Ben Johnson: Doping's reluctant poster boy wants soul set free

- Published

I would beat Bolt - Johnson

Twenty-five years ago Ben Johnson's mum told him to "tell the truth and set your soul free". Johnson told the truth but his soul remains trapped, tormented and desperately searching for the way to catharsis. But Johnson has spied an opening.

Sport's most famous drug cheat - cyclist Lance Armstrong might argue the toss, or maybe not - is now an anti-doping crusader. Touring the globe calling for the war on drugs to be more potent, seeking reconciliation, asking for forgiveness.

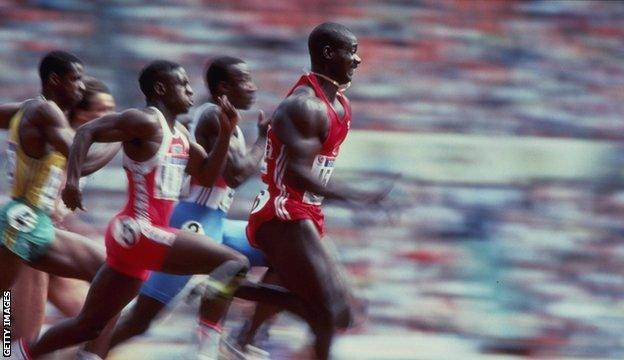

To Johnson's opponents it was all about those bloodshot eyes: intimidatory, predatory, at least when he deigned to look at them.

The eyes remain bloodshot but now they are wary, haunted, so that you wonder why he has agreed to open himself up like this, to this queue of journalists doubling as mechanics, looking to prod and yank under the bonnet and find out the truth.

Until you remember that this could be the way out for his trapped and tormented soul, however painful the process might be.

Six of the eight athletes from the 100m final at the Seoul Olympics have been associated with drugs

"People always say 'time will heal all wounds'," the Canadian, now 51, tells BBC Sport. "But I don't believe in that. It heals to a certain point but it's always in the back of your head: 'This is what I did.'"

There was a time, not too long ago, when the 10-second barrier in the men's 100m was just that - to be dipped under, maybe broken, but a barrier nonetheless. Until Johnson, whose winning performance at the 1988 Olympics, external was one of sport's genuine gobsmacking moments. "9.79 seconds! How did he do that?!" Drugs, as it turned out.

Asked immediately after his victory what meant more to him, his new world record or his gold medal, Johnson was unequivocal: "The gold medal - that's something no-one can take away from you." Only they did. And then some.

Johnson has been the poster boy for doping ever since, although he believes he should be sharing top billing.

Of the eight athletes who competed in that 100m final in Seoul, six have been associated with drugs. Johnson's great rival Carl Lewis,, external whom it was later revealed tested positive in the US Olympic trials but was exonerated by the US Olympic Committee, was upgraded to gold. Britain's Linford Christie, external was found guilty of using the performance-enhancing drug nandrolone in 1999.

"When I first got into track I thought people just trained hard, got good coaches and got good results," says Johnson.

"But my coach [Charlie Francis] said to me: 'This is what your competitors are doing, for you to compete you have to do this and that.' I made the wrong choice, became the best and lost it all.

"I see myself as a victim in certain ways. I don't want my name being called out every time someone tests positive. That's not fair. Why am I singled out as the biggest cheater in sport?"

Perhaps because, having finally told the truth at the Dubin Inquiry in 1989,, external Johnson failed drug tests again in 1993 and 1999.

In an attempt to redress the situation, Johnson has joined forces with Jaimie Fuller, the Australian sportswear entrepreneur who has campaigned to topple Pat McQuaid as president of the UCI,, external cycling's world governing body.

Fuller, who is not paying Johnson to lead his #ChooseTheRightTrack, external campaign, is keen that I portray the former sprinter as repentant. Which, for the most part, he seems to be. At least to the extent I feel sympathy towards him, bordering on pity.

Perhaps those who declared their hatred for Armstrong in the wake of the seven-time Tour de France winner's admission of drug-taking will find their emotions become similarly recalibrated with time. Perhaps they will realise it is possible to feel sympathy for a man without being an apologist for his behaviour.

At a track meeting in Toronto in June, where Johnson competed in a pro-am relay, he beamed as he posed for pictures flanked by delighted kids. The same might happen to Armstrong one day.

Like Armstrong, Johnson convinced himself he wasn't cheating because he believed almost everyone else he was competing against was doing the same. But the only time during our chat that Johnson betrays a sense of irritation is when he is compared to the fallen American. Armstrong, Johnson clearly believes, is a badder man than him.

"My situation is a little bit different to Lance's," says Johnson, who was reduced to racing horses and stock cars and coaching the son of Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi following his fall from grace.

"I treat people with respect and class, through good times and bad times. Lance called people names, bullied people. If he had been nice to people during his cycling career he wouldn't be in such a bad situation right now.

"But cycling needs to work with him. It's the right thing to do, to teach the younger generation not to dope, to try to make sure what happened 25 years ago doesn't happen again. They need to be told that there are no excuses left - they ran out.

"But what this campaign is also about is us saying: 'We're here to support you.' There is no rehabilitation for these young kids who go wrong, they're left alone."

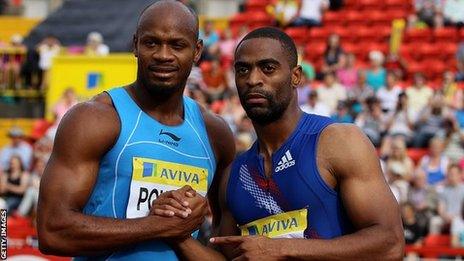

Usain Bolt is the world record holder, but Johnson says he would have beaten him in his prime

Given the recent drug busts of former world champion Tyson Gay and former world record holder Asafa Powell, Johnson is rather more pessimistic about the present, which he believes is even dirtier than his day.

"Most of the people who watch track and field know what's going on," says Johnson. "No athlete is going to say they're dirty if they're top of the world."

It is a measure of how far to the peripheries of his sport Johnson has drifted that when Fuller initially attempted to track him down, the Canadian athletics federation had no idea of his whereabouts.

But he was out there, coaching in Ontario, dabbling in reality TV, spending time with his eight-year-old granddaughter. Not watching Usain Bolt.

"I don't watch too much track and field," says Johnson, who believes he would have beaten Bolt in his prime, despite the Jamaican's 100m world record standing at 9.58 seconds.

"It just so happens that every time Usain Bolt is running I'm picking my granddaughter up from somewhere."

Would Johnson like his granddaughter to become an athlete like him? "For a hobby, yes. As a professional, no. She'll go to school, get her education, get married, have kids and live a clean life. Anything can happen in track and field."

On 24 September, the 25th anniversary of the race dubbed the "dirtiest in history",, external Johnson will return to that stadium in Seoul and present his anti-doping petition. Seeking reconciliation, asking for forgiveness.

Because anything can happen in track and field, which is why only those with the hardest hearts would resent seeing Johnson's soul set free.

- Published15 July 2013

- Published15 July 2013

- Published18 August 2013

- Published29 August 2013

- Published10 September 2015

- Published8 February 2019