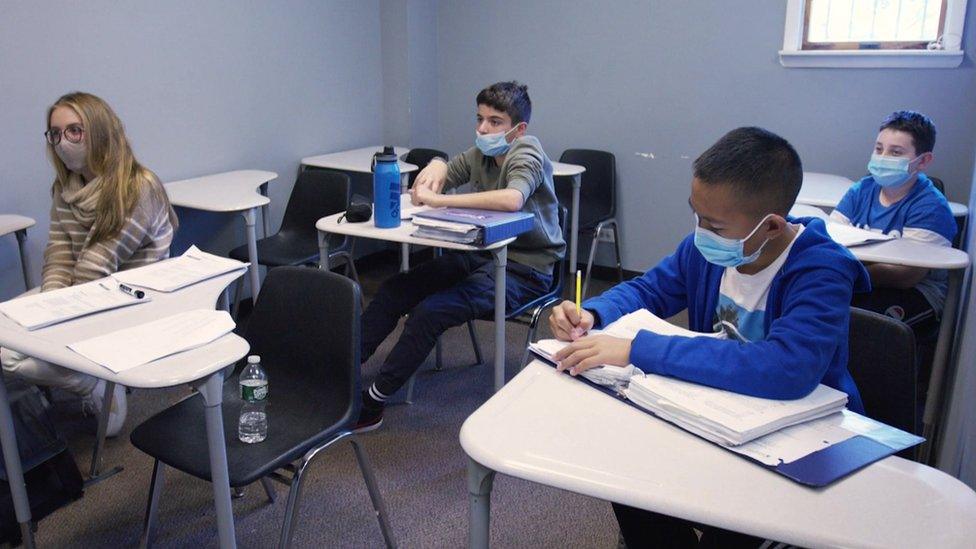

For families who can afford to, many children take extra tuition to try and pass the Specialised High Schools Admissions Test

Studying for the exam can involve hours of extra work and for children who want to get a place, it can mean their parents paying thousands of dollars for tuition.

For some black and Latino communities in New York City, parents are in low-paid jobs and that makes it hard to afford extra help for their kids. Without the extra help it makes passing the SHSAT exam much harder.

There are cheaper alternatives however, but they often result in crowded classrooms and a lack of resources to help kids reach the level they need to get to - especially when many from disadvantaged communities are behind with their education already.

"When you have a lot of students that you jam-pack into a room and half of them are on a standard 7th grade level and barely know 7th grade curriculum, it's about catching them up for [regular] high school, it's not about getting them into specialised high schools," says Gabrielle.

She attended a $600 course with other black and Latino children to prepare for the SHSAT exam. While she was there she studied in an over crowded class with more than 45 other students.

So what needs to change?

Teens Take Charge say schools need to be better so that every child has an equal chance in New York City.

They think that getting rid of the SHSAT exam, which only benefits a small proportion of New York's children, is the first step.

New York's new mayor-elect Eric Adams, only the second black mayor in NYC history, also wants more black and Latino kids to have the chance of getting into specialised schools.

To do that, he agrees schools across the city need to improve, but he has no plans to get rid of the SHSAT exam.

New York's new mayor, Eric Adams starts the job in January 2022

Meanwhile, the Chinese American organisation CACAGNY (Chinese American Citizens Alliance of Greater NY) has taken the city's current mayor to court saying getting rid of the test would unfairly discriminate against New York's Asian children.

The Asian community in New York accounts for six out of every ten kids who get into specialised high school in the city.

They say the test doesn't discriminate against different races and allows children, especially those whose first language isn't English, to be successful.

"If you try to change it... this test that is blind to all these things that a person cannot control, that hurts children [and their opportunities]," says Wai Wah Chin, charter president of CACAGNY.

Why do they get a better education than me because they are wealthy and white? Why do they get a better education than me simply because I exist in a separate area?

Despite being one of the lucky ones who made it to a specialised school in the city, Gabrielle says she will continue to campaign for other kids in the black and Latino communities to get an equal chance, no matter where they live.

"That fight within our generation has made it so we are able to promote a lot of these changes.

"Why do they get a better education than me because they are wealthy and white? Why do they get a better education than me simply because I exist in a separate area?"

- Published9 June 2020

- Published2 June 2015

- Published20 January 2021