NFL at Wembley: How a New York office will control Atlanta v Detroit

- Published

The screens in the Game Day Central room can access any of the cameras inside the stadium

Atlanta Falcons v Detroit Lions |

|---|

Venue: Wembley Date: Sunday 26 October Time: 13:30 GMT |

I am standing in a room surrounded by 88 television screens. Each one is showing action from an American football game.

If this were a sports bar, even a fan obsessed with the game would find it too much.

But far from being at a social event, I am inside the nerve centre of the National Football League.

This is where live refereeing decisions are ratified or overturned, game video is captured and stored, data generated and bundled.

If the NFL is a sprawling machine spread across the United States - and, increasingly, Britain too - then this is the cleverest chip in the computer.

The boss here is Dean Blandino, the NFL's vice-president of officiating.

His job, he says, is "making sure the referee doesn't make a mistake".

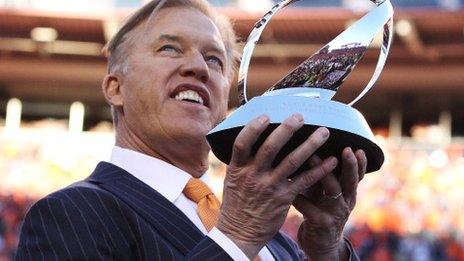

Blandino can communicate with the officials inside the stadium while they deliberate a decision

On Sunday, when the Atlanta Falcons play the Detroit Lions at Wembley, if a contentious officiating decision goes to replay, the final call will be made here, in Game Day Central, on Park Avenue in New York.

The office location is a statement. A visitor to the England and Wales Cricket Board's understated offices inside the ground at Lord's always knows he is firmly inside the cricketing world.

The NFL's Manhattan skyscraper, with its vast atrium and wide corridors, could just as easily host a bank.

Only on closer inspection, when you see the workstations are covered with football memorabilia, do you realise it serves another purpose.

Sport takes on a more naturally corporate sheen in the States, especially American football, the game most deeply entangled, external with big business and the establishment.

At peak moments, 20 assistant referees will pore over the live television streams inside the Game Day Central room.

They use games console-style controllers to dissect footage from each match. Slowing, stopping, rewinding, enlarging, freezing.

During a contentious play, Blandino, external stands alongside the assistant covering that particular match.

The Game Day Central room has 88 screens and 16 replay stations

To be honest, I expected the atmosphere to be more fraught and anxious. In fact, it is urgent but understated and businesslike. Something like air-traffic control, with a splash of Nasa.

Most of the time, information passed to referees on the field of play is routine and the phrase "New York confirms" is often heard, which means everything is fine.

It's when New York does not confirm that the system comes into its own.

The central figure in the Game Day Central room is Blandino, who paces the room judiciously throughout.

"If there's a tight play, I'm already looking at it before a [challenge] flag is thrown," he explains.

The flag indicates that the officials or one of the coaches inside the stadium want a closer look at a particular incident.

Under a canopy on the sidelines of the pitch, the on-field referee views the video evidence while communicating with Blandino and his assistants inside Game Day Central.

Once a decision has been made, the referee announces it to the stadium.

The idea is that technology is expressed through - not in conflict with - the authority of the official on the ground.

Officials inside the stadium view replays on the side of the pitch

This season, Game Day Central has helped to slice six minutes off the average time of an NFL game. Previously, the process of reviewing a decision only began after a challenge had been issued.

The whole system takes its lead from Blandino.

Imagine a wide spectrum of sports officials. At one end is the cynical, ageing ex-player, at the other end is a young, driven and highly ambitious expert. This is the territory occupied by Blandino.

Every decision officials make is assessed for accuracy. They get about 98% right. In other words, there are about three mistakes per game.

At the end of the season, officials are ranked into three tiers. Anyone in the bottom third for two consecutive seasons is at risk of being sacked.

One advantage of new technology, Blandino believes, is that it has helped players "understand how hard it is to officiate".

But he accepts that there must be a balance between a match's organic flow and scientific accuracy of decision-making.

How does Game Day Central work? |

|---|

Each game is watched by a member of the NFL's officiating department inside the Game Day Central room. They will be sat at one of 16 replay stations, each with four screens. The top-left screen shows what the TV audience sees. The top-right screen is the one the referee sees pitchside. The bottom-left screen is a touch screen that can access cameras inside the stadium. The bottom-right screen shows the incident from the best angle possible. The team in the Game Day Central room pick the best shot of the incident for the referee at pitchside to base his decision on. |

Some calls cannot be challenged at all, such as a turnover or a touchdown play.

While watching the New York Jets play the Chicago Bears at the MetLife Stadium, I saw the Jets deprived of a touchdown by a wrong call.

Three mistakes per game doesn't sound like much; but not all mistakes are created equal.

"Those discussion points are part of the beauty of sport," Blandino says. But try telling that to the Jets.

The march of technology is changing the experience of playing and coaching as much as officiating.

The old NFL "playbook" - a massive ring-binder of graduate-level detail about plays that must be learnt by heart - has been replaced by the digital tablet.

The problem? Older players can't remember to charge them.

As with office life in many professions, there is a distinction between tech-savvy Millennials, for whom tablets are the most natural thing in the world, and the more Luddite over-30s.

"My five-year-old son understands it better than I do," said Donald Penn of the Oakland Raiders, about his electronic playbook.

Though every NFL player received a tablet this season, Cleveland Browns coach Mike Pettine issued something else: a pad of paper.

Antonio Cromartie of the Arizona Cardinals consults his tablet during a game against Oakland

Pettine believes that "to write is to learn". And even the cleverest hacker can't decode a notebook hidden in a kitbag.

But the direction of travel is overwhelming: technology is changing every aspect of the game.

Before the Jets match, I spoke to Michelle McKenna-Doyle, the NFL's senior vice-president who is in charge of technology.

She explains that not only do coaches use wifi-reliant headsets, so too does the quarterback.

When you see a quarterback shaking and banging his helmet in quizzical frustration, he is gesturing that the connection is down and is no longer receiving the coach's input.

Sometimes the quarterback is faking it. He wants the coach to think he can't hear instructions so he can ignore him with impunity.

Peyton Manning uses a headset to communicate with the coaching team on the sidelines

"You'll often see Peyton Manning, a real coach-on-the-field type quarterback, gesturing that the technology isn't working, even when it is," McKenna-Doyle explained.

NFL coaches also use tablets to point out opposition patterns or communicate moves to their players.

But there is a catch. They aren't allowed to use video, only still pictures.

This is a rule designed to sustain competitive fairness, in theory preventing rich teams from simply buying in superior technology.

For the same reason, the televisions in the locker rooms aren't allowed to be tuned to the match broadcast.

Whether the NFL's ban on sideline video can hold is uncertain.

The headsets of the Philadelphia Eagles coaching staff prior to the game against the St Louis Rams

The fan experience is accelerating so fast that instant video replay is now available in the stands through official apps.

If everyone else can watch video except the player and coaches, it is logically possible - although highly unlikely - that the head coach could be among the least informed people in the whole stadium.

Eventually and inevitably, video will become a staple of the in-game coaching experience.

Where next? Players already wear Global Positioning System chips inside their shoulder pads.

This allows fans in the stands to monitor the patterns of play and individual acceleration speeds. But the accuracy of the information isn't yet sufficiently convincing for officiating purposes.

"With tracking devices [in the consumer world], it's easy to follow the delivery of a crate of eggs," explained McKenna-Doyle.

"But if you're walking around New York City, GPS gets lost all the time. It jumps. That's what happens when you've got too many moving objects. And that's the problem we're trying to solve for football matches."

A technological challenge? Just what the NFL enjoys best.

Ed Smith is a commentator for BBC Test Match Special. He played three Tests for England and captained Middlesex. He tweets @edsmithwriter

- Published22 October 2014

- Published13 October 2014