Greenland Ice Sheet is cracking quicker than scientists predicted

- Published

The world's second biggest body of ice - the Greenland Ice Sheet - is cracking open quicker than scientists had previously thought.

That's according to new research by a team of scientists, led by Dr Tom Chudley, from Durham University's Geography Department.

The team of researchers studied more than 8,000 3D maps of the Arctic ice-sheet's surface, made up of high-quality satellite pictures.

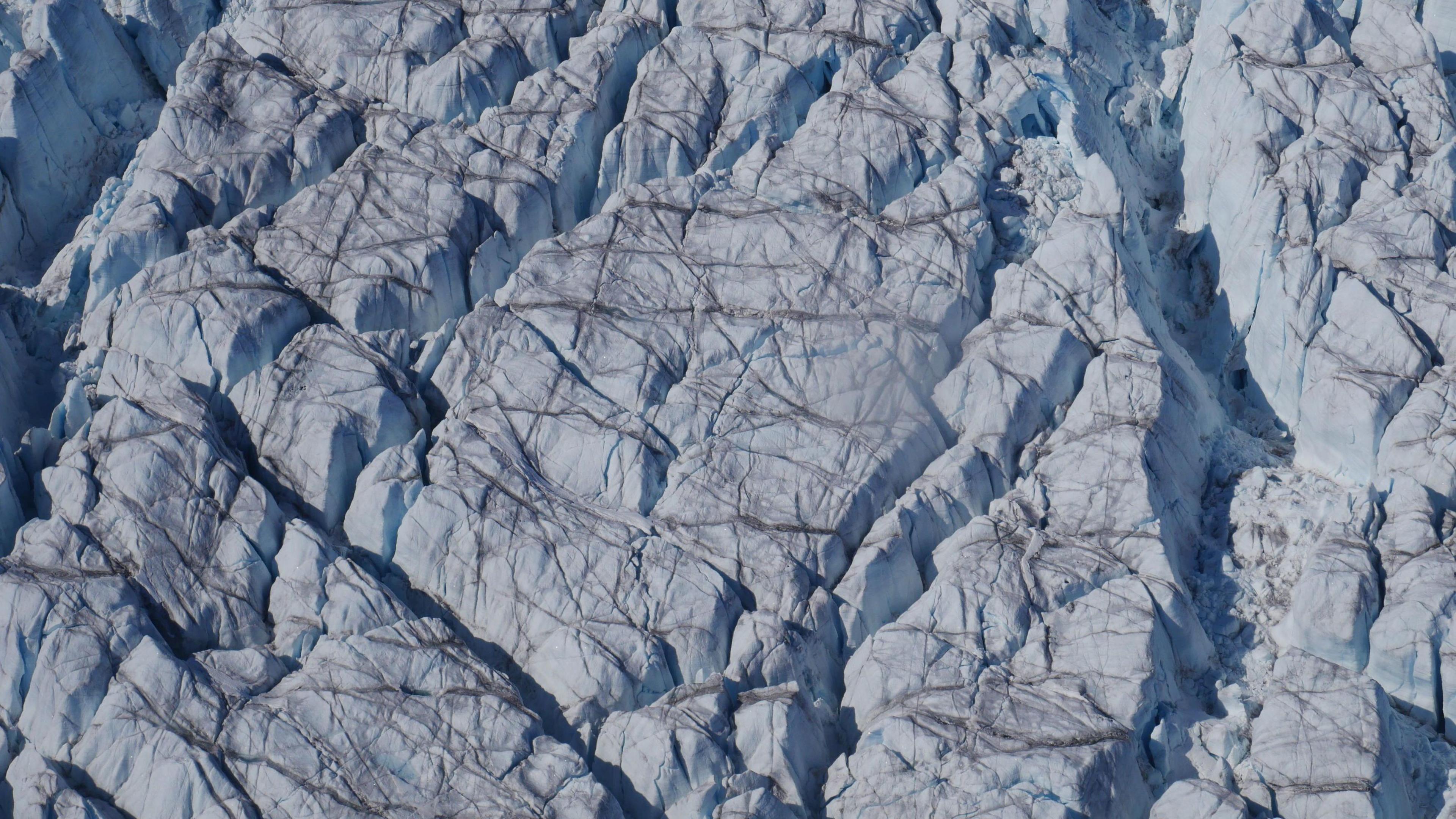

From this they found that crevasses - or cracks - in the ice, had significantly increased in size and depth near the edges of the ice sheet between 2016 and 2021.

Climate change: What is it?

- Published20 January 2020

Why scientists are worried about Greenland's future

- Published18 September 2019

Climate change: Ice melting at 'worst-case' rate

- Published3 September 2020

What is the Greenland Ice Sheet?

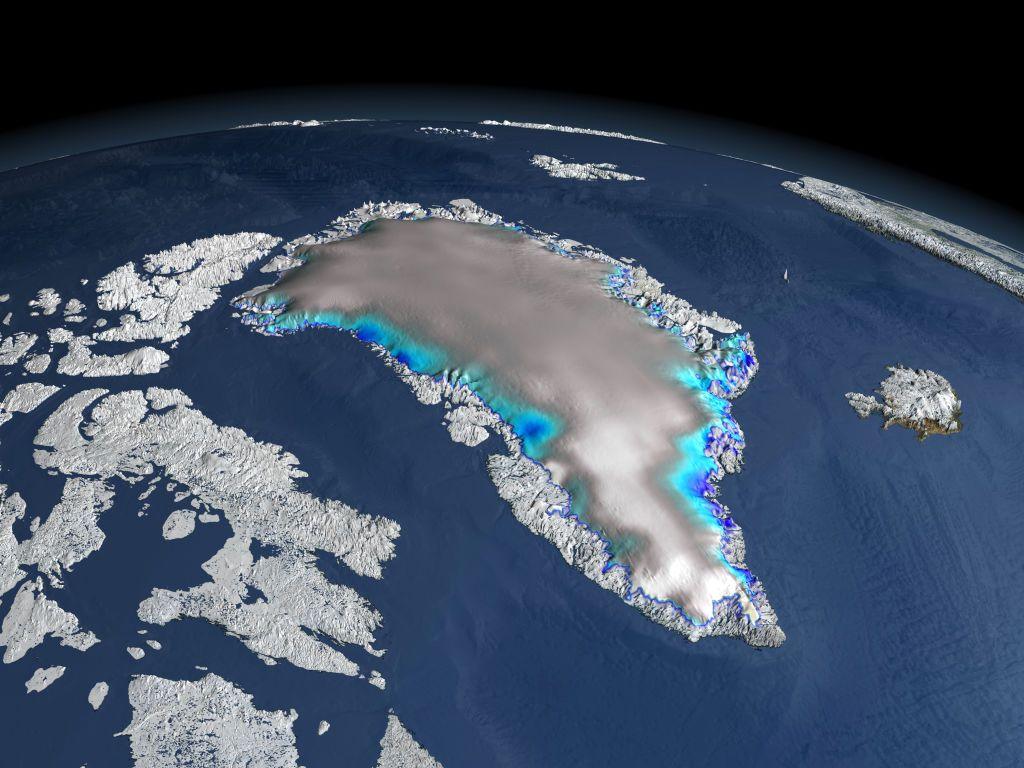

The Greenland Ice Sheet is a glacier that covers 80% of the island of Greenland.

Greenland is the world's largest single island.

It is really close to the North Pole, and most of the island is part of the Arctic circle - so it's very, very cold there.

An illustration of the Greenland Ice Sheet, which covers most of the island of Greenland - taken from satellite data

The researchers say that the crevasses are getting bigger and deeper where ice is flowing more quickly due to climate change, and that this could speed up the loss of ice from Greenland.

Since 1992 scientists have noted the loss of ice on Greenland has been behind a sea level rise of around 14mm.

If the whole Greenland Ice Sheet was to melt, sea levels around the world could rise by seven metres, the scientists say.

"In a warming world, we would expect to see more crevasses forming." said Dr Tom Chudley, the lead author of the study.

"This is because glaciers are accelerating in response to warmer ocean temperatures, and because meltwater filling crevasses can force fractures deeper into the ice." he said.

If the entire Greenland Ice Sheet was to melt, scientists think that sea levels could rise by around seven metres.

"However, until now we haven't had the data to show where and how fast this is happening across the entirety of the Greenland Ice Sheet.

"For the first time, we are able to see significant increases in the size and depth of crevasses at fast-flowing glaciers at the edges of the Greenland Ice Sheet, on timescales of five years and less," said Dr Chudley.

The researchers hope their findings will allow more scientists to help predict the future behaviour of the Greenland Ice Sheet.