Drug cheats: More sports must follow cycling's lead on blood tests

- Published

- comments

Sport will never win the fight against drug cheats, says John Fahey, president of the World Anti Doping Agency (Wada).

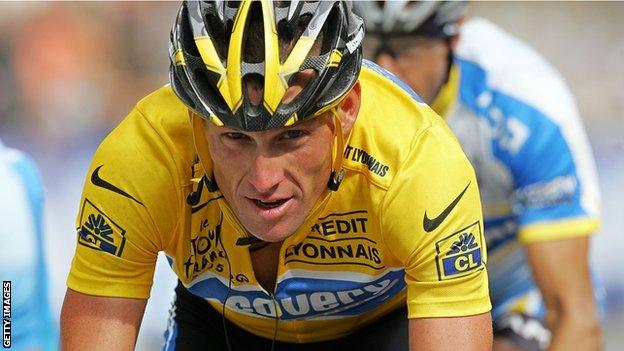

In the post-Lance Armstrong era, trust in sport has never been in shorter supply. Cycling might have lived by its own lawless code for much of the past decade, but deception on that scale has caused us all to pause, reflect and ask ourselves: can we really believe what we are seeing?

In that sense, Fahey's apocalyptic assessment is designed to deliberately exaggerate the scale of the problem. He is, after all, the head of an organisation whose existence relies on the presence of athletes prepared to risk all by taking performance-enhancing drugs. Cops need bad guys.

But it also reflects the growing frustrations with the testing system, highlighted by the way Armstrong and his team-mates flouted the rules. By staying one step ahead of the doping control officers, who had no chance of detecting the sophisticated blood-spinning techniques, they were free to pursue their chemically enhanced careers.

As the outstanding investigation into Armstrong by the United States Anti-Doping Agency (Usada) has demonstrated, testing can only get you so far.

But even the most cursory glance at the statistics for blood testing - the only effective way of checking for blood doping and use of human growth hormone (HGH) and erythropoetin (EPO) - tells you that many sports are simply not operating the sort of system that will help restore trust.

Cycling has got the message. It had no choice. According to Wada statistics for 2011 (the most up to date available), 35% of all drugs tests conducted were blood tests, including the recently introduced blood passport samples, which monitor a cyclist's levels to check for anything suspicious.

Athletics is also pretty good - 17.6% of tests in 2011 were blood tests - but many of the major sports are way behind.

Take tennis. According to Wada figures (which only record tests carried out at Wada-accredited labs) authorities conducted just 3% of their doping control tests on blood last year.

The International Tennis Federation say the real number is nearer 6% because of tests conducted at non-accredited labs. But that is still relatively small and concerns were raised recently by Andy Murray and Roger Federer at the lack of testing.

How does blood doping work?

Neither went so far as to suggest tennis was rife with drugs cheats. Relative to cycling, success is perhaps less reliant on lung-busting endurance, with co-ordination, racquet control and skill a big part of the picture.

That said, Murray and Federer argue more blood tests would be welcome to encourage greater confidence in the sport's top players. And, as anyone who watched the Australian Open final last January knows, this is a sport that is making increasing physical demands on its top players.

It's a similar story in football, where just 3% of tests were blood tests, boxing (3.5%) and gymnastics (1%).

Here's what Fahey, a former Australian politician who fronted Sydney's successful bid for the 2000 Olympics, thinks of that: "We are wasting our time. We are letting people through the loop. We are saying 'you've got an immunity to cheat' if they know there is a very remote likelihood that they'll ever have to give a blood sample.

"That doesn't work for any programme. It doesn't work as a deterrent and it doesn't work to catch the cheats."

During our interview in Paris this month, I asked him whether the low number of blood tests in some sports was a failure of leadership. He replied emphatically: "Yes, I can't argue with that."

So what do sports like tennis and football say?

They argue the cost of blood-testing is prohibitive, the window for collecting and analysing tests small, and the number of substances detected limited. They also say there is little point in using a test for EPO or HGH when all the intelligence and research suggests the problem is not with endurance drugs like those but with other more traditional strength boosters such as testosterone or, in the case of football in particular, recreational drugs.

But it's not like tennis or football, to name just two, are short of a few bob. They could easily afford to use some of the billions of pounds they earn in TV and sponsorship income to increase blood testing.

With the development of more effective tests there is a trend towards more blood tests and the use of biological passports. During the Olympics and Paralympics, around 1,000 of the 6,250 tests conducted used blood samples and Fahey is pushing for all sports to hit a minimum of 10%.

So far there seems to be resistance.

Last week a move by the Wada executive board to get this minimum requirement included in the 2013 update of the Wada code was not adopted. There remains significant opposition to setting such a high threshold.

Carrying out more blood testing might not prevent another Armstrong-like conspiracy but it would at least send a message that sport and its ruling bodies are taking the threat more seriously.

- Published19 November 2012

- Published11 October 2012

- Published4 November 2012

- Published20 April 2012