Olympics & Paralympics: Elite funding plan is bold and ruthless

- Published

- comments

There were two big headlines from UK Sport's "Road to Rio" funding announcement.

The first was the bold ambition to top Team GB and Paralympics GB's roaring success in London by winning even more medals in 2016. The second was the decision to back up that commitment by allocating even more money to elite sport - £347m for the next four years compared with £313m for the four-year build-up to London.

Given the persistent economic gloom, this is no small achievement for British sport.

But in return for the extra money, the government has made it clear no sports will be given a free ride. So out go the smaller sports that only qualified for London - and therefore received seven years' funding - because of Britain's Olympic and Paralympic host status.

That means nothing for handball, basketball, wrestling and table tennis - sports that either failed in London or have no chance of qualifying for the Brazil Games. Volleyball's funding has been slashed - an 88% cut from £3.5m to just £400,000. And even that is just for the women's beach volleyball team.

The message from UK Sport was loud and clear. Those sports that can demonstrate they have a chance of delivering on that ambitious vision of winning more medals will be rewarded.

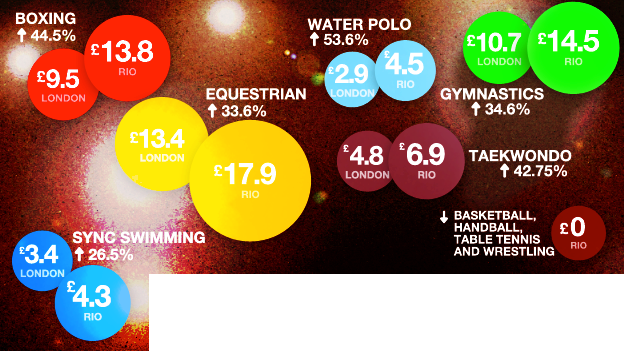

Rowing, already well funded, got a huge increase (up £5.3m) as did cycling (up £4.5m). Of established sports, boxing was the biggest winner in percentage terms, receiving a rise of 44%. That will be reviewed each year to ensure it remains on target - but for a sport that was struggling a few years ago, this represents a remarkable turnaround.

Disability athletics enjoyed the biggest rise within Paralympic sport funding (£4m) - again following a big transformation from Beijing, where the track and field team managed just two golds - both won by David Weir. The London exploits of Weir, Jonnie Peacock and Hannah Cockcroft - to name just three - have ensured a lucrative legacy for their sport.

And while Paralympic swimming was also well rewarded, their Olympic equivalents were dealt a big blow, with almost £4m slashed from their budget for the next four years.

UK Sport's chief executive Liz Nichol insisted this was about Rio potential and not a punishment for failure to deliver on their London medal target. But it didn't feel like that.

The challenge for swimming and all the other sports that have been brutally cut back is to learn from those sports that have excelled. Nichol added that hockey - which received a small increase in UK Sport's announcement - was a good example of a sport that had been on its knees, almost bankrupt, but had subsequently bounced back.

Try telling that to Richard Callicott, a former chief executive of UK Sport who now heads British and English Volleyball. He is furious at the decision to cast smaller sports like his adrift after seven years of pre-London funding. Sport England will plug some of the gaps at the grassroots but Callicott argues the legacy from London will be damaged by discontinuing support at elite level.

Like many of the sports cut yesterday, however, Britain's volleyball teams will struggle even to get to Rio. What's the point in pumping millions of pounds into sports that will not even be at the Games, let alone deliver a medal of any colour?

The other interesting aspect from the announcement was the shifting in the balance of funding between Olympic and Paralympic sports. In the run-up to London, the pie was divided 84% to 16% in favour of the Olympic sports while for Rio it will be an 80-20 split - a tribute to the achievements of Paralympics GB in the summer.

The big question for the government and UK Sport now is whether they can deliver on such bold promises. Here, the experiences of our old rivals Australia might provide important lessons.

Following the Sydney Games of 2000 - where Australia's Olympians and Paralympians also produced unprecedented success - the federal government increased the overall amount of money for elite sport. The move helped Australia win even more golds in the Athens Olympics in 2004.

But after that the funding - and the performances - dropped off, resulting in the team's worst performance for 20 years in London. In a 2009 report, the Australian Olympic and Paralympic Committees said inflation and the cost of sending athletes abroad eroded the real value of the funding package, leading to what was effectively a 30% cut.

Australia won just seven golds in London and finished 10th in the Olympic medal table - down from fourth in 2000. Now another inquest is under way down under in an attempt to work out why Britain's athletes - backed by National Lottery funding - are doing so well.

So if there is any lesson for us from the Australian experience, it is that while you might still enjoy a host-country bounce in the four years after hosting the Games, it's what happens then that provides the real test of a nation's commitment to elite sport.

- Published19 December 2012

- Published18 December 2012

- Published18 December 2012

- Published18 December 2012

- Published17 December 2012

- Published17 December 2012

- Published13 August 2012