Doping scandal: Can athletics learn from baseball & cycling?

- Published

On days like Monday, when sports administrators reach for their thesauruses to find new ways to tell you how appalling the latest scandal is, it is easy to get swept along by the outrage and forget that you have read these press releases before.

But we have, many times, and that is what is most depressing about these occasions: East Germany, Ben Johnson, Festina, Balco, Lance Armstrong…one day all this "disappointment", "disgust" and "shock" will really bite.

In truth, it is not even the first time we have heard Dick Pound, the chairman of the World Anti-Doping Agency (Wada) commission that has just delivered arguably sport's loudest rap sheet, in this form.

When it comes to delivering home truths, Pound has previous and he started his question-and-answer session in Geneva with a preamble that he described as taking a backswing.

Russia doping crisis in 60 seconds

The metaphor was apt, as Russian athletics is now in the same hole that American baseball - and therefore all baseball - found itself a decade ago.

That was when baseball and softball - an unfortunate bystander, damned by its obvious but innocent association with the men's game - were voted out of the Olympic programme by International Olympic Committee members fed up by Major League Baseball's refusal to release its stars for a few weeks every fourth summer and a reluctance to take doping seriously.

Working out which of these two big black marks was the most significant is not easy but it would be fair to say that the president of the Australian Olympic Committee John Coates was speaking for at least a few of his IOC colleagues when he said "problems with doping in US baseball probably cost the sport dearly".

Just to put this decision into context, these two sports were the first to be removed from the Olympics since polo in 1936.

Pound, then president of the Wada, had already called MLB's anti-doping rules "a farce", which was something of an understatement when you look at the "half a dozen strikes and you might be out" policy that passed for a deterrent in the years before that IOC vote.

That time is now characterised as baseball's "asterisk era" - nothing to do with indomitable Gauls but plenty to do with superhuman strength.

Baseball players, like many other athletes, had been dabbling with amphetamines for years, just to cope with the physical demands of a brutal schedule, but now they were also bulking up on human growth hormone and steroids.

The pitchers threw harder and the sluggers hit further. The crowds loved it. It was a scam, though.

The players had apparently missed MLB commissioner Fay Vincent's 1991 memo not to take steroids, please, and had instead taken them with impunity, almost literally. They were not even tested for steroids until 2003, and then only very rarely.

Russian doping 'worse than thought'

But lie, sorry, life could not go on like this, not when almost every other sport in the world was being forced to address the grim realities of doping.

The tipping point came when federal investigators were alerted to a shabby little sports nutrition business in California that appeared to be doing well on the back of some famous clientele.

At first, it looked like the Bay Area Laboratory Co-operative (Balco) might be guilty of run-of-the-mill tax evasion, but a trawl of the company's bins turned up a lot more than empty vitamin jars. That was in 2002.

The United States Anti-Doping Agency (Usada) joined the investigation and by 2005, many of track and field's biggest names would be implicated, with Balco's boss Victor Conte serving a four-month prison sentence, reduced in return for shopping his customers, including baseball's best player, Barry Bonds, for distributing steroids and laundering money.

San Francisco Giants star slugger Barry Bonds was a central figure in baseball's steroids scandal

Under pressure to punish offenders with more than a slap on the wrists, the MLB brought in a 10-game ban for a first positive test, 30 days for a second fail, 60 for a third, a year for a fourth and then penalty at the commissioner's discretion for a fifth.

That became 50 games for strike one, 100 for strike two and a lifetime ban for strike three - but the rest of Olympic sport demanded two-year sanctions for intentional doping and an agreement to random, no-notice testing.

It was almost as if baseball did not care about its Olympic place, which is probably true of MLB, but certainly not of fans and players in countries like Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Japan and South Korea.

However, the sport's reputation would get worse when, much like the current Russian athletics scandal, some investigative journalism forced the issue higher up the agenda.

The Game Of Shadows, written by two San Francisco Chronicle reporters, is the definitive account of Balco and Bonds is its brooding bad guy.

Baseball needed help. For so long America's most mythologised sport, it was being pummelled in the battle for media attention and national significance by the NFL, with basketball, motor racing and soccer coming hard on the rails.

Every big swing Bonds took on his way to breaking Hank Aaron's home run record in 2007 was booed, and he was then named in another of sport's great independent doping reports.

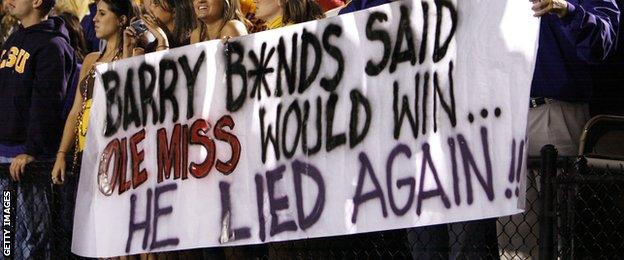

Rival baseball fans make their feelings known about Bonds

In his 409-page investigation, Senator George Mitchell was Pound-like in his punches: doping in baseball was "rife" and MLB's response had been "slow and ineffective". He named 89 players as cheats.

Bonds, convicted of perjury in 2011 only for that to be overturned on appeal, has not been forgiven by the wider American public and is still not in baseball's Hall of Fame.

More doping shame followed in 2013, with 14 players suspended for taking HGH, including New York Yankees superstar Alex Rodriguez, the Bonds of his day, who got an unprecedented 211-game ban.

Could it be that MLB was finally taking doping seriously?

It is now an 80-game ban for a first offence, 162 games (a season) for a second and a lifetime ban for a third.

Baseball and softball failed to get reinstated for the 2016 Olympics, and initially missed out on readmission in 2020, too.

But the political landscape has changed since that decision in 2013, with new IOC boss Thomas Bach keen to grow the Games again, and it now seems possible that the two sports will be on display at the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo.

Russia could be suspended - Coe

Is it truly rehabilitated, though? The evidence in the US is mixed.

MLB's 30 teams still attract enormous cumulative crowds for their 162-game marathons - the biggest total attendance in world sport - and TV ratings for these games in their local markets are solid.

But baseball is rarely part of the national conversation these days. This year's compelling World Series between the New York Mets and eventual winners the Kansas City Royals was the first for a while to command the attention of anybody but fans of those teams and diehards.

It is a narrative arc many cycling fans will recognise from the years immediately after Lance Armstrong's first retirement in 2005.

Armstrong was still a hero to many back then but some had already worked him out, including Pound, who never missed an opportunity as Wada boss to point out cycling's obvious shortcomings when it came to tackling its endemic drugs problem.

And he was given lots of chances: the Operation Puerto-ravaged start to the 2006 Tour, Floyd Landis' disgrace at the end of that race, Michael Rasmussen's ejection from the 2007 Tour whilst wearing the leader's yellow jersey and a steady stream of positive tests.

Cycling struggled from crisis to crisis during these years but it did soldier on and, in time, it started to get to grips with its problems.

Crucial to this was another one-two punch of fine investigative journalism, in this instance by The Sunday Times' David Walsh and others, and some more dogged anti-doping work by Usada to ensnare Armstrong in 2012.

When Armstrong finally admitted his cheating to Oprah Winfrey in early 2013, Pound suggested cycling could lose its cherished Olympic spot, particularly if it could be proven that the sport's governing body, the UCI, had covered up the American's doping.

Having been stripped of his seven Tour de France titles, former UCI president Pat McQuaid said: "Lance Armstrong has no place in cycling. He deserves to be forgotten."

It took some careful diplomacy from new UCI boss Brian Cookson to snuff that threat out before it got much traction, a sales job that was helped by his clear-out of the sport's old guard and the widely held view that cycling was getting cleaner.

But just to underline the opening point, Cookson also took the trouble to set up an independent investigation into the bad old years, a move that would clear his predecessors of the type of allegations the IAAF's former bosses face now, but portray them as ineffective in the fight against cheating as Vincent's memo.

Baseball and cycling have not recovered - anybody who has experienced the toxic scepticism of recent Tours will tell you that - but they are in recovery.

Both got to this stage by a combination of media scrutiny, improved leadership, better science and a general desire on the part of everybody involved in the sport to be less dirty.

One of the co-authors of the Russian athletics report, Richard McLaren, was also involved in Mitchell's baseball inquiry, and his memories of the mess MLB was in will give athletics chiefs some cheer today.

"That was pretty shocking, and it's taken them quite a number of years since to straighten the matter out," McLaren told the BBC's World Service.

"They're in much better shape than they were and I think athletics will no doubt recover from all of this as well. But it's going to take some hard work to change what's going on."

So there is a roadmap to redemption should Russian sport want to take it.

Related topics

- Published9 November 2015

- Published9 November 2015

- Attribution

- Published9 November 2015

- Attribution

- Published9 November 2015