Where are England going wrong in one-day international cricket?

- Published

England have lost 108 of their past 229 ODIs

It's the question everyone is asking. How can England be ultimately so dominant in a five-Test series, and then, against the same opposition in one-day cricket, be so inept?

It is the same game, after all. Well, isn't it?

Actually that is part of England's problem. Always has been ever since one-day cricket was invented. It ISN'T the same game.

Yes, it does feature a bat, a ball and some stumps. But in most other ways, one-day cricket is entirely different. In fact, with its fast evolving skills and strategies, it is less the "same" than it has ever been. And yet England play it in roughly the "same" way. There's your basic answer.

BBC cricket correspondent Jonathan Agnew |

|---|

"It will always be difficult for England to win a one-day World Cup, but they would certainly stand more chance if they gave greater thought to the type of tactics and personnel who would make them successful. The most important thing is that you assert yourself over the bowlers. You have to make them terrified of bowling to you, just as India openers Ajinkya Rahane and Shikhar Dhawan did on Tuesday." |

Essentially, England's focus has always been on Test cricket. That is where most of the resource is directed. One-day series are a necessary add-on to satisfy TV paymasters and bring in cash.

Usually the England one-day team is a sort of trial zone for future Test players, to see if they can handle the extra demands of being an international sportsman.

It is picked by the same selection panel, usually has the same captain and a nucleus of the Test team. It was always believed that a good cricketer could adapt to whatever format of the game he found himself in.

That has changed. The one-day game is almost unrecognisable from the Test match version, as the coloured pyjamas worn starkly illustrate.

ODIs played in last 10 years | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Team | Played | Won | Lost | Run rate |

Australia | 263 | 168 | 78 | 5.65 |

India | 289 | 164 | 107 | 5.44 |

S Africa | 197 | 126 | 63 | 5.38 |

Sri Lanka | 275 | 144 | 115 | 5.36 |

England | 229 | 107 | 108 | 5.14 |

*statistics correct as of 3 September 2014 | ||||

The limitations on bowlers, both in terms of number of overs allowed and where they are allowed to bowl, are crippling. The fielding restrictions (a maximum of four men permitted outside the circle) and the proximity of the boundary rope are cruel (yes, here a bowler, external speaks). Some of the shots batsmen attempt are crazy.

An average 50-over score is now 275. Yes, AVERAGE. (It was 230 a few years ago). There have been 49 scores of over 300 in the last two years (almost a third of the innings played).

Yet England continue to play it like a Test match. Deliveries are left in the first five overs (despite there being only two boundary fielders allowed) and orthodox shots played. Balls outside off stump are hit to the off side, where most of the fielders are.

No English player would ever have done what the great Indian opener Virender Sehwag did. He hit the first ball of a World Cup match, external - bowled by South Africa's Dale Steyn - back over the bowler's head for four. Everyone gasped, even the bowler. Sehwag just leaned contentedly on his bat. That type of thing came naturally to him.

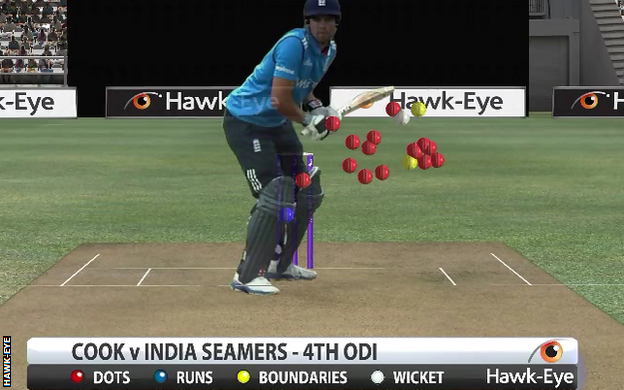

Alastair Cook is doing his best, by heck he is, but he hasn't got the game for this format. Look at his "beehive" from his innings at Edgbaston on Tuesday (above). All the red balls outside off stump were dot balls. many of them were quite wide - effectively a free hit. Most good one-day batsmen are brutal on anything wide. But such are Cook's struggles that he can't regularly score off those balls.

Further evidence is presented by his score chart during the India one-day series. A very high proportion (54%) of his runs are scored behind the wicket, illustrating that he is mainly a deflector of the ball. There are few shots straight and only 1% of his runs are scored through mid-off. This means he is much easier to set a field to.

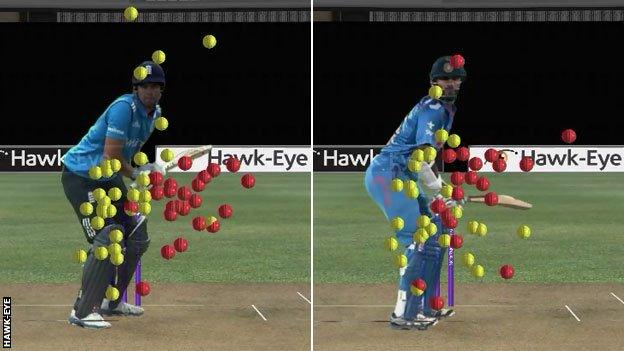

Compare that with a similarly "orthodox" opening batsman like India's Ajinkya Rahane. He is by no means a "slogger", but much more aggressive and proactive. On his score chart, only 23% of his runs come behind the wicket, and 77% in front. Nearly 40% of his scoring shots are down the ground.

You don't want to be too predictable either. Cook will invariably hit off-side balls to the off side and leg-side balls to leg, in Test match style. He is easier to set a field to. India's left-handed opener Shikhar Dhawan is much more versatile, often hitting the ball on the opposite side to where it's pitched - and therefore where the fielders aren't.

Cook and Dhawan's scoring shots against seamers: yellow balls indicate runs scored on the leg side, red balls indicate runs scored on the off side

This is not supposed to be a personal attack on Alastair Cook. These traits apply across the board. Aggression, calculated risk and innovation are necessary at any stage of a one-day innings, and England are rarely able to provide it.

Only two of their batsmen, Jos Buttler and Eoin Morgan, have strike rates above 80 and are therefore in the list of the 100 fastest scoring batsmen in one-day cricket. (Alex Hales is not included in this list as he has not played enough ODIs).

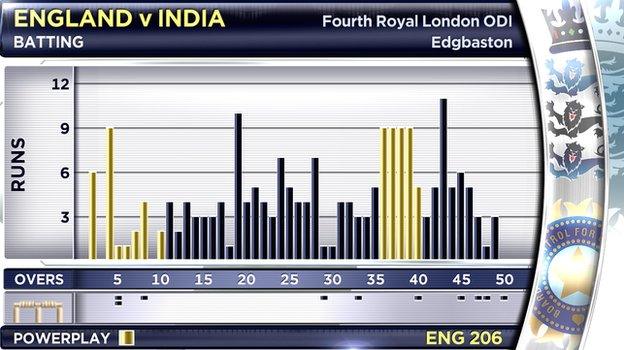

This reflects in England's approach when wickets fall. They studiously rebuild (as you might in a Test match), even in the powerplay overs - as seen below in the "Manhattan" graph of their innings at Edgbaston.

England played conservatively after losing wickets at Edgbaston

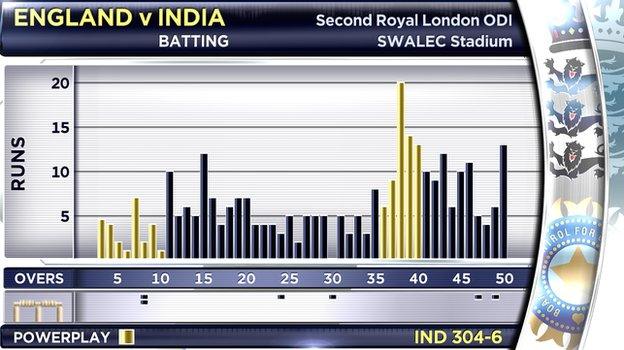

They got stuck, and, despite Moeen Ali's sublime efforts, failed to post a decent score. Yet India, in a similar tricky early predicament at Cardiff when they were 19-2, continued to bat with purpose and intent, going at five and eventually six an over throughout, eventually posting 304 (see their Manhattan graph from that innings below).

There is an inherent trust in each other among the Indian batsmen, right down the order, and a mutual understanding to maintain momentum whatever the situation. It is an enlightened approach embedded in their team culture.

England's batting mentality is, barring a couple of notable exceptions, rooted in conservatism. It was ever thus. That is why England have never won the World Cup and are not likely to any time soon.

Listen to the Test Match Special podcast where Jonathan Agnew, Graeme Swann, Alec Stewart and Michael Vaughan discuss the future of England's one-day international side.

India were more positive at Cardiff, despite two early wickets

- Published3 September 2014

- Published2 September 2014

- Published3 September 2014

- Published2 September 2014

- Published25 August 2014

- Published29 August 2014

- Published13 July 2014

- Published18 October 2019