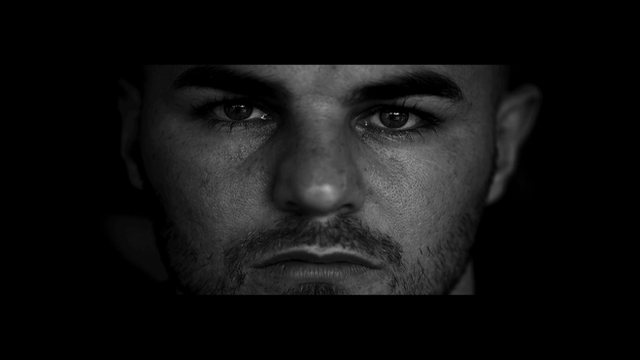

Kevin Mitchell: The reformed party boy with eyes on a world title

- Published

Kevin Mitchell has won 39 and lost two of his professional fights

Jorge Linares v Kevin Mitchell |

|---|

Venue: O2 Arena, London Date: Saturday, 30 May |

Coverage: Live text commentary on BBC Sport website from 19:45 BST |

In the build-up to his world title fight against Venezuela's WBC lightweight champion Jorge Linares on Saturday, Kevin Mitchell talks to BBC Sport about the dark side of boxing and battling demons, in and out of the ring.

John L. Sullivan, boxing's first gloved heavyweight world champion, provided the template in the 19th Century. Boxers have had a lot of time to learn. Many never do.

When Sullivan wasn't battering foes in the ring,, external he was battering foes in the bars of Boston, emptying keg after keg of whiskey, spending like a medieval king and increasing the families of a multitude of women.

The devil finds plenty of daft things for idle hands to do and elite boxers have more spare time on their hands than most.

It partially explains why Battling Siki,, external light-heavyweight world champion in the 1920s, walked his pet lion down the Champs-Elysees while wearing a top hat and tuxedo, with pistols on his hips. Before being shot dead, alcoholic and penniless. And why Sugar Ray Robinson,, external the greatest boxer who ever lived, drove a pink Cadillac and had a jester in his entourage. Before dying from Alzheimer's, lonely and penniless.

The list is endless, and it doesn't matter where a boxer comes from. Terry Spinks, a salt-of-the-earth Cockney who won gold as an 18-year-old at the 1956 Olympics, was also seduced by celebrity. "When you're a famous personality," said Spinks, "you've got to look like one."

Terry Spinks was the toast of London's East End after winning gold at the 1956 Olympics

Looking like a famous personality meant more of that carousing, which fast corroded him as a fighter. Kevin Mitchell, who challenges Venezuela's Jorge Linares for the WBC lightweight title in London on Saturday, knows where Spinks, a fellow alumni of West Ham Amateur Boxing Club, is coming from, what he went through and how he ended up.

Spinks never fulfilled his potential. Mitchell just might.

"You know what? I never thought it would be such hard work," says the 30-year-old, who won the ABA featherweight title at the age of 18 and was consequently tipped for great things but has so far come up short.

"Boxing is a weird career. From the age of 10 to the age of 18 I lived like a monk. Then, all of a sudden, the madness kicked in.

"One day I was asking my mum for £2, so I could buy a chip roll and a can of Dr Pepper from the takeaway. The following day I signed a pro contract and had a load of money in the bank.

"After I had my first pro fight I started being recognised in pubs and clubs. Before I knew it I was a bit of a party boy and walking down the wrong road. But boxers are supposed to be athletes; it just doesn't work."

Mitchell was easily beaten by Australia's Michael Katsidis at West Ham's Upton Park in 2010

Actually, it worked for a while. Mitchell won the British super-featherweight title in 2008, after a ding-dong battle with Carl Johanneson from Leeds. In 2009, he easily out-pointed dangerous Colombian Breidis Prescott, who had knocked out Amir Khan in one round the previous year., external After which, the partying caught up with him and brought him crashing down.

In 2010 at Upton Park, home of his beloved West Ham United, Mitchell fought seasoned Australian Michael Katsidis for a fringe world title and was taken apart inside three rounds. , external

Mitchell's preparations for the fight consisted of emotionally debilitating rows with his then girlfriend, a hell of a lot of wasted time in the boozer and not enough quality time in the gym - the ingredients for failure.

"It's important for any athlete in any sport to have a clear mind, so that you can work on certain things, study your opponent, come up with game plans," says Mitchell.

"But a lot of the time I didn't want to be there. Sometimes I just wouldn't turn up. I had to go on a crash diet to make the weight. I should never have been put in the ring, people should have been looking out for me.

"Then getting beaten in front of 24,000 people at Upton Park, all my friends and family, it destroyed my pride and broke my heart.

Mitchell's life in boxing |

|---|

Born: Romford, Essex, 29 October 1984 |

Amateur honours: ABA featherweight champion, 2003 |

Turned pro: 17 July 2003 |

Pro record: 41 fights, 39 wins (29 KOs), two defeats |

Pro honours: Former British & Commonwealth super-featherweight titles |

Best wins: C Johanneson (TKO9, 2008); B Prescott (PTS, 2009); J Murray (TKO8, 2011); D Estrada (TKO8, 2015) |

"After the Katsidis fight I came close to jacking it in. I hated the sport. I hated the politics. I was fighting in arenas and football grounds and thought I should have been paid better.

"I did nine straight months on the booze, did all my money - about £180,000 - and got myself depressed. The drink doesn't work for me. In fact, it's never a good thing for anyone."

Alarmed by their son's self-destructive behaviour, Mitchell's parents staged an intervention, literally dragging him out of a pub and telling him how he might end up - alcoholic, lonely and penniless.

Some of their words must have hit the mark, because a few months after being arrested on suspicion of possessing cocaine and running a cannabis farm,, external Mitchell stopped rough, tough Mancunian John Murray to get his career back on track. But he was soon derailed again.

"John was ranked number one by the WBA and I knocked him out, on a promise I'd get a world-title fight," says Mitchell.

"But they offered me chump change to fight Brandon Rios in New York and John got the title shot instead. I was very, very angry about it, out of the ring for another seven months and back on the booze."

Mitchell gave the best performance of his career so far in stopping Mexico's Daniel Estrada in January

Two fights later, Mitchell fought Scotland's then WBO lightweight champion Ricky Burns and was stopped in four rounds. Many boxing fans and writers thought he was finished. Some, tired of the excuses, could not have cared less whether he had more left in the tank or not.

But one man who saw a fighter brimming with potential where others saw a hollowed-out husk was promoter Eddie Hearn, who took Mitchell off the hands of his rival Frank Warren and showered him with love.

"Now I'm with the best team in the world," says Mitchell. "Eddie is passionate about his fighters, is up and down the country making sure they're OK, and loves the sport.

"Barry [Eddie's father and the head of Matchroom Sport] is from my area, Dagenham, and is a proper person, a good person. They know what's going on and know me inside out."

Ray Winstone profiles Kevin Mitchell

In 2013, Mitchell was persuaded by his now fiancée, Jodie, to contact his old amateur trainer Tony Sims and the last piece of the puzzle fell snugly into place.

"Tony is a great trainer and also a tremendous mentor," says Mitchell, whose previous trainer was Jimmy Tibbs, who also handled British world champions Frank Bruno, Barry McGuigan and Nigel Benn.

"He keeps me in line, just like he did when I was a kid. He rings me up all the time, asks me what I'm up to, how the kids are (Mitchell has two, Connor and Vincent, 10 and five). I couldn't have come back without him."

The boxing world is littered with patron saints of lost causes but in taming Mitchell and guiding him to a second world-title shot, Sims has worked a bigger miracle than most.

Mitchell dazzled in beating Mexico's Daniel Estrada last time out and will need to be similarly inspired to dethrone Linares, a three-weight world champion with five knockouts from his last six fights.

But if Mitchell does beat Linares at the O2 Arena, having followed so many boxers down the wrong road and managed to find his way back again, don't expect the celebrations to last too long.

"I've had some mental, mad parties, the craziest you can think of," says Mitchell. "But I don't miss it. I'm done with all that messing about.

"My ambition is to win a unification fight and get out with my finances straight and my faculties intact. That sounds good to me." Amen.

- Published15 April 2015

- Published29 May 2015

- Published31 January 2015

- Published22 September 2012

- Published17 July 2011

- Published11 June 2018