Depression and suicide: Football's secret uncovered

- Published

- comments

Everyone else thought I'd made it, that I had the dream life. And I did.

I was a 21-year-old professional footballer for QPR and the England Under-21s. I had a nice flat, a nice car and a loving family.

My irrational mind had made me think suicide was a rational action though.

So I went to a park near my home in Acton armed with lots of painkillers and thought "I'm going to take all these pills and kill myself, because I'm no use to anyone".

I'd just suffered a severe knee injury and had convinced myself that without football people would see me for what I really was, which was nothing.

I sat on a bench in that park, washed the pills down with a can of beer, and waited for it to happen. In the end I was incredibly lucky, because my girlfriend found me and I was rushed to hospital in time to have my stomach pumped.

I survived and didn't tell another soul about the incident for years and didn't ask for any help. I just locked this suicide attempt away in Pandora's box., external

I go back to this spot in my BBC Three documentary, Football's Suicide Secret.

As you'll see, it was horrible to go back there, I couldn't stand it. It was awful to think something so strong could have come over me to make me lose sight of all the good in my life.

I thought about what I could have missed out on - the great relationship with my daughter, meeting my wife - and I was so ashamed.

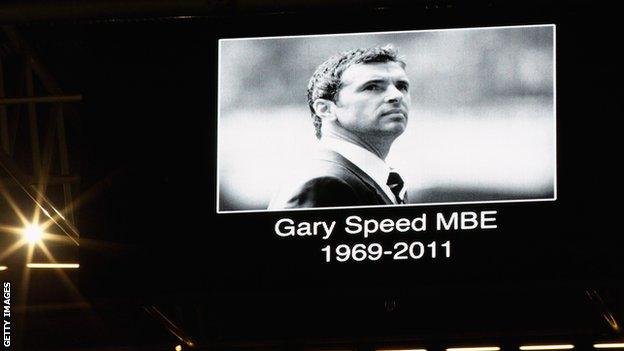

That's why speaking to Gary Speed's sister Lesley was such a profound moment, an epiphany in fact. Speaking to her made me see what I could have put my own family through.

I saw the butterfly effect,, external how the lives of Gary's parents, children, wife, neighbours and the wider football community were all traumatised by his decision to take his own life.

It's the first time Lesley has spoken publicly about Gary's death. She says that if someone had asked her whether Gary was suffering from depression before that, she would have said absolutely not.

"He hid it from us and it stopped him asking for help," she tells me. Yet still she regrets not having been able to help him. "We were just so sad that we couldn't help him through," she says. "That's a huge regret that I didn't get him to one side and say 'is everything alright?'"

I know only too well that most depressives are great actors who can put on a different persona, a facade. What you need to be able to do is open up, yet the cruelty of the illness is that it won't let you.

Working on the documentary was very cathartic. I spoke to other professional footballers who have suffered in silence with depression, and I now believe there are hundreds of pros and ex-pros who are suffering from the illness, even though they might not know it.

I spoke to former Aston Villa and England midfielder Lee Hendrie, who was earning £40,000 a week and owned £10m worth of properties at the peak of his career. "I thought this is it, this is where I want to be," he tells me.

Yet his life unravelled when he was declared bankrupt after defaulting on a number of mortgages.

"I felt like the whole world had fallen down on top of me and said to myself 'I cannot go on,'" he says.

Germany have put impressive measures in place following the suicide of German international Robert Enke

Twice he took overdoses of sleeping pills but, like me, was found and survived. "To be there and feel that massive drop to the bottom was horrible," he says.

Former Norwich striker Leon McKenzie also tried to kill himself after a serious injury coincided with the the breakdown of his marriage and family.

As chairman of the Professional Footballers' Association,, external I was shocked to hear that Leon had phoned my organisation to talk about his depression yet had not been given an understanding response.

It was very telling that neither Lee nor Leon felt they could talk to anyone about their problems.

I didn't actually realise I was depressive until a few years ago, when my wife was diagnosed with post-natal depression. I'd told her to 'get a grip' and reminded her that we had a great house, great car, lovely kids etc etc.

Then I was told about Goldberg's depression test., external I looked at the checklist and soon understood what she was going through. I also realised 'that's me'. When I took the test, the result came through that I was suffering from severe depression.

Former Norwich striker Leon McKenzie has rebuilt his life and taken up a career in boxing

Suddenly this realisation made sense of a lot of things I'd done in my life and drove me to find out as much as I could about the illness. As chairman of the PFA I also felt a sense of responsibility to help my fellow pros.

I have a very strong body, yet it can still break down, and the mind is the same. Depression is a mental injury that needs diagnosing and treating.

You've got to find the triggers, analyse them and then reduce the chances of a depressive episode. If people are educated about depression, they have a better chance of understanding the triggers, spotting the signs of depression and doing something about it - whether in themselves or others.

They can stop the slide by having a conversation and then seeking out counselling. It's all about knowledge and education.

We need forensic research about the potential triggers for depression. For example when a player retires, his chances of getting clinical depression go up 40%. Other common triggers are injury, being transferred, the inability to separate home and work life. Yet I must also point out that there is often no logical trigger because depression is an indiscriminate illness.

I travelled to Germany and was very impressed by the mechanisms they have in place to tackle depression following the suicide of Robert Enke in 2009., external Every professional club has access to psychiatric treatment, there is a 24-hour hotline for players who think they might be suffering from depression and the Robert Enke Foundation, external tries to raise awareness of mental illness.

The situation in this country needs to catch up fast. Suicide is the biggest killer of young men of 18 to 35, external and I firmly believe the majority can be prevented.

As part of the programme I took all my findings to FA chairman David Bernstein and said "what are you going to do?" He admitted the issue had been neglected and said he wants to tackle the stigma surrounding mental health issues because "the very nature of the problem is that it tends to be kept quiet".

Football needs to tackle this in a co-ordinated way and I'm determined to help make that happen.

Watch Football's Suicide Secret on BBC iPlayer now.

Clarke Carlisle was talking to BBC Sport's Simon Austin.

- Published23 May 2013

- Published16 March 2013

- Published20 June 2013

- Attribution

- Published27 November 2011

- Attribution

- Published27 November 2012