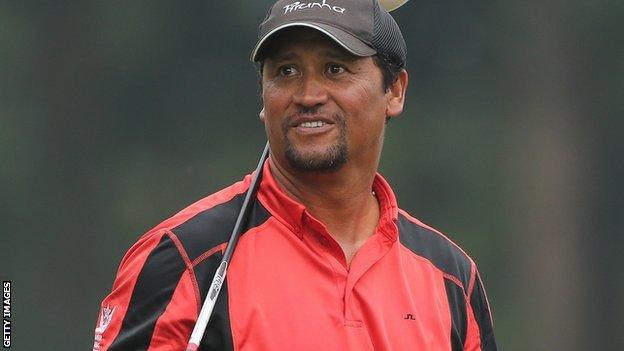

Michael Campbell ready to scale golf's Everest again

- Published

- comments

Sir Steve Redgrave and Michael Campbell are in the back of a courtesy car having just shared a practice round at the Alfred Dunhill Links Championship: British sport's philosopher king dispensing pearls to one of golf's fallen idols.

"I said to Steve: 'Winning a major championship was like conquering Everest. What can I do to better that?' Quick as a flash Steve said: 'Conquer Everest without an oxygen mask.' I thought to myself: 'You clever so-and-so.'"

The date was October 2010 and New Zealander Campbell, the surprise winner of the 2005 US Open,, external was in the midst of a dismal run that saw him make one cut in 19 European Tour events. He retired from two of them and earned about £11,000 for the season.

That June, he was caught up in an etiquette storm at the US Open. Desperate to get off the course after carding 10 bogeys and one double in a second-round 83, Campbell played out of turn on the 18th hole. "This from a US Open champion?" railed the Oakland Tribune., external

The reporter in question had presumably never clung onto something so hard and for so long that his arms were sore and his hands ached, only to watch it fall and shatter into a thousand pieces.

Asked to pinpoint his lowest point, Campbell heaves a deep sigh, the sound of a man casting a bucket down into a well of dark memories. "It was about three years ago," says Campbell, now 43. "I was playing in Doha and I'd missed about 12 cuts in a row. I just thought, 'this is the last straw, I've had enough'.

"So I went back to Australia and took about six months off. It gave me time to reflect on what I should do with my career. Should I give it all up or keep on going? I decided there was still more left in me, so I came back."

The feelings that accompany the disappearance of a talent that made you so vital can only be guessed at. "I felt like I was walking naked, like the grass was taller than me," said Ian Baker-Finch of his opening 92 at the 1997 Open at Royal Troon., external Baker-Finch, winner of the Claret Jug in 1991, cried in the locker room, withdrew from the event and promptly retired from tournament golf.

David Duval, Open champion in 2001,, external turned to his caddie on the flight home from Lytham and said: "I thought it would be better than this." Duval, a former world number one, has not won a PGA Tour tournament since.

Campbell has had plenty of existential moments following his annus mirabilis of 2005, in which he won the World Match Play and finished in the top 10 in the Open and US PGA, as well as winning the US Open at Pinehurst.

"I remember thinking as a kid, 'one day I'm going to hole a putt for a major championship'," says Campbell. "I didn't really look beyond that. So when I won one, I didn't reset my goals. Looking back now is horrible because it was such a simple thing to do. Instead I got totally lost in other things happening off the golf course. It made me forget about the simple things.

"I got lazy because I got so busy with off-the-course stuff, wrapped up with golf course design, appearances, charity days. It was a lot of fun the year after winning the US Open but it ate into my time actually playing golf. I take full responsibility, it was my fault it happened, this whole spiral downwards."

Campbell also remodelled his swing. When it is put to him that this seems like madness, he replies: "Trust me, it is crazy! And it ruined me. But golfers always want to refine, get even better. And how do you get better? You make changes.

"It's like when you buy a car, you don't buy the same car as you bought a couple of years ago, you buy a car that's more advanced. It's a little bit faster, it brakes a little bit quicker, it handles a little bit better. But I made too many big changes to my golf swing rather than little tweaks here and there."

A shoulder injury suffered when lifting a suitcase from an airport carousel - if it doesn't rain, it pours - made things even worse. "It's been traumatic, with lots of things happening around me like a hurricane," says Campbell, who now lives in Marbella, on the Costa del Sol in Spain.

"My wife and family have been through a lot of emotional turmoil, from wonderful highs to awful lows. And it was difficult seeing my family see me like that."

Not that Campbell saw much of his family. Unbowed, he went from country to country, from range to range, emptying thousands of buckets of balls, like an alcoholic trying to find the secret of life at the bottom of a pint jug. Desperate, as his dad put it in a moment of gallows humour, not to go back to being a telephone technician, the job Campbell did before pursuing his dream in golf.

"That was the most difficult part of the whole thing," he says. "When you're not doing well and you're away from your family, you start thinking to yourself: 'Is this worth it? All this hard work for no return? Am I doing the right thing?'

"But you've just got to believe in yourself and things will turn around. Be patient, don't get too upset when things aren't working, keep on plugging away through the dark times."

Rather than dwell on those who faded agonisingly into obscurity, Campbell took heart from those who managed to reverse the trend. Like England's Lee Westwood, who went from being number one in Europe in 2000 to 246th in 2002 and whose advice Campbell cherishes.

And, of course, himself. When profiles of Campbell are written, it is often forgotten that his 2005 wasn't all mirabilis and that he began the season with five missed cuts. "I'm full of surprises," he says.

Last May, Campbell rekindled his partnership with coach Jonathan Yarwood after a three-year break, hired a trainer and got himself fit. Since then, Campbell has had six top-20 finishes, including third at the Portugal Masters last October, his first top-three finish on the European Tour for four years. From 910th in the world last July, Campbell is up to 235th.

"Michael Campbell is back?" he says. "Again?! I feel like The Terminator, I come back every three or four years." Journalistic impartiality suspended, never have I concluded an interview wanting somebody to succeed so much. Keep at it, mate. It's a long way down from Everest, but at least you can see the top again.

- Published29 June 2011