Isobel Pooley: GB high jumper on the body beautiful & raising the bar

- Published

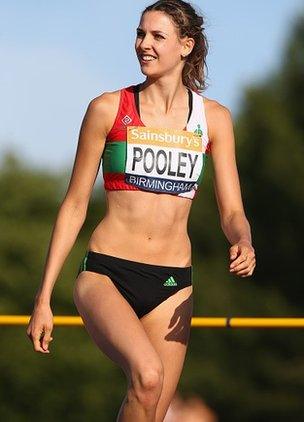

Pooley jumped 1.97m at the British Championships in Birmingham

Here's a tall story - an ultra-fit champion British athlete who suffers jibes every day because of her body.

High jumper Isobel Pooley is not overweight, but stands 1.92m (6ft 3½in), and some people cannot get their heads round that height.

"People swear and say: 'She's huge, have you seen that girl over there?' And I want to turn round and say: 'I'm not deaf,'" she tells BBC Sport.

"It's a part of my daily life. They say: 'How tall are you?' or just make pointless comments that don't go anywhere like 'You're really tall aren't you?' 'Aren't you tall?' 'You're massive'.

"People are just so rude without realising. They assume that it's OK to point it out. It's not kind ever to stop and stare at people, but that's what us tall people have to endure."

The 22-year-old is certainly using her height to her advantage though, setting a British record, qualifying for next month's World Championships, and eyeing a shot at the 2016 Olympics.

She opens up to BBC Sport about the psychology of the high jump, why Serena Williams is a 'goddess in her body' and how sport has helped her overcome prejudice.

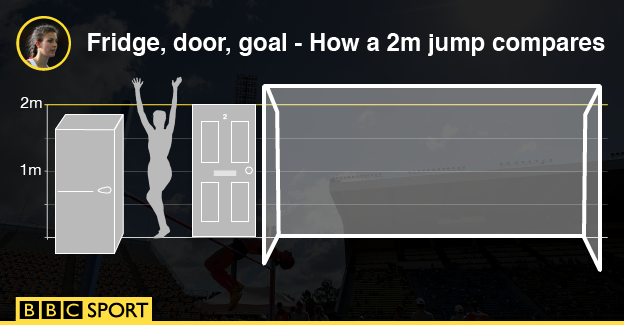

Higher than a fridge - the two-metre test

There's an old athletics adage that you're not a "proper" high jumper until you soar past your own height.

London-born Pooley was raised in Hampshire, studied in Nottingham and trains in Loughborough

Pooley went five centimetres clear of that when setting a new GB outdoor record of 1.97m at the British Championships earlier this month, and had the chance to go for a milestone.

"Two metres is the landmark height for a lot of female jumpers. To attempt that at a British Championships in front of a home crowd was absolutely sensational. It was such a monumental experience," she recalls.

"Despite not being successful at the attempt, I was able to at least look up to that bar and square up to it and feel confident in the near future that I am actually going to be able to tackle that height."

Her successful jump of 1.97 matched heptathlete Katarina Johnson-Thompson's indoor mark at Birmingham earlier in the year.

Only three women in the world have gone higher in 2015., external It was the latest stage in the progression of Pooley, who set the previous best British mark of 1.96 in Germany last year, passing a 33-year-old record, and was third in a Diamond League event in Doha in May.

"I'm ready and I gave myself a strong and consistent message in the weeks leading up to the British trials that I was going to be able to give that outstanding performance," she said.

"The feeling landing on the bed and knowing I was over the bar was just immense gratification, and feeling that's no less than I deserve because I've worked really hard and the only thing I've changed is I've let myself believe I can jump that high."

Flawed fixation - missing out on London 2012

"High jump is hugely psychological. The bar is a challenge and it is inevitably going to catch you out in the end - it always ends in a failure," says Pooley.

Despite only being 19 at the time, Pooley nearly reached the qualifying standard for the 2012 London Olympics.

But at 1.90m, just two centimetres short of the standard needed to make a home Games, she froze.

"I got so fixated on the height of the bar, and about achieving selection, I was just incapable of jumping or even attempting that bar to anything near my ability," she adds.

"I actually knew how to clear it, I had the answers, but I was so flustered about the concept of this home Games. The temptation when the bar goes higher is to change things, and that inevitably ends in disaster."

Pooley won silver in the 2014 Commonwealth Games in Glasgow, her first major senior medal

Pooley started to fulfil her potential at senior level with a silver medal at last year's Commonwealth Games in Glasgow.

"There are indicators of potential such as my height, dedication to training, the fact my coach (Fayyaz 'Fuzz' Ahmed), external bothers with me at all - his time is like gold dust - and he devotes so many hours to training me shows I must be worth it," she says. "All I want to do is live up to how good I can be and the bar is an irrelevance now."

Mind games - 'don't try, just achieve it'

Pooley went to London as a spectator, cheered on training partner Robbie Grabarz to Olympic bronze, and now regards missing out as a blessing in disguise, having learned to trust her own techniques and believe in herself.

"A lot of the problems us high jumpers encounter are created in our own head as a reaction to the height of the bar. If we don't know the height, it makes it a lot more simple," she says.

"In training, my coach will put the bar up and not tell us how high it is so a lot of the time we are in the dark."

To get her approach right, Pooley has been helped by psychologists, including Julie Crane - the wife of her coach Ahmed - who herself won high jump silver for Wales, external at the 2006 Commonwealth Games.

Crane uses neuro linguistic programming,, external which examines how your thinking can affect performance.

"She'll pick up on things I have said which have significance that I didn't realise," says Pooley. "So I'll say something like 'I'm going to try to achieve this' and she says 'No, don't try, just achieve it'."

How it all started |

|---|

Aged 13, and already 6ft tall, she tried high jump for the first time in a school PE lesson. |

"I liked the fact it was individual, it wasn't a team sport and I wasn't going to let anyone else down or rely on anyone else. I didn't have to do ball skills. I just had to run and jump, and that seemed very attractive in its simplicity. |

"The moment I tried it, I thought 'this is the best thing ever'. When I had the chance to go down to my local club I jumped - excuse the pun - at the opportunity." |

'Why does the man have to be the big guy?'

Pooley believes athletes have a kind of inner beauty, harnessed through ability.

"For me it's not about looking thin, it's about jumping high," she says.

"If I reach the point where I'm super light and unhealthy, that's not a positive situation to be in. It's about being the best athlete I can be.

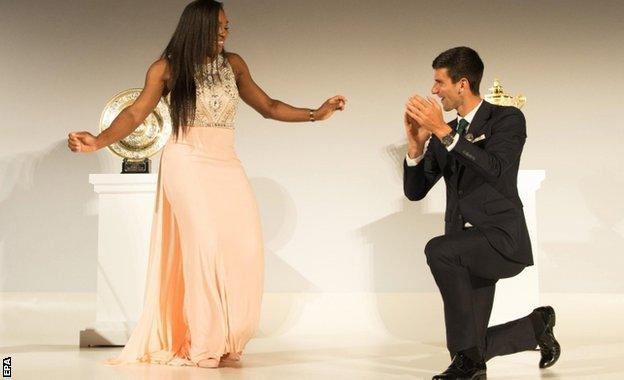

Wimbledon winners Serena Williams and Novak Djokovic at the tournament's Champions Dinner

"I enjoyed watching Serena Williams in the tennis, because she is a goddess in her body. She is big compared to your average woman, but nobody would say she is not beautiful.

"Her beauty is practical too, where you are not judging it on what it looks like but what it can do, and I think that's a really healthy principle to take into wider society.

"I hate it when people say: 'How are you ever going to find a boyfriend?' assuming that he has to be taller. Why do we have to think the man has to be the big guy? There are big women and small men."

'I would have killed to be 5ft 3in'

Pooley is tall even for a high jumper, towering over most opponents, and has learned to love her height. It means she takes fewer strides, for example.

Pooley made the front cover of Athletics Weekly after her British title

"Luckily I'm confident in my skin now but when you are growing up, especially when you are in your teens, that is an incredibly difficult time for any young person in terms of their own body image and self confidence," she says.

"Sport helps so much because all of a sudden it threw a positive light as it was such a clear advantage to be tall.

"When I was growing up, I would have killed to be 5ft 3in, instead of 6ft 3in, but now I wouldn't give up my height for the world.

"I'm glad life threw me that challenge because it has helped me become a lot more confident in a whole multitude of ways."

Whereas many people are reluctant to comment on weight, race or disability, height seems to be fair game - footballer Peter Crouch endured chants of "freak" earlier in his career.

"Sport is fantastic for flipping those nasty comments on their head," adds Pooley.

"A fundamental philosophy of being an athlete is 'control the controllables' and if you can't change something all you can change is your attitude towards it.

"When people say to my mum: 'Oh you're daughter's awfully tall,' she replies: 'Yes, and she's British champion in the high jump.'"

New rivals - and new heights on the horizon

Training features surprisingly little jumping - maybe 10-20 efforts in three sessions a week - alongside co-ordination drills, weights, short sprints and acceleration runs.

"It is a really common misconception that we just jump all the time but that is just not physically possible, our bodies would break down," she says.

Pooley largely trains with men for whom 2m is no big deal, but now has company in Victoria Dronsfield, the Sweden-born high jumper with an English father who has just been accepted as a British athlete.

"She pushes me on a daily and weekly basis. Although the boys push me, it's almost a bit too extreme to try and lift their weights or run as quickly as they do; having a female makes it that more attainable as a goal."

What's the high jump like? |

|---|

"To take off is quite difficult, tons of bodyweight goes through one leg so you have to get the right speed and the right angle. |

"It's almost exactly like riding a motorbike round a corner - when you lean into the curve, you have to have a certain amount of speed to stay on your wheels, but equally too much and you'll crash. |

"A good run-up will usually produce a good jump. Sometimes you can know three or four strides away from the bar, because you know how a good jump feels in training. |

"It's very immersive when you do get it right. You're concentrating so hard it is almost like you're not doing anything. I wouldn't say that I am completely there in a conscious sense. Your body does the hard work, and your brain enjoys the ride." |

Becoming Britain's first female Olympic high jump medallist might seem a tall order - but don't rule out GB's rising star from reaching new heights.

She has another Diamond League meeting in Monaco on Friday, but there will be no appearance in the Anniversary Games in London, external a week later.

"Unfortunately they've chosen not to put a women's high jump in the programme, which is very disappointing but I'm going to do my utmost on the Friday night to come down and watch Robbie [Grabarz]," she said.

After her World Championships debut next month - "Beijing is going to be a hell of a big deal" - attention will switch to next year's Olympics, and then the 2017 Worlds in London.

"It's completely realistic that I can make the Beijing final, and then to be an Olympic finalist at 23 would be an enormous landmark for me," she adds.

"It's really easy to get ahead of yourself when you give one good performance but this is going to be a long journey and 2017 is a massive target. Having a home World Champs is an opportunity that many athletes would give their right arm for."

- Published14 July 2015

- Published10 July 2015

- Published10 September 2015

- Published8 February 2019