Greg Rutherford: World triumph proves Briton is worthy champion

- Published

- comments

Rutherford secures golden grand slam

World Athletics Championships |

|---|

Venue: Beijing National Stadium, China Dates: 22-30 August |

Coverage: Live on BBC TV, Red Button, Radio 5 live, online, mobiles, tablets and app. Click here for full details. |

What makes a champion?

Not just inherited physical talent, although Greg Rutherford has that: a great-grandfather who played football for Arsenal and England.

Not merely dedication, although Rutherford moved to another continent to train with his coach and then, when he returned to the UK, built a long jump pit and runway in his own back garden so he could train at any time and on any day.

It can't be financial support, because this is a man who lost his kit sponsor a few months after winning Olympic gold and responded by setting up his own clothing line to both wear and pay his mortgage.

Determination? Certainly it helps, for many would give in or try something less capricious, having torn a hamstring at one previous World Championships and limped out injured of another.

All those things, in different ratios, can take you to a major final. But what decides your fate when the battle begins is a recipe more subtle and scarce: fortitude under immense pressure, calmness in the storm, finding your very best when excuses are everywhere to come up just short.

This was a world long jump competition that no-one could get right.

Rutherford's winning jump of 8.41m was the second furthest of his career - his best is 8.51

The USA's Jeff Henderson came into the night having jumped far further than anyone else this year. He was out after the first three jumps, fouling twice and coming up short in the other.

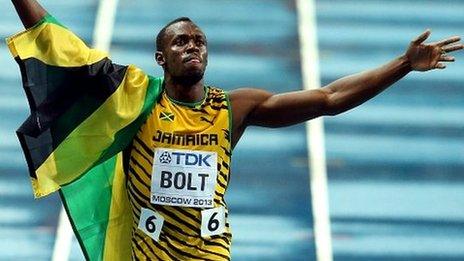

Defending champion Aleksandr Menkov, strong enough to succeed with home support two years ago in Moscow, could manage only 8.02 for sixth on distant soil.

Another American, Mike Hartfield, failed to register a single mark. His much-vaunted team-mate, Marquis Dendy, failed to even get through qualifying.

You could find legitimate reasons everywhere. The runway in the Bird's Nest appears unfeasibly fast, the athletes disconcerted by its pace and the way the take-off board seemed to be upon them a foot sooner than normal.

A wide-open final brought its own strange pressures. The three Chinese contenders, Jianan Wang, Xinglong Gao and Jinzhe Li, found the deafening home support not just a wind at their backs but a gale, with jump after jump blowing past the board.

In a blizzard of no-jumps and red crosses on the scoreboard, Rutherford, too, wavered. His first-round jump was huge but so was the foul. So ill had he felt earlier in the day that he doubted if he could even compete. Get-out clauses everywhere. Great effort, better luck next time.

Jeff Henderson, world number one coming into Beijing, had set a world-leading 8.52m in July

Alone among his rivals, he found not just explanations and excuses but solutions. Back came the throttle. Out went his second effort, safely on the board, for 8.29m. More pressure on those rivals. More over-striding. Less control.

In the fourth round, Rutherford went further still: 8.41m would not just be enough to win it, it was the second longest jump of his life.

Rutherford's winning jumps | |

|---|---|

8.31m - 2012 Olympic Games | 8.29m - 2014 European Championships |

8.20m - 2014 Commonwealth Games | 8.41m - 2015 World Championships |

After his Olympic triumph in 2012, Rutherford was derided in some quarters as lucky. The big names had messed up. He was competing in an era that paled in comparison to even the recent past.

When he added the Commonwealth title last summer, it attracted the usual asterisk: it's only the Commonwealths. When he won European gold a few weeks later, the critiques shifted only slightly: wait until you're up against the real big boys.

Maybe now, after completing the grand slam of major titles in three years, having beaten everyone there is to beat, on different days, on different tracks, in different conditions, the equivocating will come to an end.

Some might still point dismissively at the distances he has jumped, in an event where the championship record is 8.95m. Rutherford's winning mark in London of 8.31m was the shortest to take Olympic gold since 1972.

All three of Britain's London 2012 Olympic gold medallists from 'Super Saturday' - Mo Farah, Jessica Ennis-Hill and Greg Rutherford - have won gold in Beijing

To which you can point out one detail, and then the critical one: the previous Olympic final had been won in 8.34m, and if it was all so easy, how come no-one else has been able to do it?

Rutherford, slowly and with several false steps, has learned what it takes. At the Worlds in 2007, he finished 21st in qualifying. Two years later, he jumped a British record of 8.30m in qualifying but could not back it up when it mattered and finished fifth, with a best jump of 8.17m, in the final.

Those lessons were absorbed. Injury destroyed his hopes at the Worlds in Daegu in 2011. Then, with the assistance of an unparalleled coach in Dan Pfaff, he redesigned his technique to ensure it never happened again.

It is not merely by happy chance that all three of Britain's gold medallists in the Olympic Stadium on 2012's Super Saturday have repeated the feat here in the Bird's Nest.

When the Olympics came to Beijing in 2008, all three were as low as sport can take you: Farah, eliminated in the heats; Ennis, watching at home in Sheffield with her fractured right foot in plaster; Rutherford, a footnote in the final in 10th, emotionally shattered after the death of his grandfather and rushed to hospital the following day with kidney and lung infections.

Greg Rutherford tweeted in March that he was having a long jump pit in his garden

All have come back to the sort of redemption that does not happen by accident and can only be achieved by very few.

In winning the big four, Rutherford has gone further still than those two friends and team-mates and become only the fifth British athlete after Daley Thompson, Sally Gunnell, Linford Christie and Jonathan Edwards to hold all the aces at the same time.

Rutherford has a habit, when taking his three dogs for long walks near his home outside Milton Keynes, of mentally rehearsing big finals, of commentating out loud on the scenes he pictures in his head.

He never sees himself finishing second. Neither, it now seems, do we.

- Published25 August 2015

- Published25 August 2015

- Published25 August 2015

- Published25 August 2015

- Published30 August 2015

- Published30 August 2015

- Published10 September 2015

- Published8 February 2019