Lance Armstrong case creates an unlikely hero

- Published

- comments

You have probably never heard of Scott Mercier, a little-known former professional cyclist.

Yet his name came up time and time again during the United States Anti-Doping Agency's (Usada) investigation into Lance Armstrong and the US Postal team.

So Travis Tygart, Usada's crusading chief executive, knew he needed to track Mercier down and talk to him.

"I got this call, out of the blue, and thought it must be a joke," remembers Mercier, now a financial adviser living in Grand Junction, Colorado.

"Travis said 'I want to thank you. And I want to find out why you were able to do what no-one else could'."

Mercier admits he's often wondered "where would I have ended up" if he had have doped

Because Mercier, 44, was the US Postal rider who resisted the pressure to dope.

To do so, he had to turn down the offer of a new contract with the team and quit the sport he loved.

He can still clearly remember the day he made up his mind, in May 1997, at the age of 28, after a conversation with the team's doctor, Pedro Celaya.

"Pedro called each member of the team into his hotel room, one by one. When my turn came, he handed me a bag containing a bottle of green pills and several vials of clear liquid.

"I was also given a 17-day training schedule and each day had either a dot or a star. A dot represented a pill and a star was an injection.

"He said 'they're steroids, you go strong like bull'. Then he said 'put it in your pocket, if you get stopped at customs say it's B vitamins'.

"That was when I decided I didn't want to be a pro cyclist any more. I got home and decided 'no thank you'.

"I love cycling, it's a beautiful sport, but it would have been very challenging for me to look someone in the eye and say I was clean when I knew I wasn't.

"People talk about the health aspects, but to be totally honest I wasn't so concerned about that.

"For me, it was the lying and the hypocrisy."

Several other former US Postal riders detailed Celaya's involvement in doping during the Usada investigation and he was charged with "possession, trafficking and the administration of doping materials and methods".

Celaya, now the team doctor with Radioshack, external, has contested the charges and his case is due to go before the Court of Arbitration for Sport later this year. He also strongly disputed Mercier's claims when contacted by BBC Sport.

Mercier said this was the first time he was given drugs, although it had been obvious that his team, and indeed many of the others, were doping.

There was the refrigerator in the team truck which they nicknamed "the special lunchbox", because it was filled with EPO., external "You could hear the glass vials shaking together when you moved it," he recalls.

His wife remembers him talking about the steroids they found in team-mate George Hincapie's shoebox. And Celaya had talked about him needing to take "extra B vitamins" to boost his haematocrit levels, which he clearly took as meaning he should take EPO.

Mercier had tried doing the training programme without using drugs, but found it impossible. "I could do the first two days, but by about the fifth hour on the third day I couldn't do the efforts, I was getting fatigue and had to take a recovery day."

He also found he couldn't keep up with riders he had beaten easily a few months earlier on tours in North America and Asia. There was no test for EPO at the time, so it was essentially open season for riders who wanted to take it.

How does blood doping work?

"You get frustrated when your peers are beating your head into the gutter," he says, the frustration still in his voice. "When you're at an Amstel Gold Race, external and you can barely hold the wheel of the guy in 80th place.

"That same guy, you smoked three months previously. And you're thinking 'I've been training. I've lost two, three kilos. How is this guy suddenly so much better than me?'"

He remembers asking Hincapie, his team-mate, friend and flat-mate, about doping over a coffee in Girona, Spain, one day in March 1997.

"He didn't give me a yes or a no, he just said 'you'll have to make your own decision'. I took that to mean that yes, there is a fair amount and if you want to be a pro you'll have to do it."

On Wednesday, Hincapie expressed his regret at having doped throughout his career.

After leaving the sport, Mercier moved to Hawaii to run a restaurant with his father. He then settled in Colorado and became a financial adviser. He is married and has a son and daughter, but admits he has spent some of the last 14 years wondering what might have been.

"I would see the likes of Tyler Hamilton and George Hincapie having great success in the Tour and wonder 'where would I have ended up?'

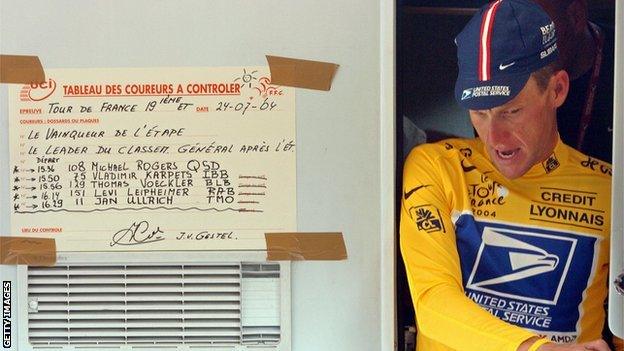

Armstrong and Hamilton racing against each other in 2004

"It was difficult for me because I knew what they were doing. They were walking around with this air of superiority, which really grated me.

"Clearly I would have made more money. Those guys were making seven figures and I haven't made anywhere close to that, but life works."

Mercier's world was far removed from that of professional cycling until a few months ago, when Usada began to investigate Armstrong and US Postal.

"It certainly gives me some validation for the decision I made," he says. "It wasn't that I wasn't good enough, it was just that I made different choices. They talk about winning at all costs, but are you willing to push well beyond the limits?

"I'm not, I think there's more to life than that. Sport should be a level playing field and it wasn't. It was who had the best team and resources and the best medicine and that wasn't the game I wanted to play."

After Usada's full findings came out on Wednesday, Mercier's wife called him. "She said 'imagine you're sitting down with your son and daughter, explaining hey, daddy's a liar and a cheat'. I don't have to do that."

Lance Armstrong: Usada reveals doping evidence

And what does he think of Armstrong, who joined US Postal the season after he left?

The duo were on the same team at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics and had sporadic contact in the years after that.

"He was a brash young man back then, but clearly had drive and talent," Mercier says.

"To come back from the illness he had was truly astounding, no-one can take that away from him.

"But the methods he used to achieve his success were fraudulent. His story is the greatest in sport but it's also the biggest fraud."

Celaya was sacked by US Postal in 1999 and replaced by Dr Luis Garcia Del Moral. The reason, according to another US Postal rider, Jonathan Vaughters in his evidence to Usada, was that "Armstrong did not feel that Celaya was aggressive enough in running the 'program'."

Mercier now thinks there should be an anonymous telephone number that whistleblowers can call to report their suspicions of doping, and that sanctions should be strengthened so that teams as well as individual riders can be banned.

He also believes the current leadership of the UCI must be replaced because they are "part of the problem, not the solution".

Above all, he hopes no rider ever again has to leave the sport they love because they want to ride clean.

- Published12 October 2012

- Published13 October 2012

- Published12 October 2012

- Published12 October 2012

- Published11 October 2012

- Published10 October 2012

- Published24 August 2012

- Published24 August 2012