How Formula 1 is going green for 2014

- Published

Formula 1 enters a brave new world in 2014, embracing energy efficiency through a new engine design, changes to the cars and a fuel limit.

But the new rules, which aim to reduce fuel consumption by 35%, have so far had a bumpy ride.

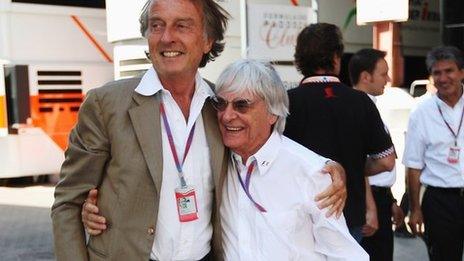

A plan to switch from the current 2.4-litre V8s to 1.6-litre turbo-charged V6s is going ahead despite the vocal opposition of F1 boss Bernie Ecclestone - but not before the original plans for four-cylinder engines were revised to soothe Ferrari's objections.

Likewise, a proposal to alter fundamentally the philosophy by which cars are designed was abandoned after teams said they could achieve the same efficiency gains with tweaks to the current rules, reducing both costs and the risk of the new rules being a mistake.

So, straight fours became V6s and a major change to car aerodynamics was abandoned - that was already two big changes to the original plans for a new 'green' F1.

Then, on Wednesday, F1's governing body the FIA put out a statement saying: "Changes made to bodywork design, originally aimed at reducing drag and downforce for increased efficiency, have reverted to 2012 specification."

Was this another change of tack? Was the much-vaunted 'green' F1 being abandoned? Had Ecclestone quietly won another political battle with FIA president Jean Todt?

Well, no, as it turns out.

The choice of wording was perhaps a touch misleading, but it refers to ongoing attempts to ensure the new rules meet their original targets - which were to ensure the new cars in 2014 are no more than five seconds slower than they were in 2010 as well as being much more efficient.

As the teams began work on the new designs, simulating the car layouts and projected engine performance, it began to become apparent that lap times might well be slower than had been intended.

So teams were tasked with looking independently at what elements of current car design could be maintained without losing sight of the intent of the new rules to produce aerodynamic downforce with as little trade-off in drag as possible.

The FIA's initial intention had been to strip the cars of all the extraneous bits of curved bodywork that have begun to sprout in various parts of the car, on the assumption that these must be inefficient. But as the effect of these parts was investigated, it turned out they were not as pernicious as at first thought.

So, for example, 'turning vanes' - the curved bits of bodywork that sprout behind the front wheels or under the raised noses - are very efficient. That is, they produce downforce but very little drag.

Likewise, the wide front wings that were introduced as part of the last major rule change in 2009 will stay, albeit they will be a little narrower than they are now.

By contrast, some teams were campaigning to keep what is known as the lower rear beam wing - a downforce-producing device at the bottom of the rear wing where it is attached to the back of the car. But this turned out to be very 'draggy', so it will be dropped as planned.

But the key point is this - the main visual and philosophical changes that were planned for the cars in 2014 have been retained.

So how will they look?

The biggest visible change will be at the front - the high noses that have become de rigueur in recent years will be outlawed.

This is fundamentally for safety reasons - high noses are considered more dangerous when they hit another car because of the increased likelihood of driver injury, and also make it more likely that a car will be launched in an impact. But it will also restrict downforce and make the cars slower.

How much lower will the noses be? In 2012, F1 cars had a maximum front nose height of 550mm above the floor of the car. In 2014, that is being reduced to 185mm - a reduction in height of 365mm.

Likewise, although the wide front wings will stay, they will be reduced in overall width from 1800mm (the same as the maximum width of the car) to 1650mm.

This will almost certainly fundamentally alter the overall aerodynamics of the cars.

Airflow over the car stems from the front wing, as the first part to hit the air. Designers are currently focused on using the ends of the wings to turn air around the outside of the front wheels. But in 2014 there will be 7cm of front wheel outside the wing, so getting the air to go around it will be that much more difficult.

This challenge will be made even harder because of new rules restricting what can be done with the front wing end-plates, the vertical bits at the outside edge of the wing.

Less obviously, but also important in the context of the last couple of years, will be a new rule governing exhaust exits.

Using exhaust gases for aerodynamic effect has become a central feature of F1 car design since 2010.

In 2011, so-called exhaust-blown diffusers, where the exhausts pipes were situated on the rear floor of the car and the engine programmed to blow gases out of them at all times, gained the top teams at least a second a lap.

For 2012, these were banned, engine mapping restricted and exhaust outlets moved forwards on the car and higher up. But teams still managed to use the gases to enhance aerodynamics by directing them at the gap between the floor and the rear wheels using what is known as the 'Coanda' effect.

Red Bull's progress in this area in late September was decisive in Sebastian Vettel beating Ferrari's Fernando Alonso to the drivers' championship.

But for 2014 there will be no more 'Coanda' effect - exhausts will have to exit between 3-5cm forward of the centre line of the rear wheels and no more than 25cm from the centre line of the car. From there, it will be impossible to blow them at the edges of the floor.

Equally, the overall efficiency targets will remain the same - whereas now use of fuel is free, it will be metered from 2014. Currently, cars use about 150kg of fuel (about 195 litres) in a Grand Prix; in 2014, they will be allowed to consume no more than 100kg (130l).

In summary then, the revolution is still very much underway; it's just the fine print that has changed.

- Published6 December 2012

- Published3 December 2012

- Published25 November 2012

- Published26 November 2012

- Published25 November 2012