Justin Gatlin: Why US sprinter's success is bad for athletics

- Published

- comments

Diamond League: Justin Gatlin wins 100m and 200m double

Twice banned for doping, distrusted by fellow athletes, trained in the past by a notorious doping coach and now by another man once banned for drugs.

Justin Gatlin was supposed to represent the bad old days of athletics. Instead, at an age when most sprinters are slowing down and slacking off, he is closing 2014 as its superstar present: unbeaten all year, owner of six of the seven fastest 100m this season, nominated this month as one of the IAAF's male athletes of the year., external

This has been no quiet drift into sporting old age from the former Olympic and world champion. Aged 32, Gatlin is now running faster than when he was known to be cheating.

This summer he ran the fastest 100m and 200m times by a man in his thirties. Last month in Brussels, he pulled off the fastest ever one-day sprint double, clocking 9.77 seconds for the 100m an hour before running the 200m in 19.71. Two months earlier, in Monaco, he had run 19.68 for the 200m, against a previous legal PB of 20.03.

Shouldn't we be celebrating these great feats of sprinting? Isn't this one of the great comeback stories in sport?

The problem

To subvert that old Lance Armstrong line, extraordinary performances demand extraordinary proof.

Gatlin, banned once as a young man, banned again in 2006 - initially for life, eventually, after negotiations and appeals, for four years, external - is a hard man for many in the sport to trust.

To run 9.77 dirty is one thing. To do so again, supposedly clean, at an age when no other man has got close, is too much for some to believe.

Justin Gatlin factfile | |

|---|---|

Born: 10 February 1982 in Brooklyn, New York | |

Olympic medals: One gold (100m, 2004); Two silvers (4x100m, 2004 and 2012); Two bronzes (200m, 2004 and 100m, 2012) | |

World Championships medals: Two gold (100m and 200m, 2005); Two silvers (100m and 4x100m, 2013) | |

Personal bests: 100m - 9.77 seconds (Brussels, 2014); 200m - 19.68 seconds (Monaco, 2014) |

"It shows one of two things: either he's still taking performance-enhancing drugs to get the best out of him at his advanced age, or the ones he did take are still doing a fantastic job," says Dai Greene, Britain's 2011 400m hurdles world champion., external "Because there is no way he can still be running that well at this late point in his career.

"After having years on the sidelines, being unable to train or compete, it doesn't really add up. 9.77 is an incredibly fast time. You only have to look at his performances. I don't believe in them."

Already Gatlin's nomination for the IAAF's athlete of the year shortlist is causing others to stand up in anger. Germany's Olympic, world and European discus champion Robert Harting, another nominee, is asking for his name to be removed from the list in protest.

"If you did it artificially, you don't know how you did it," says Briton Darren Campbell, a former European 100m champion.

"If you climbed a ladder the first time with a harness pulling you up, how do you do it again without another harness? Would you have the same confidence to attempt that climb without a harness?

"Gatlin must have tremendous mental strength if he believes he can now do it clean."

The science

Athletes have long suspected there might be a long-term effect of doping - something akin to the muscle memory that allows technical motor skills to be retained even after lying dormant for years.

Research from scientists at the University of Oslo from October 2013 appears to give those hunches weighty credence.

"I think it is likely that effects could be lifelong or at least lasting decades in humans," Kristian Gundersen, Professor of Physiology at the University of Oslo, told BBC Sport.

"If you exercise, or take anabolic steroids, you get more nuclei and you get bigger muscles. If you take away the steroids, you lose the muscle mass, but the nuclei remain inside the muscle fibres.

"They are like temporarily closed factories, ready to start producing protein again when you start exercising again."

Gundersen's team studied the effect of steroids on female mice, but he is convinced both the same mechanism is at work in human muscles and other performance-enhancing drugs would have similar long-term benefits.

Famous drug cheats in sport

He said: "I would be very surprised if there were any major differences between humans and mice in this context.

"The fundamental biology of muscle growth is similar in humans and in mice, and in principle any drug that builds muscle mass could trigger this mechanism.

"I was excited by the clarity of the findings. It's very rare, at least in my experience, that the data is so clear cut; there is usually some disturbing factor. But in this case it was extremely clear."

In other words, Gatlin - and others who have returned from shorter bans, like the second fastest 100m man in history, Tyson Gay, former world record holder Asafa Powell and Britain's one-time world 100m bronze medallist Dwain Chambers, external - may still be cashing in those dirty cheques.

The attitude

For all the opprobrium poured on Gay, Powell and Chambers, greater scorn has been reserved for Gatlin.

Part of that is down to the moral distinction some draw between a one-time doper and repeat offender, part down to the American's perceived response to his bans.

Gatlin has never admitted deliberately taking drugs. Where others - notably Chambers - have shown remorse and contrition, Gatlin is as Gatlin was: defiant in celebration, defiant about his past.

Dwain Chambers on doping | |

|---|---|

"It's curiosity, and I was curious at the time. I never realised the magnitude of the mistake or the disruption it would cause. I didn't know. If I could have looked in a crystal ball and seen what happened, I'd never have made that decision. Life is a long motorway. I chose an exit that didn't work for me. If I drove that same road again, I'd read the description on all the signs. I'd choose a different exit. But I went through it." |

"Everyone can make a mistake, so you can forgive something that happens once," says Campbell.

"If you come back and admit what happened, you're trying to stop it happening again. But to pretend nothing happened… I get the redemption thing, but how do you get redemption when you don't admit you did it?

"Working on the law of averages, was he really unlucky enough to twice get caught up in drugs, and be totally unaware? After being caught the first time, wouldn't you be absurdly cautious the next time?"

Gatlin has not tested positive since returning from his last ban. In that time, he has been scrutinised by the US Anti-Doping Agency (Usada). Shouldn't that be enough?

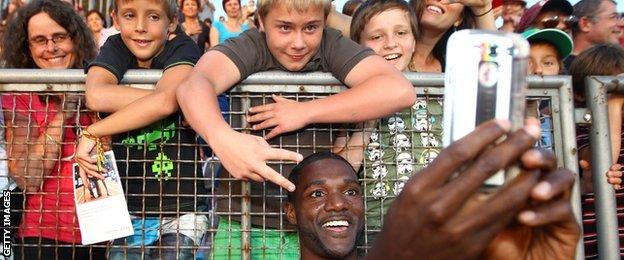

Gatlin takes a 'selfie' with fans after winning this year's Diamond League meeting in Lausanne

"If it's redemption then there should be a humbleness that goes with it, and that's not what we're seeing," says Campbell.

"There's no remorse, there's no 'I'm happy to just be back in the sport'. It's straight back to, 'I'm the man.'

"If I was running, I wouldn't be comfortable congratulating him. I've got no problem being beaten by someone who on that day was naturally better than me.

"But every time you witness a performance, there's a question that pops up in your mind. And that's when the sport has problems, because people are questioning whether what they are seeing is real."

"He doesn't seem to care what anyone thinks," says Greene. "His point of view seems to be, 'I'll become Olympic champion, I'll take shortcuts. I'll be banned, but I'll be making plenty of money when I'm back.'

"Dwain was caught, and when he came back into the team not everyone was happy with it. But he took a back seat, was very private and wasn't in your face about it. And he helped everyone out.

"There is someone who has remorse for what he's done. I don't see that with Gatlin."

The defence

That's the British view, and also largely the Scandinavian one. In the US, Gatlin's return has been treated quite differently. For a seemingly black and white moral issue, there is an awful lot of grey.

Renaldo Nehemiah, a former sprint hurdles star and San Francisco 49ers wide receiver, has worked as Gatlin's agent for more than a decade.

"I say to Justin: 'Listen, some people will never forgive you,'" he told BBC Sport. "Forgiveness isn't a part of their DNA.

Gatlin storms to 200m win in Monaco

"This is a part of your legacy that you will never overcome, because of decisions you made years ago. It may not necessarily be fair, but it's the reality."

In Nehemiah's old league, the NFL, a first offence for steroids carries only a four-game ban. A second will see that stretch to just eight games.

In a country where the most popular sport is so lenient on something considered so grave in Britain, it's perhaps less remarkable to learn that Gatlin is considered a hero rather than an outcast.

"You've got a World Cup player [Uruguay's Luis Suarez] who's biting athletes, not for the first time, and yet he's getting paid handsomely and everybody's OK and it's Kumbaya because he can kick the ball," says Nehemiah.

The Luis Suarez story | |

|---|---|

Barcelona striker Luis Suarez was banned from all football-related activity after biting Italy defender Giorgio Chiellini at the World Cup. After an appeal to the Court of Arbitration for Sport, he was allowed to train and play friendlies. The Uruguayan was previously suspended for biting PSV Eindhoven midfielder Otman Bakkal and Chelsea defender Branislav Ivanovic. |

"Track and field is the only sport in the world that seems to be held to the highest esteem. They're human beings, they're going to make mistakes, and we have to be human and try to allow them to redeem themselves, or not.

"I'm not a fan of people who cheat. I loathe that. But, at the end of the day, we have things in place, punishment and rules, and I accept that.

"I'm not going to spend the rest of my life being mad at an athlete every time I see them or any performance.

"You don't have to support them, but I'm not cut from that kind of cloth. It takes too much negative energy for me to think badly of someone.

"OK, I didn't approve of what they did, but I'm not going to sit up here and not hope that they have come out of this a better person.

"I believe in redemption. I'm not happy about what's taken place. I wasn't happy about it then, but I do believe in redemption, and as long as that's the path that he's on, I will be a party to that."

The attack on the defence

So should we leave Gatlin to it? Nehemiah insists his man, with his tours of schools and colleges for Usada, has more than paid back his moral debts. Doesn't his return - apparently clean, unarguably fast - give athletics a great plot-line?

Greene, a passionate defender of his sport's many clean athletes, does not think so.

"Cheats steal headlines from other people, they steal finance from other people, they steal medals from other people.

"British 100m sprinter James Dasaolu is running incredibly well. He'd be winning Diamond Leagues at his best. But he can't get anywhere near Gatlin. And it's people like James who could be missing out.

"I'd be distraught if I were second or third in the world and there was a guy a second in front of me who was found to be cheating. It would be very difficult for me to take.

Gatlin finished second to Usain Bolt in the 2013 World Championships - could he beat the Jamaican at next year's Worlds in Beijing? And win gold at the 2016 Olympics in Rio?

"It's their win he's taking, their coverage. You have a short career in athletics, and if that success is being taken away by someone who has cheated, that's very frustrating."

Nehemiah points out that Carl Lewis and Michael Johnson also ran fast times in their 30s. He flags up Gatlin's fine record in college. The message is straightforward: why shouldn't you believe?

"Justin Gatlin would've run this time, and faster, had his over-zealous coach Trevor Graham, external not tried to get him there sooner than he would've naturally gotten there.

"What Justin is doing right now, I'm not surprised. His body is rested for four years, so he wasn't racing. And he was the talent that I always knew he was.

"So between the rest, and the talent that he always had, and the determination to prove everyone wrong, that he was always this good, you have it.

"I even told him when he was running this year: 'I get mad every time I think of the four years, because you would've been doing this and better. And what the four years did was took away some of the things that you could've done even more remarkable. But now, you're fighting.'

"There are going to be suspicions. That's the era that we live in unfortunately. When I was an athlete, there was only certain Eastern Bloc countries that there were suspicions about, and the sport was a beautiful thing to watch and we enjoyed it.

"Today, it's unfortunate we can't even watch a meet without innuendo of drugs. And I guess that's the climate we live in. No matter how much they test, there's no-one that's going to believe any athlete is capable of performing a certain feat."

The clouded future

One of the reasons for that suspension of belief is, of course, the repeated transgressions of star names like Gatlin.

Even now, in his supposed fresh start, he has not done everything in his power to keep his name clean.

Formerly coached by Trevor Graham, now banned for life after eight of his athletes - including Olympic sprint champions Jones and world 100m record holder Tim Montgomery, external - were banned for doping, he now works under Dennis Mitchell, himself banned for two years as an athlete after testing positive for excessive levels of testosterone., external

For a man so keen to protest his innocence, it appears at best a misguided decision, at worst a blatant signal of contempt for those critics.

"You have to understand we only have so many coaches in America that have knowledge," insists Nehemiah.

"I would venture to say there aren't too many coaches around in the world that haven't worked with an athlete or someone at some point that's done something they shouldn't have done.

"It wasn't as if Dennis was a perennial abuser of drugs. He had an incident, he paid the price for it, it was years ago and he hasn't had an incident since his return in a coaching capacity, since with any athlete.

"And he lives in Orlando, Justin lives in Orlando and it just makes sense from a convenience stand point. Justin's a Florida boy, you're looking at Florida coaches, we don't have that many, and that's who we chose."

Neither are those who run athletics entirely without blame.

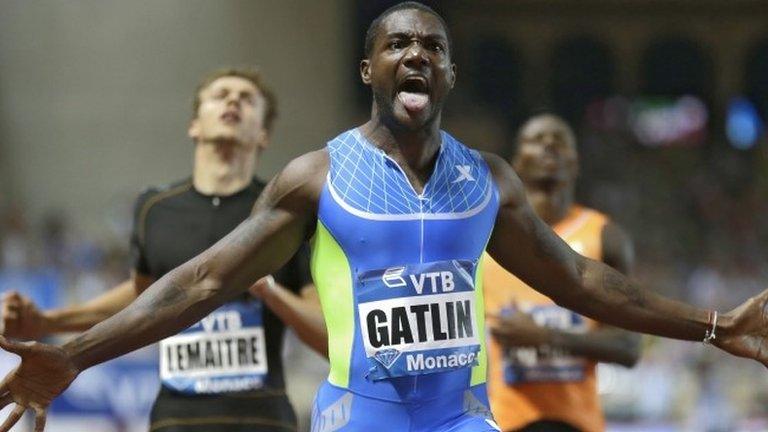

Justin Gatlin, Michael Rodgers and Tyson Gay, who have all failed drugs tests, compete at this year's Diamond League meeting in Lausanne

Since French 1500m runner Hind Dehiba won a court case, external against the organisers of the Lausanne Grand Prix meet, other big events have set aside their previous collective decision not to invite and pay convicted drugs cheats.

But there has been no counter-challenge, and there has been little resistance to promoting former dopers like Gatlin and Gay as the poster-boys and heroes.

Then there is anti-doping agencies' increasing preference for cutting bans in exchange for information.

Gay had his original two-year ban cut to just one. In the long term it may work - it was how Usada finally snared Armstrong - but it also raises serious moral questions: can you really be said to be helping the authorities when you were deliberately defrauding them until caught?

"How do you want your sport to be perceived?" says Campbell. "Do you care how medals are won?

"For me you should always care. Because people need to believe what they're watching.

"If you're not bothered about what athletes do to achieve success, you've got a problem. You'll keep the hardcore fans. But you'll lose the rest."

- Published7 October 2014

- Published5 September 2014

- Published5 September 2014

- Published18 July 2014

- Published4 June 2014

- Published6 June 2013