Northern Ireland: 50 years since Bloody Sunday

- Published

- comments

On Sunday 30 January 1972 - 50 years ago - a devastating event happened in Londonderry, sometimes called Derry, in Northern Ireland.

It happened during a civil rights demonstration, at a time when the conflict in Northern Ireland had been getting worse.

Soldiers, who were part of the British Army's Parachute Regiment, shot at the protestors killing 13 people and wounding 15 others.

The day became known as Bloody Sunday, and is often regarded as one of the darkest days of the Northern Ireland Troubles.

What were the Troubles?

The conflict in Northern Ireland dates back to when it became separated from the rest of Ireland in the early 1920s.

Great Britain and Ireland had been one country, but it split from British rule - leaving Northern Ireland as part of the UK, and what is now the Republic of Ireland as a separate country.

How was Northern Ireland created 100 years ago?

There had long been different views and sometimes tension between unionists and nationalists, the two main communities in Northern Ireland.

Unionists were mostly Protestant, and Nationalists were mostly Catholic.

Unionists, who were happy to remain part of the UK - some of them were also called Loyalists (as they were loyal to the British crown)

Nationalists, who wanted Northern Ireland to leave the UK and join the Republic of Ireland - some of them were also called Republicans (as they wanted Northern Ireland to join the Republic of Ireland).

During the 1960s, the tension between the two sides turned violent, resulting in a period known as the Troubles.

Many people were killed in the fighting.

Why did Bloody Sunday happen?

Protesters regularly took to the streets to call for civil rights in the late 1960s and 70s

In the run up to these events there had been an increase in violence and bombings in Northern Ireland.

The government decided the only way it could restore order was to bring in a new law which meant the police and other authorities could imprison people without trial.

This was called internment, and many people were unhappy about this. They said it was unfair and a step too far.

Thousands gathered in Derry on Sunday 30 January for a rally organised by the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association to protest against internment.

British soldiers and members of the press are pictured behind armoured water cannon and armoured cars during a civil rights march in Derry

But the Northern Ireland government had banned such protests, arguing that it would keep things calm.

At that time the army had been sent to Northern Ireland to help the police, and soldiers were in Derry for the march.

But after clashes between groups of youths and the army, soldiers from the Parachute Regiment moved in to make arrests.

Stones were thrown and at first the soldiers fired with rubber bullets, tear gas and used a water cannon.

Two men were shot and wounded. Not long after the soldiers began to open fire using live ammunition.

What happened after the events of Blood Sunday?

While unionists spoke of their regret at the numbers of deaths in Derry, some said that the Civil Rights march had been illegal and so should not have taken place at all.

In the nationalist community people were very angry about what had happened.

Support for the Irish Republican paramilitary group, the Provisional IRA, grew in the nationalist community, particularly in Derry.

This is a group with weapons, not formed legally by the government but simply by people joining together.

A wreath of remembrance is laid at the memorial to those killed on Bloody Sunday

People weren't just upset in Northern Ireland.

In Dublin, the capital of the Republic of Ireland, the British Embassy was burned by a crowd of protestors.

In Boston in the United States, the large Irish community there held a Catholic mass to remember those killed.

Crowd at St. James the Major church in Boston on 6 Feb 1972 for a memorial Mass

The British government later set up an inquiry with a judge appointed to look more closely into the events of Bloody Sunday.

What did the first inquiry say?

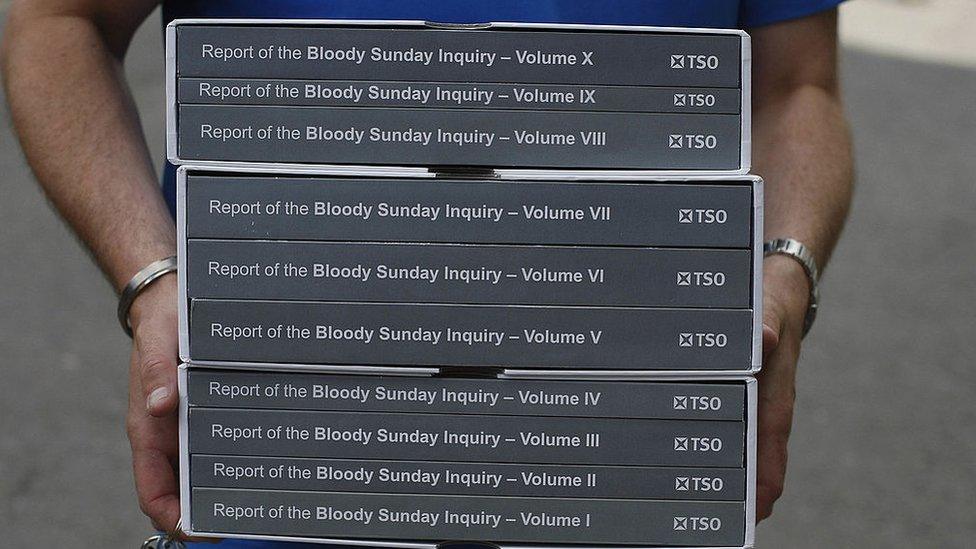

The first investigation was led by Lord Widgery, the most senior British judge.

He concluded that the soldiers were fired on first and the victims had been handling weapons.

Lord Widgery decided that the army had not been to blame for what had happened, and largely cleared the soldiers.

Relatives of those who died on Bloody Sunday were far from happy with the first inquiry and campaigned for years for the evidenve to be looked at again

However he described the soldiers' shooting as "bordering on the reckless".

The victims families were very angry at this result calling it a "whitewash", and spent years campaigning for a fresh public inquiry to challenge it.

What the second inquiry say?

This picture shows the Good Friday Agreement being signed by two politicians - the British Prime Minister Tony Blair (on the left) and the Irish Prime Minister Bertie Ahern

On 10 April 1998, something called the Good Friday Agreement (or Belfast Agreement) was signed to bring peace to Northern Ireland.

Shortly after this, the then Prime Minister Tony Blair announced that a new inquiry would be held, because of "the weight of new material available".

The Saville Inquiry became the longest-running inquiry in British legal history and cost about £200m.

It found that none of the people killed had been posing a threat or doing anything that would justify them being shot. It also said that no warning had been given before the soldiers opened fire.

Lord Saville found that some of the soldiers had been shot at - but not by those who were killed.

Derry's Guildhall Square was packed for David Cameron's apology on behalf of the state in 2010

He said that on balance, the Army had fired first.

David Cameron - who was prime minister when the report was released - apologised, and said the killings were "unjustified and unjustifiable".

What is Northern Ireland like now?

Two children from Belfast - Ryan and Kirsty - hear from their teacher what life in Northern Ireland used to be like (March 2017)

Northern Ireland now is a very different place to the past.

The Good Friday Agreement agreement helped to bring to an end much of the conflict, although there have still been some instances of violence since then.

Last year marked 100 years since the creation of Northern Ireland which is an anniversary which is seen in very different ways by different sections of the community.

The nationalist community do not want Northern Ireland to be governed as part of the UK and would like to see the island of Ireland being all one country which governs itself.

But the unionist community strongly believe that Northern Ireland has a British identity and should remain part of the UK.

As such, there are always differences of opinion on lots of aspects of life in Northern Ireland.

Police officers were attacked during the protests in Belfast in 2021

Last year, there was some street violence for a few days in some areas, which was linked to changes which have come into force following Brexit.

Many unionists are unhappy that the Brexit deal has created different trade rules for Northern Ireland from the rest of the UK, because they say it undermines their British identify.

- Published3 May 2021

- Published10 January 2020

- Published12 May 2020

- Published1 March 2017