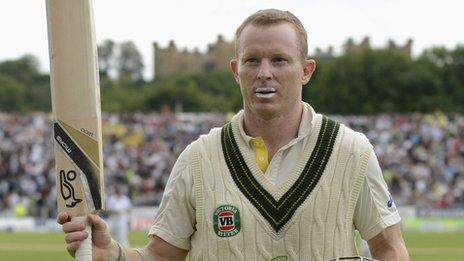

Ashes 2013: Chris Rogers the unlikely superhero in fourth Test

- Published

Chris Rogers

Chris Rogers does not look much like the classical sporting hero. Almost 36 years old, a short-sighted spectacle wearer who is also colour-blind, he is less Superman than Clark Kent, Peter Parker rather than Spider-Man.

His alter-ego would scare few: Meticulous-Man, or perhaps the Ginger Limpet. Neither would his superpowers intimidate many: the ability to concentrate for long periods, a proficiency in working singles off his legs.

Before Saturday, he also had the curious honour of having scored more runs against his country than for it, courtesy of a double-century and 56 for Leicestershire against the touring side of 2005., external

The comic-book covers might have to wait. Yet Rogers came to Australia's rescue here in Durham as effectively as any caped crusader, his unbeaten 101 taking his side from collapse at 49-3 to control at 222-5 by stumps, a mere 17 shy of overhauling England's under-par total.

Never was it easy. On a morning when Stuart Broad looked likely to unload one of his cluster-bomb spells - an explosion of wickets after a period of strange silence - Rogers could only watch as his partners came and went with barely enough time to wish him well.

After lunch, as Broad ripped ball after ball past his poking blade, found his outside edge only to have the chance spilled in the slips, and nicked the inside to watch in disbelief as the stumps somehow survived, he looked a wicket in waiting, his technique wobbling, his zinc-creamed lips pursed.

Given out caught behind by umpire Tony Hill, he had come back from the dead not once but twice - first when a review suggested no discernible edge, and then again when Hawk-Eye showed that he was probably lbw but that Hill, having not given his decision on that mode of dismissal, had no umpire's call to be judged upon.

If that was chaotic, the next five and a half hours were tranquil, all the way until Rogers found himself on 96, a single shot away from becoming the second oldest Australian in history to score a maiden Test ton.

Ashes 2013: Chris Rogers delighted with maiden Test century

Rogers is accustomed to being patient. He was part of the same Australia Under-19 team in 1996 as Brad Haddin, Nathan Bracken and David Hussey, only for his Test debut to be delayed for another 12 and a half years. When it finally arrived, he faltered and had to wait five and a half more years for his second.

It only made the final deferment all the harder to bear. For half an hour he was neutered, ball after ball from Graeme Swann giving him nothing to hit and plenty of reasons to have kittens.

Twice he played and missed outside off stump, the image of Swann putting his hands to his head mirrored the length of a packed Australia dressing-room balcony. With 20,000 first-class runs to his name, he could not find the finishing four.

At last, desperately, with darkness closing in, he swung a sweep at a slightly wider one, ran hard and stopped, almost in shock, as the ball skipped over the rope at deep square leg.

Rogers had every right to think this moment would never happen, kept well away from the Australia opening slots year after year, first by greats like Michael Slater, Justin Langer and Matthew Hayden and then wannabes like Phil Hughes and Shaun Marsh. When obdurate old boys were required, Simon Katich got the nod; when experience was required, Shane Watson was always recalled.

Even on his eventual chance, after a journeyman's odyssey encompassing spells with four English counties and two Australian state sides,, external he appeared fated to fail.

His dismissal at Lord's, incorrectly given out lbw to a slow full toss that he somehow missed, might even go down as the worst dismissal in Test history. When he got within 16 runs of a century at Old Trafford, he was distracted by an old mate behind the bowler's arm and trapped lbw.

Moments long dreamt about can often feel surreal when they finally take place. So it was with Rogers. While the entire ground rose to him, the hero of the hour took time to react. There were no fist-pumps, no bear-hugs for his partner and old team-mate Haddin, just a suitably old-fashioned point of bat to four corners. Only his shaking hands gave a clue to the emotions inside.

"It is the sweetest moment of my cricket career," he admitted, somewhat unnecessarily, in the aftermath.

"It may have been one of those days for me - things just seemed to go my way. You just had to chip away, and fortunately I had some luck. It was good to make it count. After all this time to play and get a Test hundred is very satisfying."

Only five players have made more first-class centuries than Rogers before recording their maiden Test hundred. One of them was his coach here, Darren Lehmann, another Australian who plundered county attacks but was a nearly-man at national level for much of his career.

At an age when most Test batsmen are thinking of retiring, Rogers appreciates that his opportunities to make hay are limited. He is a stop-gap, a fall-back.

Even outside the context of this match, it makes this innings all the more poignant. Rogers to the rescue indeed. All hail the Eternal Flame.

- Published10 August 2013

- Published10 August 2013

- Published10 August 2013

- Published9 August 2013

- Published7 August 2013

- Published18 October 2019