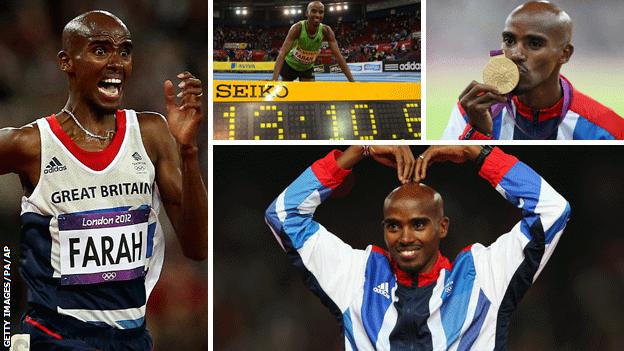

Mo Farah: From Olympic & world champion to marathon novice?

- Published

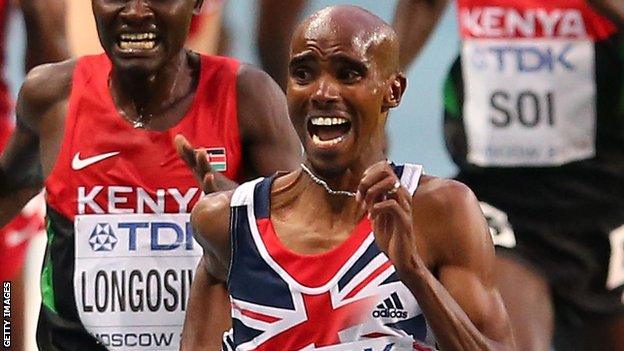

There is a standard protocol now when watching Mo Farah in big races: let him pick his way through the early skirmishes, wait for him to seize the lead just before the bell and then roar him home as the world's best distance runners flap and flutter in his slipstream.

Six times in the last two and a half years Farah has won gold in that fashion, from Korea to Moscow and, most memorably of all, in Stratford's Olympic Stadium. Which will make it all the more unsettling for some to learn that, on his return to the capital for Sunday's London Marathon, he will be running as a novice.

You can forecast a man's 5,000m chances in big championships on his performance in the heats. You can gauge his 10,000m hopes on precedent and form.

The marathon? A long, purgatorial run into virgin territory.

There is no precedent. There is no science to predict what might happen. Farah has run 26.2 miles in training. But he has never covered it at race pace, on asphalt, with rivals pushing and breaking, the course twisting and climbing, emergency sirens wailing from muscle, joint and lung.

And that, for a nation grown accustomed to his peerless track triumphs, may take some getting used to.

"It's inevitable with everything Mo has achieved so far that people are going to expect that he wins it," says Paula Radcliffe, the last Briton to triumph at the London Marathon, external and Farah's friend and advisor since his schooldays in Hounslow.

"He could have a really good run and not win it. It doesn't mean he's run badly, but trying to convey that to other people is difficult because he has done so much. He has achieved so much that people expect every time he steps out he's going to win."

Last weekend the only other man to pull off the world and Olympic distance double-double, Kenenisa Bekele, ran the sixth fastest debut marathon of all time, external in Paris.

That was in a race where he was untroubled by rivals or their tactics. In contrast to that tailor-made itinerary, Farah has chosen to make his own bow on the most public stage of all, against the best field London has ever assembled.

There is reigning London champion Tsegaye Kebede. There is world-record holder Wilson Kipsang, and course record holder Emmanuel Mutai, and Olympic and world champion Stephen Kiprotich. There will be no hiding place, no respite, no easy ride.

Farah has a close affinity with the London Marathon

Farah understands the dimensions of his task. Ever since he moved from student digs in St Mary's in Twickenham to a shared house with Kenya's distance elite back in 2004, spending his evenings watching old VHS cassettes of track greats and marathon classics, he has been the most willing student of his specialised subject.

But even as his body language at his pre-race media interviews appeared bashful - half-sentences, shy grins, lean limbs hidden under baggy grey tracksuit bottoms and an over-sized white T-shirt - his mood was bullish.

"I've gone straight in the deep end, but that's what champions do. London is by far the toughest field anyone has seen. It makes me more of a champion for going out there and going straight in."

Farah's ascent to the elite is intimately entwined with this race. Three times as a teenager he won the mini-marathon, the three-mile race for kids aged from 11-17 that precedes the main event at its Mall finish; after leaving school in 2001, it was a London Marathon scholarship that paid for him to join the newly established endurance performance centre at St Mary's rather than join the army, as he feared he would have to.

In making his debut this year he is being richly rewarded. Yet he is also paying something back, revitalising interest in the elite side of the race for a public that haven't been drawn to it with as much curiosity since Radcliffe's record-breaking deeds a decade ago.

Outside of hardcore athletics fans, most people have grown to think of the London Marathon as friends and fancy dress rather than unmissable sporting drama.

The uncertainty about his performance only multiplies the fascination. How fast can he go? What would constitute success?

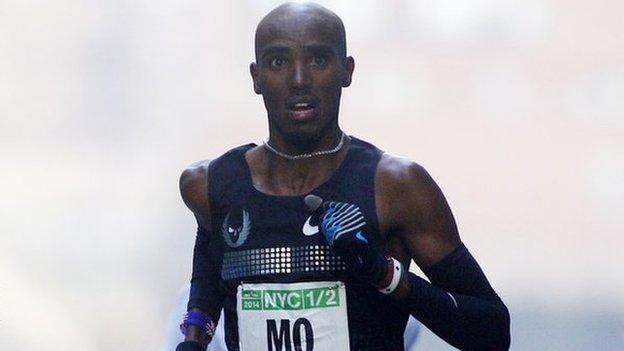

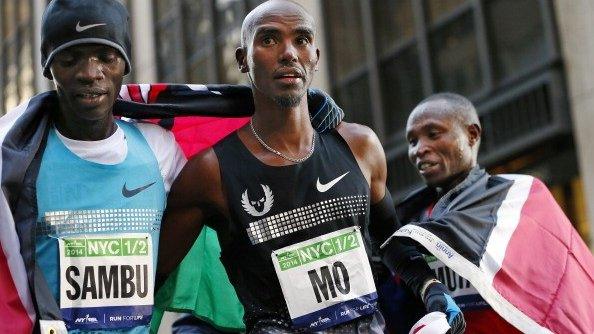

It is notoriously difficult to compare marathons run on different days on different courses, so Bekele's two hours, five minutes and three seconds in Paris may provide only limited guidance; while it is worth noting that the Ethiopian's bests over 5,000m and 10,000m are 16 and 29 seconds faster than Farah's, those PBs were set a long time ago, and the pair were only separated by hundredths of a second over the half-marathon distance of the Great North Run last September.

The man whose distance records Bekele beat, Haile Gebrselassie, ran 2:06:35 on his own London debut in 2002, at the time the fastest debut in history. His great track rival Paul Tergat had clocked 2.08:15 in London the year before.

Neither do those two provide a perfect prediction for Farah this Sunday, but they do offer context: Farah could run brilliantly, beat the great Haile's debut and yet still finish fourth.

What gives those close to him such confidence - there were whispers this week that he is in shape to dip under 2:05 with benevolent weather and a little luck - is that he comes to London off the same formula that has made him the preeminent track runner of his era.

Farah is no longer the callow, talented yet capricious kid who struggled to convert his ability into major medals in the early part of his career. He is in supreme physical shape, the product of his usual winter at altitude in Iten, Kenya, with the solid self-belief of a multiple champion to match.

In coach Alberto Salazar he has a man who knows more about marathon training than anyone else in the world. Just as importantly, Farah, after the unparalleled success the pair have enjoyed together since 2011, takes confidence in everything he advises.

While this is 40,000 steps into the unknown, it is no wild punt. With no World Championships or Olympics this year, Farah can test himself over the ultimate challenge without jeopardising his track status or future goals.

If it works, he may think about a 10,000m/marathon double at the 2016 Olympics in Rio, just as Salazar hinted to me that he would in the aftermath of 2012. If it fails, he can return to the track in time to keep his speed over the shorter stuff.

"With a marathon, it is about racing, to see how you cope with the distance and how your body copes with it," says Radcliffe, who has no fears that Farah's springy track style might not convert to the heavy demands of the road.

"It is refreshing for him to have a new and different challenge. He'll probably still be successful on the track, if not more successful than he has been, with the marathon training behind him, but this gives him a chance to do something a little bit different. Yes, it's challenging, but I think he will be relishing the fact that it is a new stimulus for him."

Gebrselassie will be back on London's streets on Sunday as the elite field's pacemaker, driving them along at close to record pace over the first 30km (18.5 miles). Farah, who will run without a watch ("I'll just go with the feeling"), will want to conserve as much energy as he can in that time, for once letting other athletes dictate, staying safe until at least 18 miles and the multiple assaults that will surely follow.

"In the marathon you really do have to run your own race," says Radcliffe, 11 years on from setting her own unsurpassed world record of 2:15.25 on the same course.

"You have to cover moves and be aware of what others are doing, but you also have to do what's right for your body and do what suits you best. And that's tricky when you haven't run one before."

Farah already has the British records at 1500m, 5,000m and 10,000m. The 29-year-old marathon mark of Steve Jones (2:07:13) is realistically in sight this weekend. Beyond that the boundaries are less certain. London will feel a foreign land.

Mo Farah ready for London Marathon debut

- Published10 April 2014

- Published8 April 2014

- Published8 April 2014

- Published17 March 2014

- Published14 January 2014

- Published6 October 2013

- Published16 March 2014

- Published10 September 2015

- Published8 February 2019