Martin Ling: Depression should not stop managers

- Published

A nervous breakdown at a service station, a stint in the Priory and out of work. All within three months.

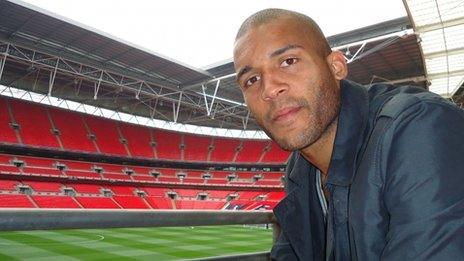

Former Torquay United manager Martin Ling was sick. Now he is better, but not back in the game.

"I see depression as a coffee stain I need to get past. And it may take a brave person to re-employ me," Ling told BBC Sport.

"There is still a stigma in and around depression. Five years ago, if a player came to me with it, I may have seen it as a weakness within him.

"If you're the man in charge at a club, you can't be seen to show any weakness. Players and fans will try and work on it."

In February last year, Ling dropped out of the game, taking time away from his Plainmoor job because of what was described as a "debilitating" illness.

Cue the rumours. Brain tumour? Cancer? Alcoholism?

Twelve months later, with support from the League Managers' Association (LMA),, external Ling has decided to talk about suffering with depression, and at the same time put to rest the mystery behind his disappearance.

An east London boy with cheek and charm in equal measure who went on to run the wing for Swindon, Leyton Orient, Southend and Exeter, Ling had already dealt with the pressures of playing in the Premier League and then management before the illness took hold.

Having led Orient to promotion in 2006, it was in his second job at Cambridge United, external that the first signs of a problem arose.

The impact was brief. And the touch paper? A tub of hair gel.

"The party line at Cambridge was it was a virus," he said.

"We were at Rushden the week before. I had never gelled my hair before I left the house.

"I went to a service station at Rushden, got some gel.

"But when I got to the dressing room I felt not right, like I was having an out-of-body experience. I was sweating, getting het up about the game. Everything little seemed so big."

Ling was put in touch, through the LMA, with a therapist and, with cognitive behavioural therapy and medication, he was back at work without anyone at the club any the wiser.

But the second time, more than three years later, a day before his Torquay side were to face local rivals Exeter, Ling started to unravel.

Convinced he had a brain tumour, he was taken to hospital for tests. Nothing.

"I knew I wasn't ill. But deep down I was hoping they would find something, because I didn't want it to be depression again," he said

"The next day I was driving on the M5 and just before Taunton services I was struggling to hold the wheel. I'm thinking 'I'm having a heart attack now'.

"So I go into the services and say to the woman there 'I'm dying from a heart attack'.

"The ambulance people guaranteed me I wasn't having a heart attack, I was having an anxiety attack.

"I said 'I'm going to get you sacked, because I'm having a heart attack'. My assistant Shaun Taylor had to scoop me off the M5."

A phone call from Ling's wife to the LMA saw him in the Priory - the elite mental health facility in Roehampton associated with celebrity addiction recoveries - within two days.

Paid for by the LMA, Ling acknowledges he received treatment beyond the means of the common man.

"At the start, the medication in the Priory was heavy. You feel like you've got two heads. You want to isolate," he explained.

"Your day consisted of therapy - coping strategies, music therapy, yoga, art. I was sitting there doing art. You're thinking 'how is art going to help me?'

"But you're drawing a picture and it tells you something about what's coming out of your brain.

"I fully feel now I've got the tools to cope."

Torquay insist he was sacked in April last year for footballing reasons, something Ling queries, having reached the League Two play-offs the season before.

Ling is not short of work, doing radio commentary, setting up a coaching school for youngsters and scouting for friend and Walsall boss Dean Smith.

But none of those are the job he wants - to be back managing a football club.

"It doesn't say on my CV that I've got depression. I've only had two interviews and not got either of those jobs," he explained.

"Whether that's because of depression or somebody was more qualified - that's not my decision.

"I've even said if I had to leave for non-footballing reasons, they wouldn't have to pay me. I've offered my services without that safety net."

tqy lko

Examples of sportspeople talking about their battles with depression are not widespread but they are becoming more and more common.

Celtic manager Neil Lennon remains one of the most high profile from the world of football, but few will speak of their demons while they still rattle around in the context of testosterone-ridden, banter-drenched changing rooms.

"Men will hide it more than women. There's a stigma that you're big and brutish and shouldn't break down," Ling concedes.

"When you can see something is damaged on the outside, you feel sorry for that person. But when it's your brain, it's seen as a weakness. But one in four people will suffer from it.

"You can recover from cancer. You can recover from a brain tumour. And you can recover from depression."

Should it be surprising that an industry where millions of pounds are at stake, and managers can be mutually consented out of the door at a moment's notice, has a system to deal with the affects of mental health?

When Ling was put through that system, he had messages of support from Sir Alex Ferguson, Sam Allardyce and Chris Hughton. The structure of football already knew how to react, the machinery was already in place.

Ling was not the first. He will not be the last.

"When I spoke to an independent therapist who worked for the LMA, I put two and two together and knew that there had been previous people. I'm no idiot," he said.

"I wasn't the first person that had been put through that system. The LMA knew the avenues to send me down."

There is a question that hangs in the air though, waiting to be asked.

Why would a man, who has endured depression, want to still be a football manager?

The cockney chirp and relaxed demeanour subside, ever so briefly.

"Are you telling me the dustman or the builder doesn't have the same pressures of putting food on the table?

"Should a person recovering from cancer or a brain tumour be allowed to manage?

"The answer is yes.

"Should someone who has recovered from depression be allowed to manage?

"Of course he should."

- Published9 July 2013

- Published9 October 2013

- Published29 April 2013

- Published7 June 2019