Chris Froome: Tour de France win was worth the wait

- Published

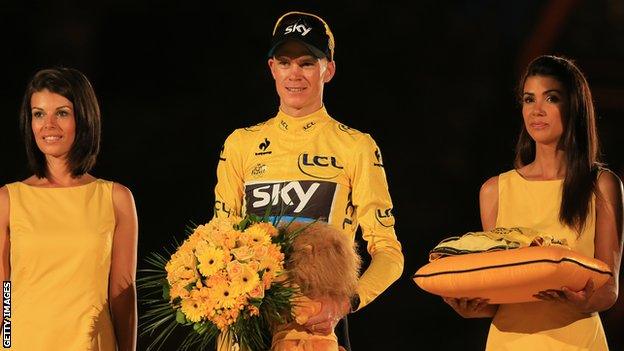

Chris Froome on the podium in Paris

Has a dominant sporting performance, on the biggest possible stage, ever started in such embarrassing fashion as Chris Froome's Tour de France victory?

The pre-race favourite had barely been riding for a minute of the 100th Tour when he clipped a Corsican kerb and fell off his bike.

Strictly speaking, the race had not even started - the 198 riders were still in formation lap-mode - but there he was, the man to beat, on the tarmac, with a skinned knee, watching the rest of the field disappear down the road.

Somebody should have taken a picture because we would not see that scenario again.

When the leading man takes centre stage at the start of the second act, and then spends the rest of the play delivering all the best lines, it is hard to remember a single, defining piece of drama.

Did Froome win the yellow jersey on the climb to Ax 3 Domaines? Or was Britain's second straight victory in cycling's most famous race secured the following day, when he defended his lead against the massed ranks of his rivals?

What about the controlled aggression of that ride to Mont Saint-Michel, the epic triumph on Mont Ventoux, his scintillating descent to Chorges, or his consistent excellence in the Alps?

The truth of it is that Froome has utterly dominated this Tour. There was no single race-deciding moment. There was a succession of emphatic confirmations that the Kenya-born Brit is the best all-round cyclist in the world.

That statement might provoke some protests from fans of Vicenzo Nibali, who missed the Tour to target his home race, the Giro d'Italia, but pretty much every other Grand Tour hopeful was on the start line in Porto-Vecchio, and the Team Sky star has thrashed them all.

Froome was also three minutes better than Nibali in last year's race, when he so memorably reined in his attacking instincts to help Sir Bradley Wiggins to glory, a knighthood and national treasure status. Wiggins, of course, was the other absent contender this year.

Listen to Froome's Tour de France win

In fact, so good was Froome in 2012 - he was seven minutes better than anybody also riding in this year's race - that perhaps the only real surprise about 2013 is that anybody is surprised at all.

Last year, the 28-year-old was the second-best rider over a course tailor-made for Wiggins. Why should he not be the best rider over a new course better suited to his more multi-dimensional skills?

Sport, of course, does not always comply with such logical certainties, and there is a world of difference between looking like the next great champion and becoming one.

Twice a runner-up at one of cycling's "big three" races, until Froome had actually won one there would always be scepticism about his deal-closing credentials.

These understandable doubts were less understandably fuelled by his unsuccessful attempt to win the Vuelta last year. Tacked on at the end of an exacting season in Wiggins' service, a tired Froome was given command of the Team Sky fleet in Spain.

He would finish a distant fourth, beaten by a rested Spanish armada of Alberto Contador, Alejandro Valverde and Joaquin Rodriguez.

Some took this as evidence of an inability to step up to the leadership role, or a weakness under fire.

Then there were those that insisted that with Contador back after his drugs ban, and fuelled by his own sense of the injustice of it all, the two-time winner would be too wily for the relatively unraced Froome.

Chris Froome (left) had to play a supporting role to Team Sky team-mate Sir Bradley Wiggins at last year's Tour

Throw in the returning 2010 champion Andy Schleck, a confident Rodriguez and a well-supported Valverde, and it was not impossible to build an argument for Froome being the underdog here in France.

But it is now clear that the gainsayers were looking too hard for reasons to doubt what their eyes should have told them in France - Froome is the future.

If truth be told, this race was over after the first weekend in the mountains. Froome's ferocious acceleration away from Contador and co halfway up the final climb on stage eight looked like it had been a long time in the planning.

A year of frustration at being told to slow down when riding for Wiggins was suddenly unleashed in what would become a trademark Froome burst - head down, elbows out, shoulders wiggling. The fact that only his team-mate Richie Porte could get anywhere near him simply reinforced the idea that we had just seen the next Tour champion.

Then we had perhaps the Tour's most remarkable day's racing in decades, a day that strangely humanised Team Sky's reputation for robotic brilliance and rescued the race as a piece of competitive drama for at least another week.

A series of withering attacks from the teams of Froome's main rivals left him alone with more than 100km to ride and three mountains to navigate.

For a man who came to professional road racing relatively late, and had sometimes struggled tactically in the past, this was a crisis. But for the next four hours, Froome demonstrated just how much he has grown as a rider in the last two seasons, and when he rolled into Bagneres-de-Bigorre with his main challengers the danger was not just averted, it was winked at.

But for as long as there were doubts about his team-mates, the race for yellow was theoretically alive. These doubts grew again on the 13th stage when Contador's team of wily veterans caught Team Sky napping in a crosswind and stole back some time: a rare triumph for Froome's foes.

Then it was over again. Mont Ventoux on Bastille Day did not really need any cycling fireworks to add to the sense of occasion, but Froome provided them anyway. Two vicious accelerations away from Contador and Colombia's Nairo Quintana left British cycling's new hero alone on the road where Britain's first Tour contender, Tom Simpson, so tragically died back in 1967.

It was perhaps inevitable then, that Froome would spend the next 48 hours defending himself against insinuations of doping. At times during the last month it has seemed that his most uncomfortable moments have come during the rest days' media conferences.

With this being the first post-Oprah Tour, there was always going to be a degree of collateral damage for this year's winner. But it is to Froome's credit that he has not let the media's guilt for giving Lance Armstrong an easy ride for so long derail his progress towards Paris.

Perhaps it's simply a sign of the confidence that comes from having a clear conscience. As he said in his victory speech: "This is one yellow jersey that will stand the test of time."

After Ventoux, Froome's progress was almost regal. A third stage win came when he calmly changed bikes at the top of the last climb in stage 17's time trial, before plummeting down towards Chorges to beat Contador again.

The Alps, where Contador had promised to stage a third-week comeback, were almost an anti-climax. Even on a rare off-day, when Froome made every amateur rider's worst mistake by not eating enough on Alpe d'Huez, he managed to stretch his lead at the top.

Stages 19 and 20 passed without any major incident, except to confirm that Contador is yesterday's man and tomorrow belongs to Froome, his close friend and wingman Richie Porte, Quintana and whoever else can emerge from the exciting group of young riders who provide so much hope that cycling can move on from the Armstrong era.

But none more so than Froome. He might not be as "British" as some would like their sporting heroes to be, or as ready with a quip as Wiggins, but he is very good and he is getting better.

It is entirely possible that in four years' time we will be talking about him as one of the all-time greats.

Not bad for a bloke who fell off his bike a mile into his biggest race.

- Published22 July 2013

- Published21 July 2013

- Published20 July 2013

- Published20 July 2013

- Published20 July 2013

- Attribution

- Published20 July 2013