How can football tackle the social media hate merchants?

- Published

Yaya Toure was abused soon after returning to Twitter

Many observers were encouraged to see Manchester City midfielder Yaya Toure speak out via the BBC last week against those who had racially abused him over Twitter just hours after he had reactivated his account.

As one of the sport's most high-profile figures, it felt as if the Ivory Coast international had made a stand on behalf of an ever-growing number of similar victims in the game - because Toure is far from alone in being subject to such treatment.

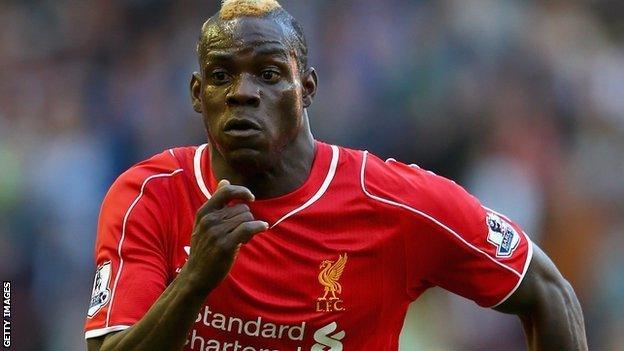

Already this season, Liverpool striker Mario Balotelli has been racially abused over the internet after he made fun of Manchester United following their defeat to Leicester City.

Last year I interviewed former footballer and Professional Footballers' Association (PFA) chairman Clarke Carlisle at his house.

He showed me his laptop and the torrent of vile racial abuse he had received via Twitter, abuse he did not want his wife or children to see, and which had left him feeling numb.

And all because he had been commentating on a match that week on TV.

Last season, 50% of all complaints about football-related hate crime submitted to anti-discrimination organisation Kick It Out (KIO) related to social media abuse.

So severe is the problem, KIO now employs a full-time reporting officer whose job is to act on such incidents and refer them to the relevant authorities.

Greater Manchester Police are investigating the Toure case, but don't be too surprised if no-one is ever punished.

The anonymity users can gain on social media can make it very difficult to track down offenders.

Frustration

But Kick It Out is also frustrated by what it feels is a lack of a co-ordination between the police and Twitter and the need for better communication between the two.

It feels there needs to be more education for local police forces on the misuse of social media and how complaints are dealt with.

In some cases, KIO says, it has made a report but has not heard back from the police, something one source there described as "very disheartening".

Balotelli was abused after he made fun of Manchester United

In addition, KIO wants more clubs to be proactive in coming out to publicly support their players when they are the victims of discrimination online, by calling upon the authorities to work closely with the relevant platform to investigate and track down the offenders.

Such concerns are nothing new.

Accounts with false identities often mean the police need Twitter to provide them with an IP address for the account if they hope to find them.

The Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) has said that Twitter only provides this information with a US court order, something which it is difficult to get because of the value and protection afforded there to freedom of speech.

Elsewhere - like in the UK - it is optional, although Twitter insists it is co-operating with law enforcement here more than ever before.

Little wonder perhaps, that last year former footballer turned boxer Curtis Woodhouse took matters into his own hands, tracking down an internet troll that had been abusing him on Twitter for months, and confronting him on his doorstep.

Former footballer Stan Collymore has accused Twitter of inaction over a torrent of racist abuse and death threats he received from internet trolls.

Staffordshire Police said it had had to drop an investigation into the abuse against the former England player after Twitter had refused to hand over information about the offenders despite "repeated requests".

Twitter contradicted the force's account and said it had cooperated with police but officers had "stopped responding to our requests for additional legal clarification".

The site points out that targeted abuse is against its rules and that it has recently made it easier for users to report abusive messages, along with established processes in place for working with law enforcement.

How Twitter tackles abuse |

|---|

Over the past year it has expanded the number of people working on abuse reports, reporting 24/7 cover.It has invested in technology to make it harder for serial abusers to create accounts, and perpetuate abusive behaviour.It has worked with the Safer Internet Centre and charities that specialise in developing strategies to counter hate speech. |

During the first half of 2014, Twitter received 78 account information requests, 46% of which resulted in some information being produced, the highest proportion to date.

It says it has made it easier for users to report malicious posts, claims it has become more vigilant in blocking offensive tweeters, and is developing technology that prevents barred trolls from simply opening up a new account.

Progress being made

The police insist important progress is being made, and that platforms are now beginning to appreciate the responsibility they have for what is posted on their networks.

Last year, following a long legal battle in France when prosecutors argued Twitter had a duty to expose wrong-doers, the site agreed to hand over details of people who allegedly posted racist and anti-Semitic abuse.

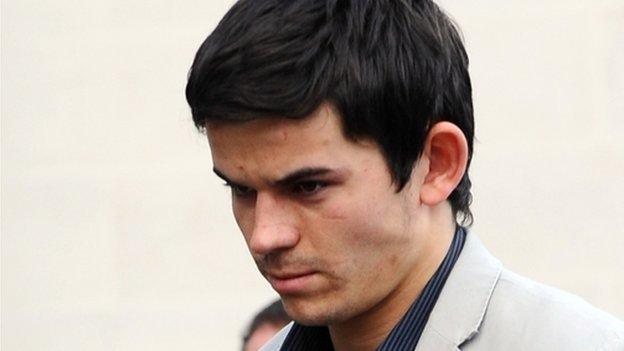

Liam Stacey was jailed for abusing Fabrice Muamba on Twitter

Although that set an important precedent, Twitter admits it could do better.

Earlier this year it promised to change its policies after Robin Williams's daughter Zelda was targeted by trolls following his suicide.

But there are signs that such abuse will not be tolerated.

In 2012 Liam Stacey, from Swansea, received a prison sentence after racially abusing former Bolton player Fabrice Muamba on Twitter.

Last year, a man who admitted sending racist tweets to two footballers was ordered to pay £500 compensation to each of them. And police were heartened last month when a Nazi sympathiser was jailed for four weeks for sending anti-Semitic tweets to Jewish MP Luciana Berger.

But these cases, of course, while dissuading some, will not prevent further incidents from occurring. Twitter admits it is impossible to monitor all of the 500 million or so postings going through its networks each and every day.

One expert I spoke to told me that some of the cases the UK media has picked up on would simply not register in the US, where such abuse is often disregarded and denied the publicity some trolls crave.

Others will insist that it is absolutely right that such vitriol is exposed and condemned.

Paul Giannasi, hate crime lead officer at ACPO, said the challenge was huge, but efforts to combat the problem were constantly evolving. ACPO sits on an international cyber-hate working group lead by the US based Anti-Defamation League. This group brings parliamentarians, professionals and community groups together with industry leaders to help find solutions that balance protection from offensive comments with the right to free speech.

"The police will draw on the guidelines issued by the Director of Public Prosecutions and The College of Policing to assess whether the threshold for communications which are grossly offensive, indecent, obscene or false is met.

"The CPS guidance is very clear that a high threshold applies in these cases. We encourage officers to work with the CPS at an early stage of an investigation to determine whether proceeding with a prosecution is in the public interest."

Certainly, with its tradition of rivalry and tribal passions, football seems particularly vulnerable to the dark side of social media.

Twitter and other platforms have enabled fans and the players they idolise to get closer than ever.

Amid the anodyne world of bland footballer interviews, it is refreshing that players' true emotions and opinions can often be glimpsed online even if sometimes it results in them being fined.

But it also enables a sad and cowardly minority to abuse and insult in a way that would never be tolerated - and that they would never dare to - in a public, physical place.

Amid unprecedented interest and media exposure, footballers can be followed by millions of supporters.

This makes them an attractive target for the trolls who crave attention through a retweet, and seek maximum impact from their messages of hate.

The question is how to tackle them without endangering the freedom that makes social media such a special place to so many.