Salif Keita: How Mali's 'Black Panther' became a pioneering icon

- Published

The late Salif Keita of Mali, who died in the capital Bamako on Saturday, was the first African Footballer of the Year

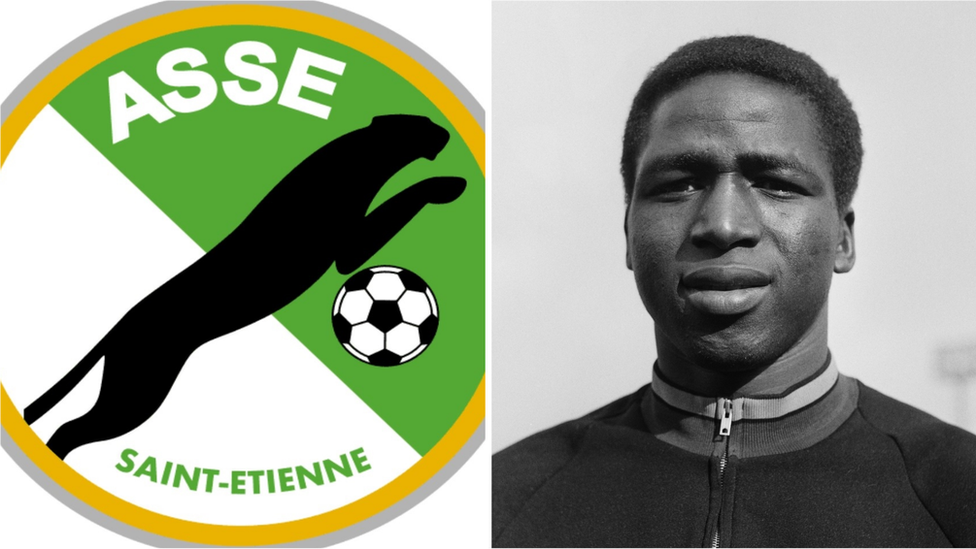

There are very few footballers so well-respected that their club redesigns its logo to incorporate the player's nickname, but that is precisely what happened to Mali's Salif Keita in 1968.

Just a year after joining Saint-Etienne, Keita - who died on Saturday aged 76 - was celebrating not only a French league and cup double but also seeing his nickname, the Black Panther, adorn the club's new logo.

It represented quite a turnaround for a man who famously had to make his way from a Paris airport to Saint-Etienne in a taxi despite having no money after no-one from the club was in the French capital to greet a 20-year-old arriving in Europe for the first time.

From such humble beginnings, which mirrored his own upbringing back home, Keita rose to become not only the first African Footballer of the Year, in 1970, but also a pioneer for the continental talent that has since flooded Europe.

"When I talk about Salif, it's very sad but I'm also very proud because he was an amazing guy," former Liverpool and Juventus midfielder Momo Sissoko, Keita's nephew, told BBC Sport Africa.

"It's a bad moment for everyone, as we lost one of the good guys - someone who achieved a lot for Mali and for all generations in Africa. To lose him is very sad for everyone not just in Mali, but also in Africa."

The death of Africa's first superstar footballer, despite playing in an era when television coverage was minimal in contrast to today, has prompted a range of tributes, with Didier Drogba calling him "one of the greatest legends of African football". , external

Meanwhile, Saint-Etienne deferentially wrote:, external "The Black Panther is gone, taking a piece of our club with him."

In light of his starring role for Les Verts, with whom he won eight trophies in five years, it was a fitting tribute for a forward who lit up French football with his sublime skill and immeasurable talent.

Saint-Etienne changed their banner on X, formerly known as Twitter, after the death of Keita, a club ambassador

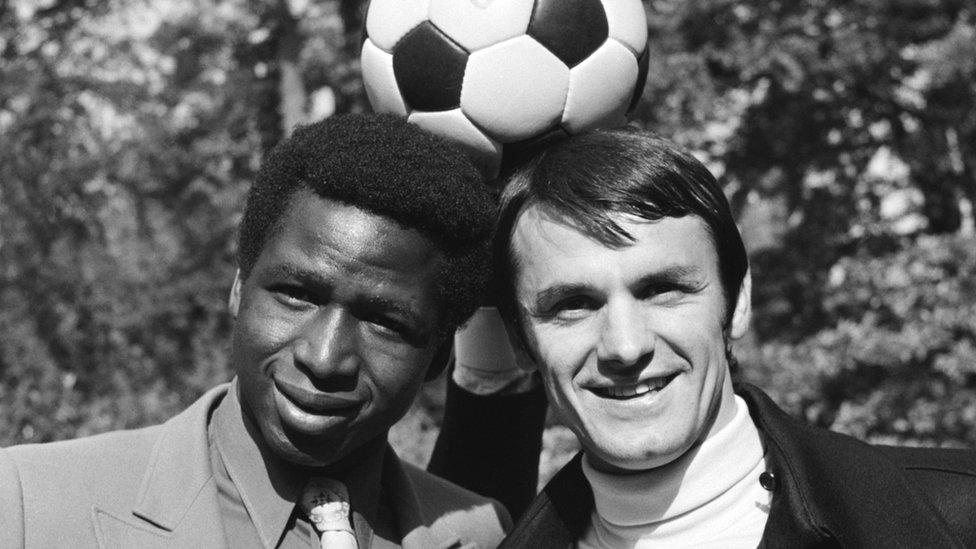

'On a par with Best, Pele and Maradona'

Keita's career began in his home city, where he shone so brightly for Real Bamako and Stade Malien that he caught the eye of a Saint-Etienne supporter in the country.

Les Verts fan Charles Dagher, external was working at the Lebanese embassy in Mali, from where he repeatedly wrote to Saint-Etienne imploring them to not only give Keita a trial, but also keep any such plan secret.

Given that Mali was unlikely to want to lose a man who had taken both his clubs to the final of what is today's African Champions League, Keita was effectively smuggled out of the country - bundled in the boot of a car.

He eventually reached Liberia, where he was mugged of all his possessions, save for the all-important flight ticket sent by Saint-Etienne.

Upon arrival, the letter of introduction sent by the club persuaded a local taxi driver to believe the young African and take him over 500km to Saint-Etienne, where an official paid a fare that would total nearly $1,400 (£1,100) today.

It was arguably the best money the club has ever spent.

In his five years, he won three league titles, two French Cups and his African award - scoring 140 goals in 185 games along the way.

Coupled with his efficiency in front of goal, his silky style of play entranced a nation.

"In the late sixties and early seventies, he was - together with Marseille duo Josip Skoblar and Roger Magnusson - the greatest icon of his age in French football," said long-standing French football journalist Philippe Auclair.

"He was the black guy who every little white boy, including me, pretended to be in the schoolyard - the magical dribbler, the impossibly elegant winger who made and scored wonder goals.

"He was a dream of the player - and that dream was ours. To me, in terms of mystique, he was on a par with (George) Best, Pele and (Diego) Maradona, someone brought from another dimension where football could be poetry.

"I know this sounds over the top but that's how it felt then, and still feels now."

Saint-Etienne's club logo featured a black panther - in honour of Keita - from 1968-78 and from 1988-1993

Despite his aura, a row with Saint-Etienne chairman Roger Rocher prompted Keita to join Marseille in 1972, lasting just a year before the club's attempts to persuade him to obtain French nationality and so abandon Mali - with whom he had lost that year's Africa Cup of Nations final - resulted in a move to Valencia.

His arrival prompted a local paper to scandalously proclaim "Valencia goes after Germans and comes back with a black man", but the first African player in the Spanish club's history put such attitudes to one side to become revered.

"When I talked with Valencia fans, all of them said to me: 'Your uncle was an amazing player and an amazing person'," said Sissoko, who played for the club early in his career.

"He felt very good about his spell at Valencia, often talked about it and had a lot of memories from his time there."

No titles followed in his three seasons there, despite the accolades, and after another three-year spell with Sporting Lisbon, where he won the Portuguese Cup, Keita wound down his career with Boston's New England Tea Men, eventually retiring in 1980.

During his time in the United States, he developed a good friendship with Pele, who had also closed out his career in the North American Soccer League (NASL) two years earlier.

"When two legends are together, they have a lot to talk about," said Sissoko. "He'd talk to me about Pele, saying he was a good guy and the connection was easy as they both came from poor families. They had a very good relationship."

Unforgettable African pioneer

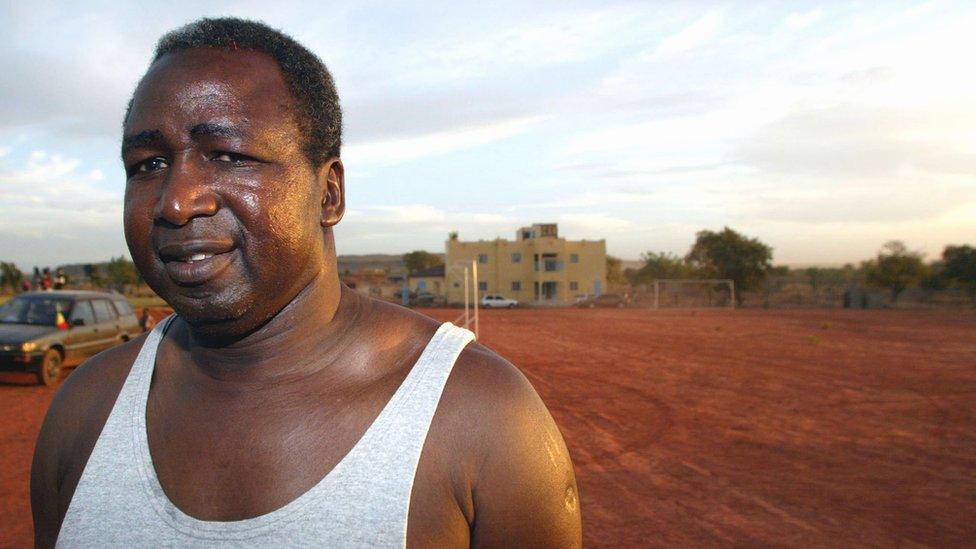

Keita founded Mali's first football academy in his own name in the 1990s, with the academy now a club

Friend of superstars and an icon himself, Keita is remembered as a trailblazing pioneer by many of the African footballers who followed him to Europe - even if the exodus properly began during the 1990s, long after he had retired.

"When we talk about African football history, Keita's name will stand out forever," Nigeria's African champion Emmanuel Amuneke told BBC Sport Africa. "It's very unfortunate we've lost a legend who inspired most of us."

Like Keita, Amuneke would play for Sporting Lisbon, before joining Barcelona and scoring the Olympic gold-winning goal in 1996, a year when Fifa awarded Keita its highest honour - the Order of Merit.

By then, the Malian had founded a football academy which his nephew, Seydou Keita, who would also play for Valencia before winning 14 trophies with Barcelona, passed through - as did former Real Madrid midfielder Mahamadou Diarra.

After a brief spell working for the Mali government, Keita ran his nation's football federation for four years (2005-2009) but was most internationally celebrated when a film loosely based on his life - Le Ballon d'Or,, external in which he appeared - came out in 1994.

The film tells the story of a young boy in West Africa whose footballing dreams soar from several fortunate encounters, one of which comes when his legs are sprinkled with magic - which could of course describe Keita's.

"For a guy from Mali who came from nothing to do what he did, and when he did it, in Europe was amazing," added Sissoko.

"His pioneering role makes me very proud because he was not only my relative but a Malian who showed everyone that when you want something in life, you fight for this - and then you can be a superstar."

Keita won the European Silver Shoe in 1971, with his 42 goals only bettered by the 44 of future Marseille team-mate Josip Skoblar