Floyd Mayweather: The biggest draw in Las Vegas

- Published

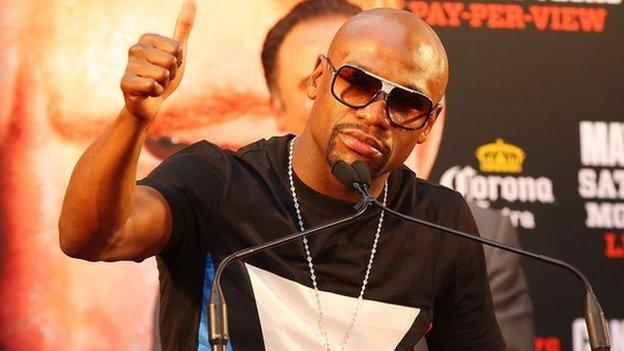

The facade of the MGM Grand hotel here in Vegas is adorned by an image of a grinning Floyd Mayweather.

The poster spans 18 floors of the property which is hosting his showdown against Marcos Maidana, as if to illustrate how big he is in the town they call Lost Wages.

He has had 22 world title fights and four times as many luxury cars. Names like Bentley and Bugatti are so familiar to him he cannot remember where he last parked them. And, in a recent documentary filmed as part of the pre-fight hype, he explained how his wealth has granted him the freedom to spend a million dollars a month for the rest of his life.

The impact made on his adopted home city is such that a prison sentence meted out two and a half years ago was deferred to allow him to fight, his lawyer having argued successfully that a cancellation would cost the local economy $100m. Even in Vegas, it's hard to make that one up.

In December 2011, Mayweather was jailed for 90 days after being convicted on charges of domestic violence and harassment relating to an incident with his ex-girlfriend. He was scheduled to begin his spell behind bars the following month, until his attorney Richard Wright intervened with an appeal "on behalf of the community".

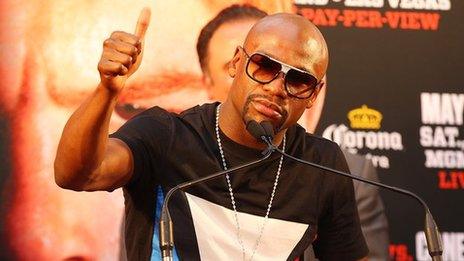

The fighter has revelled in the nickname 'Money Mayweather' and earned an estimated $90m in 2013

Justice of the Peace Melissa Saragosa agreed to delay Mayweather's incarceration, freeing him to face the Puerto Rican Miguel Cotto in May 2012. The boxing authorities offered a helping hand, too. The WBC retained Mayweather as their welterweight champion because the then-president of the organisation, Jose Suleiman, declared that "beating a lady is highly critical but not a sin or major crime".

Mayweather represents a contradiction commonplace among fighters throughout the ages. The chaos and confusion in his life outside the ring is replaced by grace and control inside. His character belongs in boxing - and in Vegas.

Figures released this week show a record number of visitors to this city in a single month (3.7million in March) and of all the attractions up and down the Strip, a Mayweather fight stands at the top of the rankings.

"When Floyd fights here, it's different," Richard Sturm, the president of sports and events at the MGM Grand hotel, told me at the final press conference for the Maidana contest. "There's an electricity you can't describe. Staging an event like this is important not only to our hotel but to the entire city."

"We have a lot of great events, and I mean great events, and they're all very important to us. But a Mayweather fight here is one of a kind. It's the best we have."

His last outing, against Mexican Saul Alvarez in September, was the highest-grossing fight of all time, generating revenue believed to be in the region of $150m. Mayweather signed for a guarantee of $41.5m and Forbes magazine estimated his final take to be double that sum after pay-per-view sales, gate receipts and other incomes were totted up.

The Alvarez fight was the second in a lucrative deal signed by Mayweather with the US cable network Showtime. Comprising six fights spread across 30 months, the contract could eventually boost his earnings by $250m.

Showtime has long been outshone by HBO in the battle of the cable networks here but the gap in subscriber numbers is now closer than ever. Showtime's executive vice-president Steve Espinoza is adamant that Mayweather's influence is substantial: "We went after him, we made a pitch that he liked and there's a theory that a rising tide lifts all boats and I think the spotlight, the visibility he's brought has benefited the whole network.

"I hear once in a while that Mayweather fights are boring. Those people just don't understand boxing. The artistry he displays, the timing, it's like watching a Michael Jordan. He sees things happening in a different speed than virtually every other athlete."

Espinoza gambled but he knew that in Mayweather he was engaging with a man who draws crowds from a range of constituencies. Some want to see him battered, others revel in the flamboyance and the arrogance that have yet to find a boundary. And then there are those who join Espinoza in salivating over a style that is breathtaking and brilliant but also cautious.

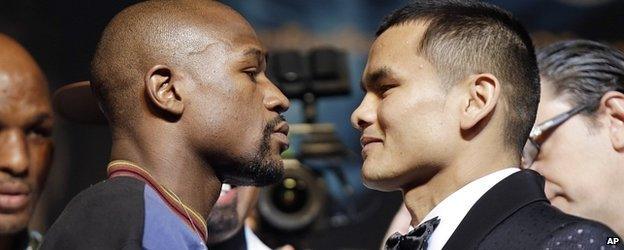

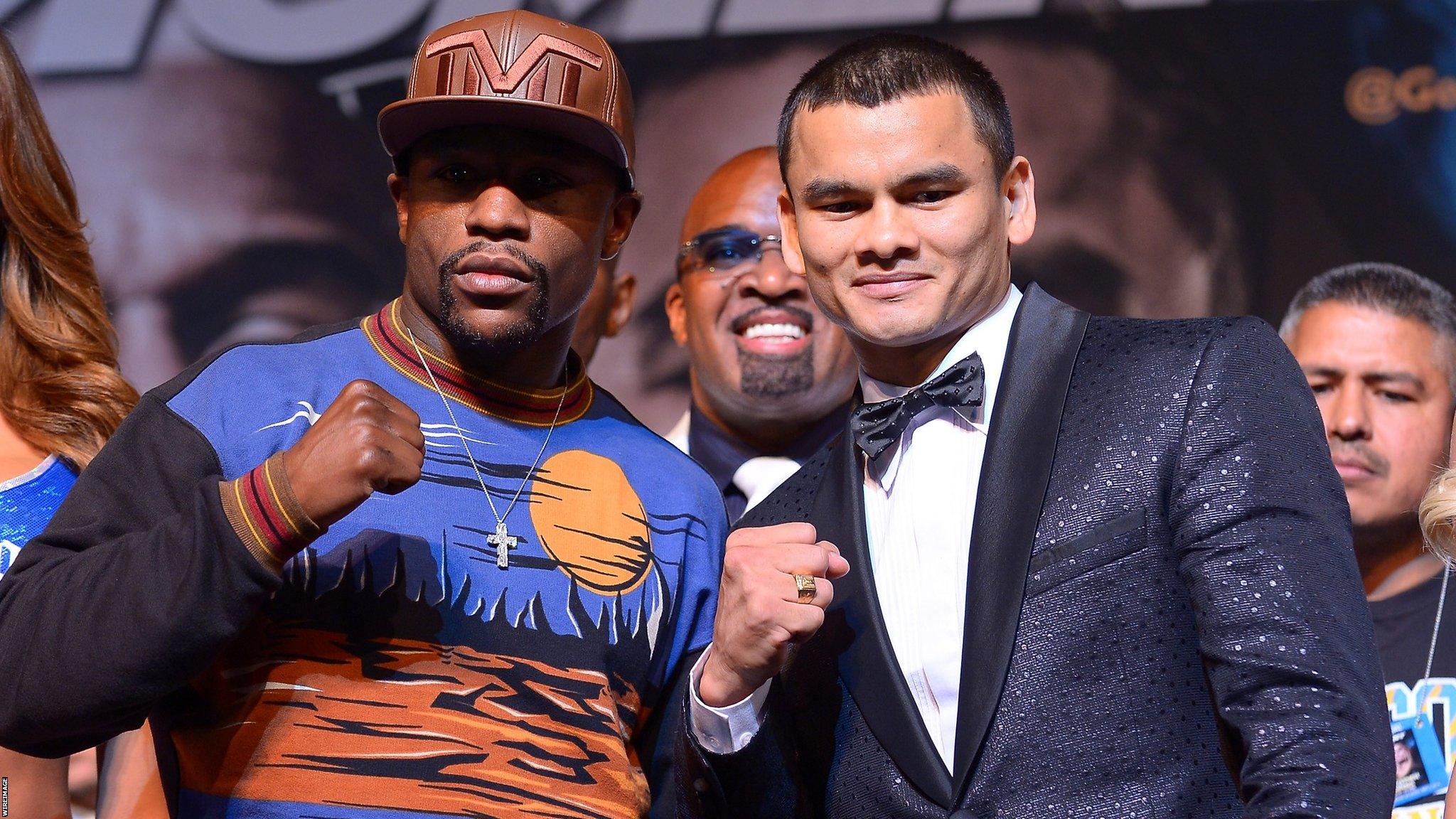

Marcos Maidana lost to Britain's Amir Khan in 2010 and is a massive underdog against Mayweather

Mayweather has only won once inside the distance since he drove Ricky Hatton into a corner-post, external at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in 2007. His defensive genius evokes memories of bygone eras when small-hall patrons would say of seasoned, wily old pros that "you couldn't hit 'em with a handful of rice".

In a study of Mayweather's last 11 world title fights, compiled by the ringside statisticians at Compubox, his opponents landed an average of 18% of the punches they threw. Hatton and Alvarez could testify to the frustration of connecting with only one of every five punches sent on their way. If being hit is the most debilitating and demoralising hardship a fighter must deal with, punching nothing but thin air is a close second.

Alvarez was fancied by a few to prove too strong and robust for Mayweather. In the event, he could have sold his gloves as new after the fight, so seldom did he score. In the latter stages, he appeared unusually hesitant. It seemed as if he couldn't bear to miss yet again so decided to hold back, in a version of what might be termed boxing's yips.

Alvarez returned to action earlier this year with a brutal dismantling of Alfredo Angulo, a performance which underlined the special nature of Mayweather's gift.

Argentina's Maidana is the next to go chasing moonbeams, the latest to attempt to crack what the five-weight world champion is now calling the May-Vinci Code. "You get your biggest purse when you fight me," he boasts.

And when reminded that Bernard Hopkins, at 49 the oldest world title-holder in history, is craftily positioning himself for a pop somewhere down the line, Mayweather spoke for so many in boxing - and in Vegas: "Everybody's trying to hit the jackpot."

- Published2 May 2014

- Published14 April 2014

- Published25 February 2014

- Published22 February 2014

- Published12 September 2013

- Published11 June 2018