Climate change: 'Losing Greenland' is a worry for scientists as temperatures rise

- Published

- comments

The effects of climate change and increasing temperatures are causing problems across the world.

But in Greenland in particular, researchers say they're "astounded" by the rate at which the glaciers and ice sheets are melting.

During this year alone the island lost enough ice to raise the average global sea level by more than a millimetre.

Scientists are very concerned about what this will mean for the future of cities on coasts around the world.

Initially the changes will be very small but experts warn that in the decades to come, as the planet heats up, more ice will melt causing serious consequences.

For low-lying countries like Bangladesh, even a small rise in sea level can pose a real danger, with huge areas of the land being lost to the sea.

If the ice starts melting even faster, higher areas of land - for example Florida - may also be at risk over the next century.

But in the worst case scenario, parts of Eastern England and dozens of cities around the world could actually go underwater unless new defences are built to protect them.

BBC science editor David Shukman visited the Sermilik glacier in southern Greenland back in 2004. He has now returned to the same spot, to find that the glacier has thinned by 100m in 15 years.

The glacier has more than halved in thickness, exposing the remaining ice to the warmer temperatures of lower altitudes.

Scientists have also warned that Greenland's massive ice sheet may have melted by a record amount just this year.

Where is Greenland?

Greenland is part of the Arctic, and is the world's largest island.

There are approximately 56,500 people living there (many of Inuit descent), making it the least densely populated country in the world.

By comparison, the UK has 67.5 million people, even though it's around nine times smaller in terms of land mass.

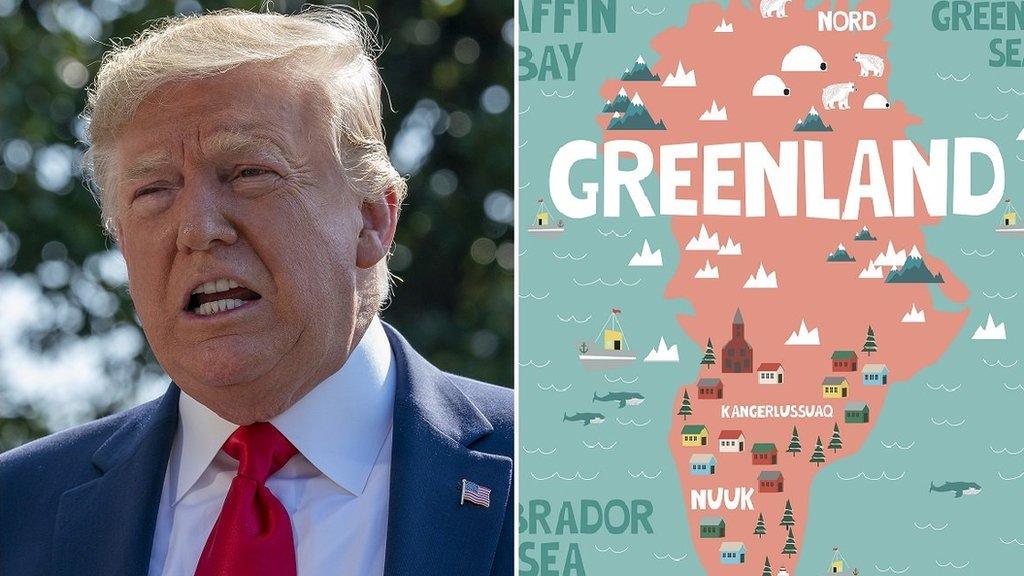

The island has been in the news recently because US President Donald Trump said he wanted to buy Greenland.

The President's state visit to the island was cancelled after the prime minister of Denmark - who own Greenland - said it wasn't for sale.

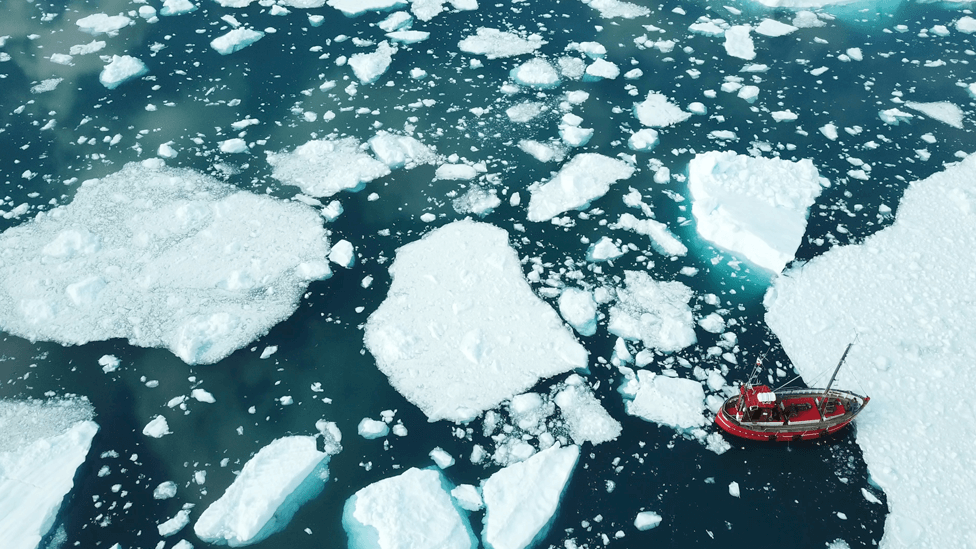

Icebergs can be seen floating at the mouth of the Ilulissat Icefjord from the town centre

One of the main reasons why so few people live there is because around 80% of its surface is covered in ice.

In fact it's the largest mass of ice in the northern hemisphere, covering an area of around seven times the size of the United Kingdom and reaching up to 3km (2 miles) in thickness.

The reason why the ice melting is so worrying is because of the very important role it plays in the global climate system.

Why does melting ice in Greenland matter?

The giant ice sheet reflects so much of the sun's energy back into space, that it helps to control sea temperatures through what is known as the "albedo effect".

Because of where the ice sheet is in the North Atlantic, its melt-water also influences the water moves around in the ocean.

But Greenland is especially vulnerable to climate change, as Arctic air temperatures are currently rising at twice the global average rate.

Because of the amount of ice on the island, the average sea level would rise around the world by about seven metres, if it all melted.

The BBC science editor David Shukman's says: "No one is suggesting that could happen for hundreds or even thousands of years, but even a small increase in the rate of melting in coming decades could threaten millions of people living in low-lying areas."

What do young people in Greenland think about climate change?

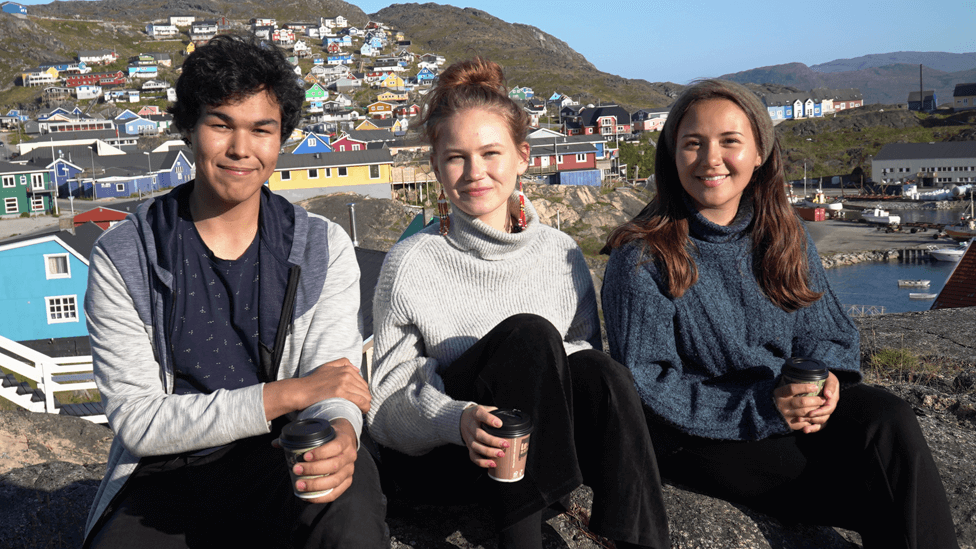

Inutsiaq Ibsen, 18, Naja-Theresia Høegh, 19, and Caroline Hartmann Hansen, 21, in Qaqortoq

For some young Greenlanders, climate change is becoming a big concern, partly because of the impact of 'their' ice on other areas of the planet.

Naja-Theresia Høegh, who has just finished school, was inspired by the Swedish campaigner Greta Thunberg to lead a climate strike in her town of Qaqortoq.

She describes a boat trip to the edge of the ice sheet where she found it "astonishing and scary" that so much water could flow out.

"All of that is ending up in our waters, into the sea, and to the rest of the world and, if this continues, it will someday just cover a whole country."

Her friend Caroline Hartmann Hansen also talked about her fears over the melting.

"It's not our fault - it's everyone's," she said.

- Published21 August 2019

- Published21 August 2019