Super Bowl 2020: Vince Lombardi, the story behind the name on NFL's biggest prize

- Published

- comments

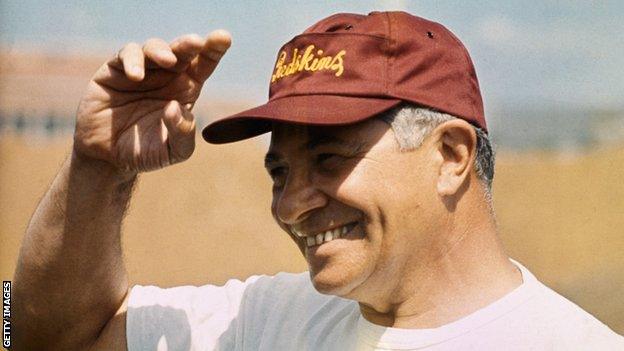

Lombardi's final role was with Washington Redskins, but he made his name at Green Bay Packers

There is a name that resonates with American football fans across generations. When Kansas City Chiefs and San Francisco 49ers meet in the Super Bowl on Sunday, the very prize on offer carries it.

The Vince Lombardi Trophy.

Lombardi was a five-time National Football League-winning coach, an icon of the game who is still celebrated half a century on from his death, as the NFL's 100th season comes to a close.

His legend speaks of a man who inspired players through fear, iron discipline, and confrontational coaching techniques. A leader who took a no-hope Green Bay Packers team and won five titles in seven years between 1961 and 1967.

But beneath the steely exterior of his success are deeper achievements that carry Lombardi's legacy beyond sport, in battling discrimination, championing equality and breaking down racial barriers.

Maybe Lombardi was always destined to teach.

Born in 1913 New York, the son of an Italian meatpacker who studied for the priesthood in his teens, as a young man Lombardi bounced between career paths. Law school and the world of finance didn't suit him. But an offer from an old team-mate to become a high school assistant coach lit an old spark.

Lombardi had played American football during high school, and during studies at Fordham University, before later featuring for minor league teams Wilmington Clippers and Brooklyn Eagles. By 1939 - at the age of 26 - he'd left the game behind, in search of a settled job. Instead, it had found him again.

"Once that opportunity came up, he knew it was what he was meant to do," his son, Vince Lombardi Jr, tells BBC Sport. "He loved to teach and liked coaching."

Lombardi cut short his own honeymoon to make it back in time for training camp at St Cecilia High School. The foundations of the strict, no-nonsense approach that would later become famous were already being laid, with students recalling weeks of "merciless calisthenics" and long sessions late into the evening.

"He was no different at home to how he was anywhere else," remembers Lombardi Jr. "For a coach he had two qualities: he was a perfectionist and had a short temper. For him being my father, those weren't such great qualities."

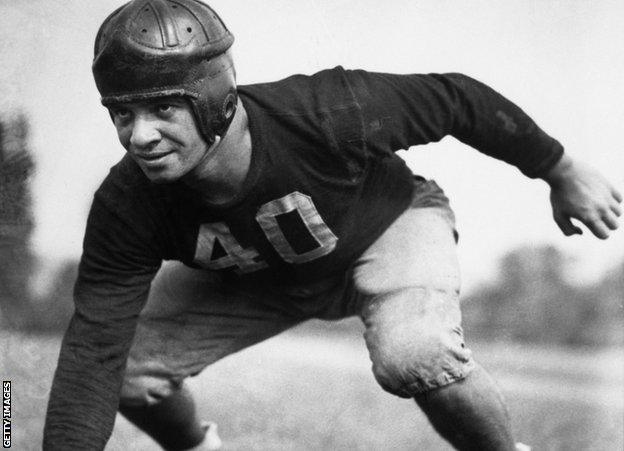

Lombardi, pictured here at Fordham University football practice, in September 1936

Lombardi's knack for getting the best out of his players was obvious. Under his tutelage St Cecilia went 32 games unbeaten and he led the basketball team to the state championship, despite knowing very little about the sport.

A move to Fordham, his old university, followed in 1947, before he took a job as offensive line coach with the US military's side at West Point two years later.

"I remember going to spring practice, standing on the sidelines at games watching him and realising he was the one in command," says Lombardi Jr.

Lombardi's burgeoning reputation earned him a role at the New York Giants in 1954, and then in 1959, at the age of 45, he got his big break. Head coach in the NFL with the Green Bay Packers.

Lombardi's grandparents may have emigrated to the US from Italy, but he was a born-and-bred New Yorker. It was a bold decision to move his family 1,000 miles away to Green Bay, Wisconsin.

This was Lombardi's chance to be in control, to lead his own team. It's just this team were almost broke and coming off the back of the worst season in their history.

Green Bay, perched on the edge of Lake Michigan and home to a Packers side that had not registered a winning season in 12 years, would soon be dubbed 'Titletown' thanks to Lombardi's remarkable success over the next decade.

The rookie boss insisted the Packers would be run on his terms and his impact was instant - Lombardi was named Coach of the Year in his first season, for turning the league's worst side into one that posted a winning record.

"He brought a degree of excellence to the game," Jerry Kramer, an offensive lineman pivotal to Lombardi's side, told an NFL documentary.

"He was a wonderful teacher. He believed teaching was the greatest profession. He said: 'It's not coaching, it's teaching'."

Lombardi famously commented that by chasing perfection "we can catch excellence". In return, the disciplinarian coach demanded complete dedication from his players.

Lombardi, pictured following Green Bay's 1968 Super Bowl title

Defensive tackle Henry Jordan quipped: "Lombardi treat us all the same - like dogs." But he knew which buttons to press to get the best out of each player.

Kramer recalled a story about how he missed a block and Lombardi came running across the field, stopped 10 inches from his face and screamed: "Mister! The concentration period of a college student is five minutes, for high school it's three minutes, kindergarten it's 30 seconds, and you don't have that? So where's that put you?"

Later that day Lombardi, showing the empathy that offset his strict nature, found Kramer in the locker room, ruffled his hair and told him he would be the best guard in football one day.

"From that point on, if he believed in me, I could believe in me," added Kramer, who was later inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

In Lombardi's second season, in 1960, the Packers reached the Championship Game only to fall to an agonising defeat by the Philadelphia Eagles. The boss pledged he would never lose another championship match. And he didn't.

The man dubbed 'The Pope', because he would attend mass every day, led Green Bay to their first title in 17 years in 1961 and another the following season, beating his former employers the New York Giants on both occasions.

During that success Lombardi would be pictured smoking on the touchline, something he deemed a personal weakness. Things changed after he received a letter from a concerned mother in 1963, telling him it set a bad example.

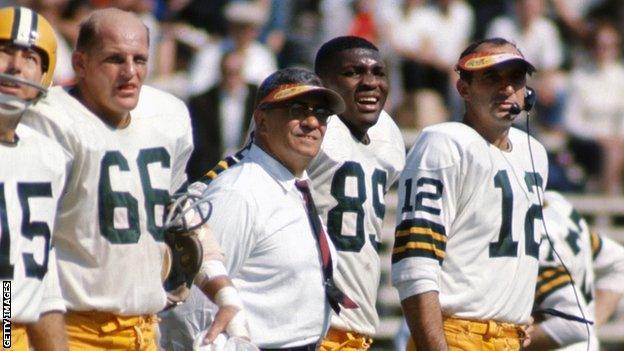

Lombardi looks on from the sidelines during a Green Bay Packers game in 1965

"When he got the letter he quit, just took his pack of cigarettes, crushed them up and threw them in the garbage," says Lombardi Jr.

The assistant coaches at Green Bay, expecting they would take the brunt of their boss going cold turkey, feared him ditching his habit.

"My mother was a prolific smoker, she would light one cigarette as the other goes out," says Lombardi Jr, recognising how difficult that made it for his father to stop.

"She smoked constantly around him so we said he had to quit every day. He was a chain smoker, so to just roll your pack up and throw it away took a lot of discipline."

Lombardi also had to suffer seeing the NFL title celebrated elsewhere for the next two seasons. But he and the Packers responded in 1965 by defeating defending champions the Cleveland Browns, and the following year they beat the Kansas City Chiefs to claim the first ever Super Bowl.

Green Bay then made it an unprecedented three titles in a row when they saw off the Oakland Raiders in 1967. It would prove to be Lombardi's fifth and final NFL crown, as he stepped back to take on general manager duties before leaving for the Washington Redskins in 1969.

But for many, the trophies and titles only tell part of the story. Lombardi was about more than winning.

And so to the other great legacy of Vince Lombardi, whose sporting success came at a time when Jim Crow Laws enforcing racial segregation existed in the southern United States, meaning black players could not stay in the same hotels or drink in the same bars as their white team-mates.

In Green Bay, private housing remained unavailable to a majority of black players, so when Lombardi signed defensive back Emlen Tunnell, who would become the first black player inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame, he put him up at the plush Hotel Northland.

That didn't mean the experienced Tunnell escaped Lombardi's brash and intense manner. He once told a reporter Lombardi was "a real brass, real arrogant", before adding: "But nobody else can cuss Lombardi out to me. In my heart, I know what he is."

Lombardi said he saw athletes as "neither black nor white but Packer green" and demanded everyone be treated equally, refusing to allow any kind of prejudice. He told players if he ever heard discriminatory language they would be "through".

"That goes back to being Italian in New York in the 1920s and '30s," says Lombardi Jr, whose father felt he had been overlooked for jobs earlier in his career because of his Italian heritage, and once got into a fight at university after someone mocked his dark complexion.

Lombardi raises a football in victory, surrounded by reporters covering the first Super Bowl in 1967

"Having experienced something like that, his antenna was up. I don't think it was all that intentional on his part, as much as if you are a good football player and you can contribute to the team that's all that matters."

The head coach increased the number of black players on the Packers roster from just one when he arrived in 1959 to almost a third of the 40-plus squad when he left nearly 10 years later, and as his status grew in Green Bay he began to assert change.

Lombardi told restaurant and bar owners that any place not accepting black players was off limits to the whole Packers squad. He demanded all his players have suitable accommodation and informed teams in the south they would not stay anywhere asking for players to be segregated.

"He slowly integrated us into the city," cornerback Herb Adderley told the Milwaukee Wisconsin Journal Sentinel in 2012. "He said: 'If the black players are going to help this team win, the city needs to understand these players need good places to live.'"

In his book Closing the Gap, former Packers defensive end Willie Davis wrote: "Nobody had more impact in creating diversity in the NFL than coach Lombardi.

"Right from the start he treated us as equals, just players competing for a spot on the team. He chose not to see colour in an era where most chose to look the other way."

Lombardi's quest for equality stretched further than race. His brother Harold was homosexual and he wanted to create an environment of acceptance within the locker room.

During his one season with the Washington Redskins, Lombardi coached running backs Ray McDonald, who was arrested a year earlier for having sex with another man in public, and Dave Kopay, who would later become the first former NFL player to announce he was gay.

"Vince Lombardi had so much humanity. I was just lucky to be around him," Kopay told ESPN in 2013. "Back then gay people were almost thought of as deviant. It really was terrible at the time."

The Vince Lombardi Trophy is up for grabs on Sunday - when Kansas City Chiefs and San Francisco 49ers meet in Miami

In his biography of Lombardi, When Pride Still Mattered, author David Maraniss says the boss told staff working with McDonald that if he heard any "reference to his manhood, you'll be out of here before your ass hits the ground".

The image of a short-tempered, confrontational boss juxtaposed the caring, nurturing mentor beneath and made Lombardi easy to misread. Maraniss says President Richard Nixon once considered him as a potential running mate, only for the Republican to find out Lombardi was a Democrat with close ties to the Kennedy family and someone keen on gun control.

Lombardi's progressive attitudes came in a period when the US was at war in Vietnam and facing violent protests at home. Sadly, his own life would be cut short.

His death, when it came in 1970, was sudden. At the age of 57 he was diagnosed with an aggressive form of colon cancer, and he died 10 weeks later.

According to the Green Bay Press Gazette, President Nixon told a White House dinner party "in a time when the moral fabric of the country seems to be coming apart" Lombardi was "a man who insisted on discipline and strength".

In recognition of his achievements, Lombardi was inducted into the NFL Hall of Fame and the Super Bowl prize was renamed in his honour.

"It seems so accepted," says Lombardi Jr.

"But you feel good about how his name is associated with the trophy. With all the positive things associated with what he did."