Democracy in sport: An uneasy relationship with politics

- Published

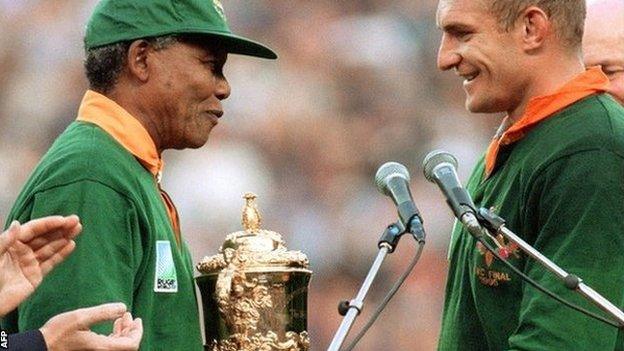

Nelson Mandela's support of the South African rugby team was thought to help galvanise the "rainbow nation"

"Less democracy is sometimes better for organising a World Cup."

The words of Fifa secretary-general Jerome Valcke in the fraught build-up to Brazil 2014 may have surprised some people, but they serve as a reminder that sport's relationship with democracy is an uneasy one.

Formula 1 supremo Bernie Ecclestone is another powerful sporting figure who has made no secret of his preference for totalitarianism.

The billionaire provoked outrage in 2009 when he spoke of his admiration for Adolf Hitler, external for "getting things done".

And yet, ever since ancient Greece, the birthplace of both democracy and the Olympics, sport and self-rule have had a close relationship.

As Professor Paul Christesen points out in his book Sport and Democracy in the Ancient and Modern Worlds, there was a correlation between the advent of mass sports participation on the playing fields of 19th Century Britain and the granting of political rights to the middle class.

Self-governed "horizontal sport", as Christesen puts it, promotes the concept of teams and clubs, levelling social relations between people and acting as a force against discrimination.

At a fundamental level, sport can help us to trust others, encouraging us to adhere to rules without the need for excessive coercion.

Free societies cannot be too controlling of course, so sport's requirement for participants to be willing to stay within the rules can have a strong democratising effect.

Powerful tool

Sport does not necessarily equal democracy, however.

The spectacular Beijing Olympics did not precipitate huge change in China

The regimented gymnastic displays seen in North Korea and Nazi Germany, where sport was very important, reflect an authoritarian political system while doing nothing to bring about reform.

The recent protests in Hong Kong are evidence that when it comes to democracy, the 2008 Olympic Games in Beijing did not achieve anything like as much as many had hoped.

But sport has proven to be an incredibly powerful force for change.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC)'s exclusion of South Africa from the Olympic movement in 1970, along with cricket and rugby boycotts, helped to bring about the end of apartheid.

The 1988 Seoul Olympics are widely credited with sparking the demonstrations that resulted in the downfall of South Korean dictator Chun Doo Hwan.

However, although sport may help to shine a light on repressive regimes, it has also been exploited.

Propaganda potential

Ever since Hitler's 1936 Olympics in Berlin, dictatorships have used competitive events as a form of propaganda, diverting attention from some of their less appealing activities.

Jesse Owens's success dented Hitler's attempt to use the Berlin Games for propaganda purposes

Even now, in the 21st Century, more and more sports events seem to be hosted by authoritarian states, using them to gain political legitimacy and strengthen the power and profile of their rulers.

Where once sports turned to Western democracies as the natural place to do business, they increasingly look east, to countries where money, rather than freedom, rules.

Thanks to its vast wealth, the Arab world is becoming a true sporting hub. Dubai and Abu Dhabi, in particular, are hosting more global events, sponsoring shirts and stadia, and buying up sporting assets. By doing so, they gain exposure, improve their image, and accumulate "soft power" among their trading partners and military allies in the Western world.

No matter that Amnesty International says the United Arab Emirates is a "deeply repressive state", a recent report pointing to "a climate of fear, with authorities going to extreme lengths to stamp out any sign of dissent".

This summer, Azerbaijan will host the first European Olympics, despite ranking 156th out of 179 in the Reporters Without Borders world press freedom index, "a template lesson in how to launder a country's image through sport", according to Amnesty.

Despite grave concerns over its human rights record, the country's capital, Baku, will also stage an F1 race in 2016 and host matches in the Uefa 2020 European championship finals.

Hosts of both the 2014 Sochi Winter Games and the 2018 World Cup, Russia is staging more international tournaments and competitions over the next few years than any other nation in the world, despite controversy over a crackdown on freedom of speech and expression.

Human rights violations

Last year, Amnesty demanded the IOC take Russia's leadership to task over a "blatant violation of human rights" in the context of the 2014 Games.

"Its failure to admonish the authorities for their ongoing harassment is a failure to live up to the very principles that form the core of the Olympic Charter," Amnesty said.

After being left with a choice between cities in two repressive states, external - Beijing and Almaty, Kazakhstan, - as host of the 2022 Winter Olympics, the IOC has now passed a raft of reforms designed to entice more democratic countries to bid for such events.

For the first time, human rights protections will be included in host city contracts.

"For years repressive governments have brazenly broken the Olympic Charter and the promises they made to host the Olympics," said Minky Worden, director of global initiatives at Human Rights Watch.

"This reform should give teeth to the lofty Olympic language that sport can be 'a force for good'."

But as well as being accused of turning a blind eye to human rights violations, sport can even find itself responsible for them.

Fifa has been admonished for its decision to give the 2022 World Cup to Qatar,, external where the abuse of migrant workers building the infrastructure for the tournament continues to cause concern.

Critics also point to the violent response of the Brazilian police to anti-World Cup protesters in the run up to the tournament there last year.

F1 has been blamed for crackdowns in Bahrain whenever grands prix take place on the troubled island kingdom.

Soviet Union performance in Summer Olympic Games |

|---|

1952, Helsinki - Gold 22, Silver 30, Bronze 19 - Second place |

1956, Melbourne - Gold 37, Silver 29, Bronze 32 - First place |

1960, Rome - Gold 43, Silver 29, Bronze 31 - First place |

1964, Tokyo - Gold 30, Silver 31, Bronze 35 - Second place |

1968, Mexico City - Gold 29, Silver 32, Bronze 30 - Second place |

1972, Munich - Gold 50, Silver 27, Bronze 22 - First place |

1976, Montreal - Gold 49, Silver 41, Bronze 35 - First place |

1980, Moscow - Gold 80, Silver 69, Bronze 49 - First place |

1988, Seoul - Gold 55, Silver 31, Bronze 46 - First place |

But should we really be surprised?

Play the Game,, external an initiative aiming to promote transparency and freedom of expression, argues there is little democracy in sport.

Its Global Sports Political Power Index of international sports organisations found only four out of 16 federations published an externally audited financial report and only two had an athletes' commission.

From Fifa president Sepp Blatter to Bernie Ecclestone, sport is no stranger to dictatorial rule.

Scandals over integrity litter the sporting landscape.

The world governing bodies of athletics, football and cycling are all currently struggling to tackle allegations of corruption and cheating.

Repressive regimes have certainly looked to exploit sport for their own political ends.

During the Cold War, Communist countries wanted to use Olympic medals as a means of proving the superiority of their ideology over capitalism.

State-sponsored sport

With greater state control of the population, a more industrial approach to the production of athletes was possible, with talented youngsters hot-housed in dedicated training bases by target-driven coaches in a way seen as too intense in many Western cultures.

State-sponsored sport became a key priority for East Germany, which despite a population of fewer than 17 million people, used a highly organised sports programme - and systematic, state-sponsored doping - to became an Olympic phenomenon during the five summer Olympic Games in which it competed, second only to the USSR in 1976, 1980 and 1988.

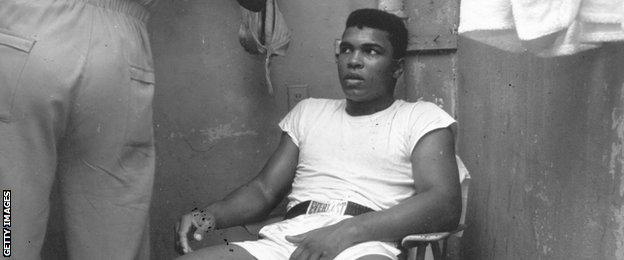

Muhammad Ali was stripped of his world heavyweight title for refusing the Vietnam draft

Over the course of its nine summer Games, the Soviet Union topped the medal table six times, averaging 112 medals per Games, more than the USA, where professional, commercial major-league sports such as American football, baseball and basketball took priority.

Thanks to Soviet help in training its athletes, Communist Cuba, with a population of just 10 million people, also finished in the top 10 of the medal table in the five summer Games it competed in between 1976 and 2000 (they boycotted 1984 and 1988).

After the end of the Cold War, many Soviet coaches found employment in China, which began a remarkable nationwide push towards sporting success as a means of healing wounds left by the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre and to improve its image abroad and its chances of bidding to stage the Games themselves.

Having won just five golds in 1988, China's programme paid off dramatically, winning 10 times that number in 2008, topping the medals table in its own Beijing Games, and establishing itself as the Olympic powerhouse of the 21st Century.

But what role does sport play in democracies?

We are often told here that sport and politics should not mix, that politicians should not meddle with sport, and most sports organisations actively discourage governments from encroaching on their territory.

The prime minister spoke out on the divisive argument around convicted rapist footballer Ched Evans, but was careful to avoid telling the FA what to do about it.

Many were surprised last year, when Sports Minister Helen Grant dared criticise the Premier League over rising ticket prices.

But as the tit-for-tat boycotts of the Olympic Games in the 1980s proved, sport operates in the real world.

And when it comes to the furthering of political causes, sport has often shown itself to be more powerful than elected representatives.

Inspirational actions

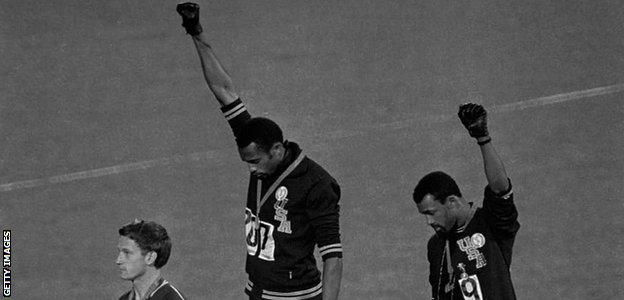

The Mexico Olympics black power salute created worldwide headlines

One need only think of Jesse Owens's four gold medals, external in Berlin in 1936, shattering Hitler's plan to use his Olympics to demonstrate the superiority of the Aryan "master race" or Muhammad Ali's opposition to the Vietnam War by refusing the draft.

The raised, clenched fists of John Carlos and Tommie Smith as they gave the Black Power salute on the podium during the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City remains one of the enduring images of sporting history.

As does Nelson Mandela wearing the Springbok rugby jersey, that emblem of white rule, as he presented South African captain Francois Pienaar the Rugby World Cup in 1995., external

For all their fame and fortune, sportsmen and women now seems less willing to be political.

Perhaps the financial fortunes at stake make them nervous about offering up opinions in case they upset anyone.

"Athletes today tend to be so focused in their own bubbles, the world passes them by," says Professor Alan Bairner, of Loughborough University.

"These days, there are few socially concerned sportspeople.

"Even during the Commonwealth Games in Glasgow, there seemed to be a truce called ahead of the vote on independence.

"There was pressure not to politicise it.

"Scottish athletes were reluctant to say how they felt."

From Liverpool striker Robbie Fowler expressing his support for striking dockers, external to NFL stars backing the Ferguson rioters, there are exceptions.

Moeen Ali was banned from wearing wristbands with a political message

But sport seems increasingly nervous about overt displays of political opinion.

England cricketer Moeen Ali wore "Save Gaza" and "Free Palestine" wristbands during a Test match against India in 2014.

But he was quickly banned from doing so by the International Cricket Council, on the basis that the rules "do not permit the display of messages that relate to political, religious or racial activities or causes during an international match".

Having tweeted his support for the Yes campaign on the morning of the referendum on Scottish independence, tennis player Andy Murray received a torrent of abuse via social media and quickly expressed his regret at having revealed his opinion.

Uneasy mix

Sport and politics remain uneasy bedfellows.

Politicians may like to associate themselves with successful sportspeople and events, but democracy is rarely influenced by them.

Back in 1970, the outcome of the general election itself may have been swayed by a sporting result - Edward Heath's Conservatives pulling off a surprise victory in a poll that many believe was influenced by England's shock defeat to West Germany, external in the 1970 World Cup a few days before.

Local Government Minister Tony Crosland famously blamed Labour's defeat on "the disgruntled Match of the Day millions".

Forty-five years on, sports issues will play a much less decisive role in the forthcoming 2015 poll.

There will be some interest in how the parties intend to make the country more active at a time of rising childhood obesity, three years on from the London Olympics.

But it is the economy, the NHS and immigration that will determine how we all vote.

However, the place of sport in society, whether democratic or otherwise, remains significant. Sport and politics simply cannot escape each other.

They remain as interlinked as the Olympic rings themselves.

BBC Democracy Day

Democracy Day takes place on Tuesday 20 January, across BBC radio, TV and online

A look at democracy past and present, encouraging debate on its role and future

2015 marks the 750th anniversary of the first parliament of elected representatives at Westminster

It also sees the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta - a touchstone for democracy worldwide

Go to the BBC News website's Democracy Day page, external, for analysis, backgrounders and explainers on the debate

- Published20 January 2015

- Published20 January 2015

- Published20 January 2015