Margaret Thatcher 'never really understood sport'

- Published

Margaret Thatcher was many things - a workaholic, a zealot, a Prime Minister who, even in death, continues to divide and polarise opinion like few before and none since.

One thing she was not was an instinctive lover of sport. "She tried occasionally to show an interest," says her successor John Major, "and dutifully turned up to watch great sporting events, but always looked rather out of place."

Despite, or because of, that natural antipathy, Thatcher nonetheless had a significant impact on British sport during her 11 years in power.

"She never really understood sport until it migrated - and sometimes mutated - beyond the back page, or impacted on other areas of policy," Lord Coe has said. But migrate and mutate it did.

Here, BBC Sport looks at five areas of the sporting landscape on which Thatcher left her indelible mark.

1980 Olympics

When US president Jimmy Carter proposed that the Moscow Games be boycotted in protest against the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan, Thatcher was as quick with her support as the International Olympic Committee was with its opposition.

First to the British Olympic Association, and then its star athletes, she and her government began a concerted campaign to end any British involvement.

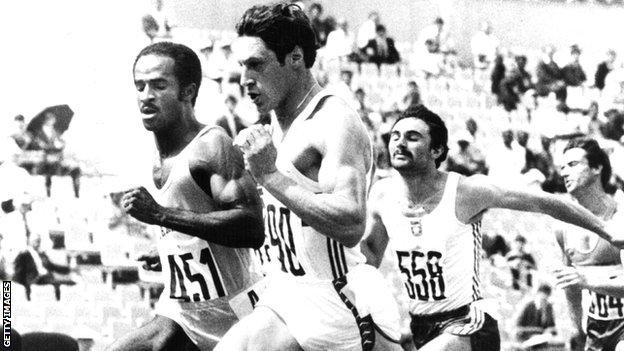

Scotland's Allan Wells (centre) won 100m gold at the Moscow Olympics, a Games which Margaret Thatcher asked the BOA to boycott

"The Games will serve the propaganda needs of the Soviet Government," she wrote to Sir Denis Follows, then BOA chairman. "I remain firmly convinced that it is neither in our national interest nor in the wider Western interest for Britain to take part in the Games in Moscow.

"As a sporting event, the Games cannot now satisfy the aspirations of our sportsmen and women. British attendance in Moscow can only serve to frustrate the interests of Britain."

When the BOA refused to acquiesce, the athletes were targeted. Sprinter Allan Wells was sent four packages from Thatcher's office, their intention clear.

"One of the pictures I received from 10 Downing Street was of what looked like a dead young girl, face down, with an outstretched arm reaching for a doll," Wells told BBC Sport last summer.

"The letter had words to the effect that this is what the Soviet army are doing in Afghanistan. But I was going, and that decision was taken when I saw the letter with the picture in it.

"You've got to sit up when you get letters from the government and I gave it a lot of respect, but if I didn't go it wasn't going to make any difference to what was happening in Afghanistan."

Wells - just like his fellow British gold medal winners that summer, Daley Thompson, Duncan Goodhew, Steve Ovett and Seb Coe - would stand on the podium with the Olympic anthem playing rather than God Save the Queen, facing the Olympic flag rather than Union Jack.

Nick Robinson looks back at the life of Margaret Thatcher

To this day, Coe is convinced he and his team-mates did the right thing - not least for the impact it would have many years later on London's hopes of staging the 2012 Games.

"Using (sport) as a weapon was both craven and self-defeating," he has said.

"In hindsight it was a good decision to go for all sorts of reasons. I don't think I would have been able to stand up in Singapore (in 2005) in front of the IOC and say what I said with credibility if I had boycotted in 1980.

"I was able to say that Britain had sent a team to every winter and summer games. Had I not gone in 1980 it would certainly have been seized upon and exploited by rival cities."

Thatcher, ever keen to reduce public spending, would never fall for the notion of a home Olympics as later Conservative politicians did.

When Birmingham bid for the 1992 Games, it did so without full government financial backing. The government only guaranteed losses in excess of £100m, with Birmingham City Council liable for the first portion.

The city's official letter of support was signed not by the Prime Minister but merely by Kenneth Baker, the Secretary of State for the Environment.

ID cards

The footballing landscape of the Thatcherite era was unrecognisable from today's cosmopolitan, billion-pound Premier League product.

Played in frequently dilapidated stadia, haunted by the threat of hooliganism, watched by spectators penned in behind high wire fences, it was a world Thatcher had never experienced through a fan's eyes and seldom appeared to understand.

Football supporters endured dilapidated stadia and high wire fences during much of the 1980s - such as in this Birmingham v Leeds match in 1985

Lord Moynihan, Minister for Sport under Thatcher from 1987 to 1990 and chairman of the BOA during the 2012 London Olympics, on Tuesday defended the former Prime Minister's record.

"I was extremely fortunate to be able to work so closely on the major issues of the day with the greatest leader I have known - the terrible human tragedy of Hillsborough, the first European Agreements on tackling doping in sport, the establishment of the British Paralympic Association, the building of a close relationship with the International Olympic Committee, the modernisation of British sport - all during an era when we had to face, tackle and seek to eradicate the scourge of football hooliganism at home and abroad."

Not all football fans share his enthusiasm for the methods chosen.

Heavily influenced by outspoken Luton Town chairman and Tory MP David Evans, who saw the plan as a way to stamp out hooliganism, Thatcher brought in legislation under the Football Spectator Act of 1989 for a 'National Membership Scheme'.

Access to football grounds would be restricted to those in possession of an ID card. The casual fan would be denied; the away fans, as they were at Kenilworth Road, might be banned altogether.

Critics complained that the possibility the vast majority of supporters might be law-abiding citizens seemed not to be considered.

Neither did the technological issues with the cards, or concerns about queues building at turnstiles, or the failure of a similar scheme in Holland, or the fact that most disturbances were outside grounds rather than inside - let alone the wider civil rights issues.

It would take a tragedy of dreadful proportions, and its subsequent landmark report, to see the unloved scheme reluctantly ditched.

Hillsborough

Hillsborough was the final, horrific act in a trio of devastating sporting disasters during the Thatcher era.

Margaret Thatcher visited the Leppings Lane terrace at Sheffield Wednesday's ground the day after 96 Liverpool fans were crushed to death

In May 1985, 56 spectators lost their lives in the fire at Bradford City's Valley Parade stadium; three weeks later, 39 spectators died at the European Cup final between Liverpool and Juventus in Brussels' Heysel Stadium.

Thatcher visited the Leppings Lane terrace at Sheffield Wednesday's ground the day after 96 Liverpool fans were crushed to death. Disclosures last year under the Freedom of Information Act revealed that she was told by senior police officers that the catalyst for the tragedy was drunken, ticketless Liverpool fans.

It would take over two decades for that malicious lie to be exposed. Thatcher, a staunch and unwavering supporter of the police, would never publically challenge it.

Among the new documents released last year was a memo from a senior civil servant about the interim report into the tragedy by Lord Justice Taylor.

Thatcher was told the August 1989 report had found that the chief superintendent in charge at Hillsborough had "behaved in an indecisive fashion" and senior officers had infuriated the judge by seeking to "duck all responsibility when giving evidence" to his inquiry.

The memo made it clear that former Home Secretary Douglas Hurd thought South Yorkshire Chief Constable Peter Wright would have to resign, and stated: "The defensive, and at times close to deceitful, behaviour by the senior officers in South Yorkshire sounds depressingly familiar. Too many senior policemen seem to lack the capacity or character to perceive and admit faults in their organisation."

The report, the memo added, would "sap confidence in the police force" and could encourage aggressive behaviour by fans who would feel "vindicated" by its conclusions.

In a handwritten note, Mrs Thatcher made it clear that she did not want to give the government's full backing to Lord Taylor's criticisms, only to the way in which he had conducted his inquiry and made recommendations for action.

She wrote: "What do we mean by 'welcoming the broad thrust of the report'? The broad thrust is devastating criticism of the police. Is that for us to welcome? Surely we welcome the thoroughness of the report and its recommendations."

Thatcher was not the only establishment figure to accept the blatant falsehoods spread by the South Yorkshire and Merseyside forces. But her intransigence was repeatedly criticised by the three Hillsborough support groups, and obliquely referenced by Prime Minister David Cameron in the aftermath of the Hillsborough Independent Panel's findings last year.

Mr Cameron said: "At the time of the Taylor Report the then prime minister was briefed by her private secretary that the defensive and - I quote - 'close to deceitful' behaviour of senior South Yorkshire officers was 'depressingly familiar'.

"And it is clear that the then government thought it right that the chief constable of South Yorkshire should resign. But... governments then and since have simply not done enough to challenge publicly the unjust and untrue narrative that sought to blame the fans."

School sport

Thatcher's 1981 Regulation 909 gave education authorities the right to sell school land that they considered surplus to their requirements.

Over the next decade an estimated 5,000 playing fields were sold, many converted to housing developments, supermarkets or car parks.

When a prolonged industrial dispute between government and teaching unions, centred on pay and conditions, led to thousands of teachers refusing to continue providing unpaid after-school sports lessons, pupils' hours of sports fell still further.

Thatcher's supporters would blame instead a decline in competitive sports. Other, wider forces were also at work - the rise of computer gaming, a society-wide increase in sedentary lifestyles.

Whatever the cause, a survey by the Secondary Heads Association showed that the proportion of pupils under 14 spending less than two hours a week in physical education rose from 38% to 71% between 1987 and 1990.

By the end of the Conservative hegemony in 1997, that figure had crept above 75%.

1986 Commonwealth Games

As Prime Minister, Thatcher strongly opposed economic sanctions against South Africa's apartheid regime.

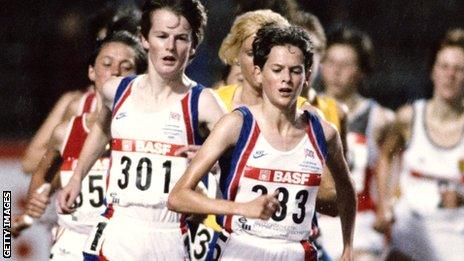

In 1984, Thatcher's government granted teenage runner Zola Budd (centre), from apartheid-era South Africa, a controversial British passport.

In 1984 the government granted teenage runner Zola Budd (centre), from apartheid-era South Africa, a controversial British passport

Her controversial stance of "constructive engagement" was one shared by US President Ronald Reagan but not the majority of Commonwealth countries.

When she re-stated her position in the weeks leading up to the Edinburgh Games of 1986, a boycott began to build, led first by Nigeria but eventually joined by 31 other countries - more than half the number eligible to take part.

The Games, already stricken by financial woes, were reduced to a shell. Only 1,662 athletes competed - less than at any staging since 1950.

It was still a year before Thatcher would refer to the African National Congress (ANC), which began armed struggle against the apartheid-era South African government in 1961 and for whom imprisoned member and future president Nelson Mandela was a rallying point, as "a typical terrorist organisation".

But her bullish stance was already clear.

In 1984, with South African sportspeople under a UN-sponsored ban, teenage track sensation Zola Budd was granted a British passport just 12 days after flying in from Cape Town.

The 17-year-old had bettered the world record while in South Africa but her mark went unrecognised as a result of her home nation's exile.

A British grandfather was unearthed in the family tree and, although she finished seventh after clashing with home favourite Mary Decker in the Los Angeles Olympics of 1984, Budd went on to win two world cross country crowns for her new country.

However controversy dogged the famously bare-footed Budd's every step. Her early appearances were disrupted by protests from anti-apartheid protesters, which Thatcher described as "utterly appalling".

"We have lost the finest Captain of Team GB," said Lord Moynihan, in the hours after Thatcher's death on Monday. As in politics, not all in sport would agree.

- Published9 April 2013

- Published9 April 2013

- Published9 April 2013

- Published9 April 2013

- Attribution

- Published9 April 2013

- Attribution

- Published9 April 2013

- Attribution

- Published8 April 2013

- Attribution

- Published9 April 2013