Young, hungry and tough: The rise of British sprinters

- Published

European Championships: Adam Gemili breaks 20 seconds barrier to win gold

British men winning European 100m and 200m gold for the first time since 1998. The first medal by a British woman in a European 200m final in 32 years, the first in a 100m final for 40. An 18-year-old World Junior champion, a 20-year-old running 9.96 seconds.

These are heady times for young British sprinters. Between them they have already won five medals at these European Championships, matching their combined tally at the recent Commonwealths. With the relays here in Zurich still to come,, external they should yet add more.

Why so much success so soon? Can this continental promise translate this to the world stage? And why are so many wise judges more excited about this generation than they have been in many years?

How good are they?

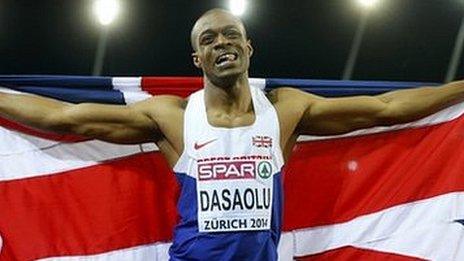

There are the medals - 100m gold for James Dasaolu, 200m gold for Adam Gemili, 200m silver for Jodie Williams - and then there are the statistics around that.

Gemili's time in destroying his French rival Christophe Lemaitre, 19.98 seconds, came on a cold night into a headwind of 1.6 metres per second. On a still day that was theoretically worth 19.90, which would have smashed John Regis's 19-year-old British record.

Williams's 200m was the fastest by a British woman since 1984. Having had no British finalists since 1982, Britain had three women racing for the first time in more than half a century. All were under 21.

Great Britain's sprint stars | |

|---|---|

Adam Gemili, European 200m champion, 20 | Dina Asher-Smith, World Junior 200m champion, 18 |

Chijindu Ujah, European junior champion, 20 | Bianca Williams, Commonwealth 200m bronze medallist, 20 |

James Dasaolu, European 100m champion, 26 | Jodie Williams, former World Junior champion, now European and Commonwealth 200m silver medallist, 20 |

Richard Kilty, World Indoor 60m champion, 24 | Ashleigh Nelson, European 100m bronze medallist, 23 |

Asha Philip, former World Youth 100m champion, 23 | |

Watching it all on television was Chijindu Ujah, whose 9.96 secs earlier this season made him the third fastest Briton of all time, aged just 20.

"What excites me about the girls in particular is that they are showing traits that it took me years to learn," says 1998 European 100m champion Darren Campbell.

"There's a fantastic amount of hunger. They remind me of US collegiate sprinters - sound technique, no big flaws, mentally tough.

"They're fighters. And that is a beautiful skill. When you're tired, tell yourself you're not tired. This is what you will need in your career."

Why so many at the same time?

Britain has always produced talented sprinters, with Olympic 100m champions in 1980 (Allan Wells), 1992 (Linford Christie) and men's relay gold medallists in 2004. Kathy Cook ran times from 100m to 400m in the early 1980s that are still considered a benchmark.

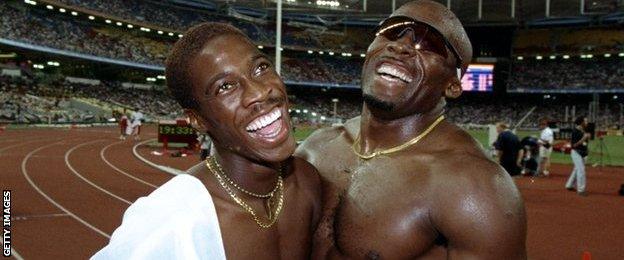

Linford Christie wins the 100m gold medal at the 1992 Olympic Games in Barcelona

Not so often has the pool of talent appeared so deep. A happy accident of talent, or the product of something more systemic?

"I think it's a little bit of both," says Stephen Maguire, British Athletics head of sprints, sprint hurdles and relays.

"We're trying to connect with the young athletes as early as we can. We have all our medical teams under one roof.

"There's a group that's very exciting. It's still pretty raw talent at this stage, but if we can put the right system around them and allow the coaches to give them what they need, the signs are positive."

Christine Bowmaker coaches Jodie Williams and Asha Philip. A former British sprinter herself, she takes a holistic approach with her charges that includes linking up her own training work with that of the athletes' physios and conditioning coaches.

Britons Jodie Williams, Dina Asher-Smith and Bianca Williams all lined up in the 200m final

"The coaching has improved," she says. "You're looking after young people's lives, and you have to appreciate that. You coach the event, but you develop the person.

"I do a lot of reading, listening and watching. There's a sharing of ideas now. Coaches are becoming more professional in everything they do."

"I've seen a different way of thinking over the last five or six years," agrees Campbell, who was coached himself by Christie, and whose World bronze in 2003 remains the last individual medal won by a British sprinter in a global final.

"Some of the work the old-school used to do works to a degree. The new stuff polishes it off.

"Look how polished the techniques of the girls are. The guys are going the same way. We should have a conveyor belt of talent."

A process begun by controversial former UK Athletics performance director Charles van Commenee - hiring overseas coaches to buttress those homegrown ones already in place - continues in moderated form under his successor Neil Black.

While the highly-rated Texan guru Dan Pfaff has returned to the US, he has left a British protégée in Ujah's young coach Jonas Tawiah-Dodoo.

American coach Rana Reider looks after world indoor champion Richard Kilty, European 100m bronze medallist Harry Aikines-Aryeetey and 18-year-old Desiree Henry. At the same Loughborough high-performance centre Britain's Steve Fudge, another who learned much from Pfaff, works with Dasaolu, Gemili and Paralympic champion Jonnie Peacock.

Around them, in the same building, they have biomechanists, physical therapists and strength and conditioning coaches.

"I had to go out and search for answers," says Campbell. "This generation have the answers around them, if they want to utilise the expertise that's there.

"There's been a lot of promise in the past about this person is this and that, when they just have a lot of natural talent. Well, natural talent won't take you all the way.

"What we're seeing now is athletes with natural talent, but the foundations being put in to help them be successful."

The history lesson

Christian Malcolm with John Regis in 1998 after winning Commonwealth silver in Malaysia in 1998

Britain has produced brilliant youngsters throughout the last 15 years. What only a few have done is translate that junior talent to the senior level.

Christian Malcolm, World Junior champion over 100m and 200m in 1998, never broke 10 or 20 seconds as an adult. Neither did Mark Lewis-Francis, World Junior 100m champion two years later, anointed by that year's Olympic champion, Maurice Greene, as the man who would succeed him in Athens four years later.

The best individual performance either man would produce would be a European silver, right at the end of their careers.

At least they competed as seniors. Vernicha James, who beat future Olympic champions Sanya Richards and Allyson Felix in winning World Junior 200m gold in 2002, never made the transition from the juniors.

Neither did Amy Spencer - 100m World Youth silver medallist 2002, winner of the inaugural BBC Young Sports Personality of the Year, or the equally talented Essex sprinter Sarah Wilhelmy, or the 1990 World Junior 200m champion Diane Smith.

Why should it be different this time?

"When you become a senior, it goes from fun to being business," says Campbell. "You need to learn to lose before you know how to win.

"Jodie hadn't lost for 151 races. The expectations and injuries could have broken her, but I think it's made her. Having someone like Christine who has been along some of that journey herself gives you the belief you can come back."

"Jodie has said to me that she doesn't want to the great junior who everyone says didn't make it as a senior," admits Bowmaker. "That was a fear in her.

"But talent doesn't go. It's how you as a coach bring it out of them. Young athletes haven't always been nurtured. I believe in Jodie. I have since she was 12.

"It's why I work with their physios and conditioning coaches. If you have a good support network around an athlete, you can move them forward. And I don't think we had that before."

What this generation might go on to do

Adam Gemili has only been training full time for three years

Next summer brings a world championships in Beijing. Beyond that lies the summer Olympics in Rio, and then a return to London's own Olympic Stadium for the Worlds of 2017. Even by then Gemili and Williams will be just 23, Asher-Smith 21.

"I believe they could compete with the best in the world," says Bowmaker of today's female tyros.

"I'm not just saying that; I can see they have the potential to do it. What they've achieved this year is very good, yet there are areas they have to work on.

"I believe we have a group of young kids that can definitely get medals on the world stage. There are indicators. Look at the structure around them, at their temperament, how they are as people, what the coaches are like."

Jamaica's double Olympic champion Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce has a 100m PB of 10.70 secs and a 200m best of 22.09. New Commonwealth champion Blessing Okagbare has run 10.79 secs and 22.23 secs.

Don't such stellar records and times represent an impossible dream for homegrown sprinters?

"Do I think that Jodie can do what they can do? Yes," says Bowmaker, firmly. "Do I think that Dina and Asha and Bianca and Ashleigh can do that? Yes I do.

"Those people are not unbeatable. The moment we start thinking of them as beatable is the moment we press on and win medals.

"This crop of athletes has belief. People say, ah, they're only winning junior championships. Fine. I say the same to Jodie.

"'Your 200m PB is 22.47 secs. You're going to have to run that to even make a final. To get a medal, you're going to have to run low 22 to 21.9.' That's the reality of what we're dealing with.

European Championships: Jodie Williams second in 200m

"So strength training has to increase. The mental understanding has to increase. They have to understand their body and what it needs.

"There are so many facets to becoming a great athlete, and we're only scratching the surface. But I'm excited about them for that reason - they haven't yet done what they need to do, yet they're doing that.

"I've always believed in British female sprinters, that we could be competitive on a world scale. Nobody believed they could do it. But I'm coaching my athletes to believe you can beat those girls. I don't care who you are."

Campbell, in Glasgow and Zurich in his role as expert summarise for BBC Radio 5 Live, is similarly optimistic.

"You look at the performances of Bianca and Jodie at the Commonwealths, and there's a level of maturity that I've never seen in young sprinters before.

"Dina has that same maturity. That's what makes me think they aren't just flashes in the pan."

How excited should we be?

Dafne Schippers of the Netherlands, just 22 years old, ran the best women's 200m of the year in Zurich as she beat Williams into second place with a stunning time of 22.03.

Six women have run under 11 seconds, 12 men under 10. Even Gemili's brilliant 200m 19.98 is still metres off Jamaican Warren Weir's world lead of 19.82.

There is a significant gap. But these British athletes have time. And while the sport still has issues with doping, there is genuine hope and increasing statistical evidence that the new biological passports are at least making the playing field less uneven.

"We don't want to put too much pressure on these kids, to expect them to just turn round and become Olympic champions," says Stephen Maguire.

"We need to give them and their coaches the space to gradually increase the training load.

"There may be a plateau. That's alright too. Some of the girls may do 11.20 for three years and then they'll drop to 11 zero. You have to meet the athletes where they're at.

"It's important too to put it into perspective. This is a European Championships, not an Olympic Games. It's a little bit of a down year.

"But what has impressed me about the girls and their coaches is that, by 2016, they want to be on par with the Americans and the Jamaicans."

Gemili has only been training full time for three years. Dasaolu, a 9.91 secs man at his best, is only just learning to get his injury-prone body through the three rounds of a major championship. Both Jodie and Bianca Williams, let alone their young team-mate 'Dasher', have physical maturing to do.

Jodie Williams "hasn't arrived yet" - says coach Christine Bowmaker

All that points to the summer of 2014 as the start of something, not the pinnacle.

"I don't think Jodie has put one good race together this season," says Bowmaker. "For me that's exciting, because there are so many areas we have to work on in her development.

"She has strength to improve upon, she has technical aspects to improve. She hasn't arrived yet. She's done well this year, but she has a lot of maturing as an athlete to do.

"I'm under no illusions. To get in the World 200m final next year is going to be hard. We need to run 22.30 to make it. So that's what we're aiming for.

"Medal here and it gives you confidence. It pushes you to a different level. It gives you an air of confidence.

"That's what going to happen with our young sprinters. The Commonwealths and Europeans are an ideal place for development, for getting belief in yourself.

"The British record seems a long way off to some people, but to me it's obtainable. If Kathy Cook could do it, I don't see why out girls can't. They are good enough."

Now comes the hard work

"Greatest isn't given, it's created," says Campbell.

"When Linford said when I was 17 that I was the next Linford, I stopped working so hard because I thought it would just happen. That can't happen now."

Bowmaker is unlikely to let it. "I say to the girls, if you cut out your abs circuits, remember that Shelly-Ann is doing hers.

"When you take two days off over Christmas rather than one, remember Blessing will be training on Christmas Day. That's what you're up against."

- Published15 August 2014

- Published13 August 2014

- Published14 August 2014

- Published16 August 2014

- Published10 September 2015

- Published8 February 2019