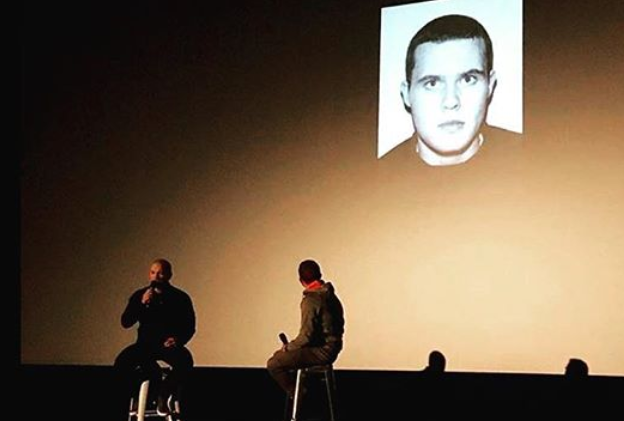

John McAvoy: The ex-armed robber who reformed through sport in high security prison

- Published

McAvoy was sent to prison for a second time following his arrest in 2005, and was released in 2012

At half past eight on a warm September morning in 2005, 22-year-old criminal John McAvoy was ready. He and another man were planning to raid a security van making a delivery of around £100,000 in cash in Eltham, south-east London.

McAvoy did not know there was a surveillance operation watching this man, Kevin Brown. For months police had been observing him, waiting for him to commit an offence.

As Brown approached the van they were targeting, McAvoy, observing from his own vehicle, spotted a police car. What happened next changed his life forever.

"The officers jumped out with all the guns but I managed to drive off," says McAvoy, who knocked over a lamppost as he attempted to escape. "They all jumped back in their cars and chased me and I kept thinking I had to get out as fast as I could.

"I was fully prepared to die trying to get away, because I knew what was coming if they caught me. I was going back to that tiny segregation cell, for a lot longer than the first time."

Now on foot, McAvoy ran into a dead end. With nowhere to go, he was quickly apprehended. It was all over. Brown had been arrested too., external

"I had about 15 guns pointing at me in this little cul-de-sac and I was face down on the floor. I was absolutely deflated," he says.

"They put me in the back of this undercover car and I was pretending I had concussion because I was desperate, thinking they might take me to hospital instead and I could try to escape.

"As I was pretending to drift in and out of consciousness, the same police officer who'd arrested me the first time was calling my name.

"He said to me: 'John, look out of the window.' There were people out on the high street with their shopping bags. 'You will not be seeing this for a long time', he said. I remember thinking I would do absolutely anything to swap places with those people walking down the high street."

The 15 years that followed have led McAvoy along a very different path to the one he had envisaged growing up among hardened members of the criminal underworld.

Over the course of a life sentence partly served in one of Britain's highest-security prisons, it was his best friend's death in a robbery gone wrong that sparked a desire to finally rehabilitate himself.

By the time of his release in 2012, McAvoy had radically turned his life around, and he has since set about encouraging others to follow the same redemptive course he found - in the power of sport.

Now aged 37, McAvoy is a sponsored triathlete who competes in Ironman events. A man who broke three world records and seven British records in indoor rowing, from the confines of the prison gym.

And he has quite a story to tell.

There'd been an earlier occasion in McAvoy's life when he was told to look out the window. That first time was as a young boy, sitting in his step-father Billy Tobin's Porsche. He didn't know what he was supposed to be looking at.

Tobin was a notorious armed robber who engaged McAvoy in a criminal "apprenticeship" from the age of about eight years old.

"All these people out there are sheep," Tobin said, according to McAvoy, who was taught that working and paying taxes would never lead to becoming a millionaire by the age of 21 like Tobin had.

McAvoy's father had died before he was born. His uncle Mickey was involved in the Brinks Mat robbery, external of 1983, when a gang stole gold bullion and uncut diamonds worth £26m from a warehouse near Heathrow Airport, one of the most dramatic heists in British history.

McAvoy's mother, who worked on minimum wage at a local florist in Crystal Palace, was unhappy about her son's exposure to that world, but there wasn't much she could do about it.

"When I was a kid my mum wouldn't even let me have a toy gun in the house to play cowboys and Indians," he says. "She was so anti-gangs, anti-violence. But as I was getting older she could see I was getting pulled further and further into that world.

"She used to say 'you're an accident waiting to happen' and 'if you live your life in the fast lane you will crash and burn'. 'You'll end up how they all end up - living in a cage and going to prison.'"

McAvoy is a regular speaker on prison reform and sport's power to help change lives

The first time McAvoy was sent to jail, it didn't deter him from the life he lived. In fact during his time inside, he was determined not to submit to "the system".

"I had no fear whatsoever," he says. "[Prison] was part of the lifestyle.

"Deep down in your subconscious you have a reality that you are going to get caught. You hear someone's been arrested, you find tracking devices on your car, you know the police are watching you and you're always trying to stay one step ahead of them.

"A lot of the people I was surrounded by as a young boy had been to prison, it was all about not showing weakness and fighting it so that's what I did. I spent a year in a segregation cell, refused to come out, [exercised] in my cell every day, read books, wouldn't interact with the prison regime and was as difficult as I could be."

The second time McAvoy was arrested, his sentencing was much more robust. He was first sent to HMP Belmarsh. High security.

When he went out into the exercise yard for the first time he was met by the London 21/7 bombers, and Abu Hamza, the notorious Islamic extremist. It was then he realised the extent of the trouble he was in.

"It's like your life has been hit by a train," he says.

"The powers that be thought me to be such a high escape risk that they put me with these people that were a threat to national security. I recognised all the faces from the newspapers. Abu Hamza comes up to me, really polite, and says you've just been arrested haven't you, do you need anything? I said no I'm absolutely fine thank you."

Later that day, after returning from a shower, McAvoy entered his cell to find the Qur'an, a packet of Weetabix and some UHT milk on his bed.

McAvoy says: "It was the biggest book I have ever seen in my life! I went back to his cell and said: 'Thank you so much, I'm absolutely fine.' And he said: 'No, no brother, I'm just being polite.' I put it on his bed and went back in to my cell."

Then came the moment that would change his view of the world.

Three years into his sentence, McAvoy was informed of his best friend's death. Aaron Cloud broke his neck and died instantly when he was thrown out of a getaway car after robbing an ATM in the Netherlands. It had a profound impact on McAvoy.

"It was then I realised how precious life is," he says.

"I'd never lost anyone I cared for and suddenly my best friend dies. All the people I'd admired and looked up to since I was a little boy were just old men rotting in prison and they'd done nothing with their lives.

"I got up the next morning and I was completely lost. My reputation, my name, it was meaningless. I looked at myself in that prison cell. I had wasted my life up to that point, down the drain.

"I made the decision: I am not living this life any more."

The prison gym became McAvoy's refuge. It was a way of channelling his energy into something rewarding, an escape from the toxic goings on with other inmates, a chance to do something with his time inside.

McAvoy discovered the indoor rowing machine and found he was allowed more than his allocated time if he was training for one of the many rowing challenges. It gave him focus.

McAvoy (centre) pictured in 2013, a year after his release from prison, at London Rowing Club

At first, he was top of the prison leaderboard. Then, supported by prison guard Darren Davis, he trained for the 24-hour indoor rowing challenge and broke two world records - 100,000m and the furthest distance rowed in 24 hours.

He asked the prison library to order him stacks of books on training and sports nutrition. He wanted to learn about becoming an athlete. In total he became the proud holder of three world records and seven British records in indoor rowing, all achieved in confinement.

"A lot of these characteristics that I had - the will to win and want to be successful - I only used to see in criminals and suddenly there's this other group of people," McAvoy says.

"The mindset was the same but I just had to channel the energy into something positive."

McAvoy's progress was noted, and he was soon put up for parole. But it didn't go smoothly.

"When I went to my first hearing, the judge sat across the table from me and said 'what are you going to do when you get released?'

"I said: 'I'm going to become an athlete'. He was a crown court judge in his 70s. With his glasses on the bridge of his nose he looked up at me with a smile and said: 'In all my years of sitting in hearings for life-sentence prisoners, you are the only one who has sat in front of me and said that.'

"I was absolutely convinced and adamant I was going to do it. But they refused my parole."

However, McAvoy was downgraded to an open prison where he could take qualifications to prepare for an early release.

McAvoy was released from prison in 2012. One of the first things he did - after getting a Nando's and going to see his mum - was to head to London Rowing Club in Putney. He wanted to make it as a professional rower.

Months later when somebody typed his name into a search engine, headlines of his past and his mug shots came up. He decided to reveal his story and was met with understanding, but as it turned out, he was too old to make it in rowing. He turned his attention to endurance sport and triathlon instead, landing sponsorship from Nike and competing in Ironman races.

McAvoy, pictured with Parkrun ambassador Andrew Graham and four-time world Ironman champion Chrissie Wellington

At the time of our conversation, the UK's national lockdown had lifted and McAvoy had ventured to the Alps for a few months to train and work on a project helping young disadvantaged British children experience similar destinations in order to broaden their horizons.

In the UK, he wants to continue pushing for reforms in the prison system that further focus on sport's rehabilitating role. He has his own foundation and is involved in several other charities including Boats not Bars,, external Gloves not Gunz, external and the Twinning Project.

He has campaigned in support of an initiative bringing Parkrun into prisons,, external and backed a 2018 report that recommended lifting a ban on teaching inmates boxing and martial arts. In 2019 he took up an ambassadorial role with the European Commission,, external seeking to encourage more people to exercise.

"I just want to have a positive impact on the world and make up for the all the wrong I've done in the past," McAvoy says.

"Your view and vision of the world is very limited by what you're exposed to as a child. That criminal world had become so normalised to me that I felt everyone else was abnormal.

"Now I look back on it and I can't even believe some of the things we used to do. I have to live with that every day; it's one of the conscious reasons why I do what I do now. Because they're not mistakes, they're decisions. Poor life choices based on what you know.

"Sport changed my life and without it I wouldn't be the man I am today. I am so adamant and so driven that other people get the same opportunity to turn their lives around and find their purpose and direction in life.

"I was as bad as you can get. If I can go through that journey and process of change, it's possible for anyone. I am so determined to help other people get the same chance."