Paula Radcliffe: Pregnancy, motherhood and marathons

- Published

Marathon world record holder Paula Radcliffe became pregnant when she was a successful athlete. As part of Women's Sport Week,, external the mother-of-two talks about her decision to put her career on hold and explains how she went on to juggle motherhood with a successful running career.

Most women are aware of their biological clock and know the decision to have children or not is a choice they will have to make. There's no set formula, everyone has to make the decision that's right for them.

Becoming a mother was something I had always envisaged doing. Even before I had aspirations of being an athlete, I imagined having children and it wasn't something I wanted to sacrifice. But I didn't foresee a time when I wouldn't be running so I knew I'd have to work it in somehow.

Read more: Women's Sport Week |

|---|

What I didn't want to do was get to the end of my career and find out I couldn't have children because that would have been heartbreaking so it was a case of trying to plan it, but becoming pregnant is not something you can always plan. As someone once told me, you'll never find the ideal time but, whenever it happens, it'll end up being the perfect time.

My husband Gary and I were lucky. We'd discussed it and set a cut-off point: 'If I'm not pregnant by a certain time before the Beijing Olympics we'll stop trying, get through Beijing and try again afterwards.' As it happened, I became pregnant quite easily.

Gary is not only my husband but my coach and manager, yet our conversations about pregnancy and parenthood weren't the discussions of an athlete and her coach or manager, but those of a wife and husband.

I hadn't been secretive about wanting children, so close friends and family guessed when we told them we had big news and I didn't ask anyone for advice about becoming pregnant, but once I was pregnant I did seek out former athletes who had experienced it.

Radcliffe's husband, Gary, and children, Isla and Raphael, were waiting for her on the finishing line when she completed this year's London Marathon

I was fortunate I had role models, people like Liz McColgan who won a world championship in 1991, the year after her first child was born, and Irish runner Sonia O'Sullivan,, external who won silver at the 2000 Olympics the year after giving birth.

I didn't see a reason why I wouldn't be able to return to the same level I was at before getting pregnant, I just assumed that I would, but I do remember emailing Liz and speaking to Ingrid Kristiansen,, external the Norwegian former world 10,000m champion, about training during pregnancy.

Liz just told me to drop the intensity a little and to listen to my body more.

Michael Dooley, fellow of the Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, also gave me a lot of advice. His guidance was of a more technical nature, informing me about things like staying hydrated, not letting my heart rate go too high, to eat soon before and after training. I spoke to him after childbirth as well.

My priorities changed the minute I knew I was pregnant and everything I did centred around the baby. I lost that competitive instinct. It wasn't about running certain times in training anymore, it was about making sure running was a comfortable experience for the baby.

Michael reassured me exercising while pregnant was actually good for the baby, that the training would make the baby stronger. That was nice because you do get silly comments from people.

He said the baby was going to be healthier if I exercised while pregnant, rather than sit on the couch, because I'd be fitter for the labour and would recover better, while the baby would have been exposed to small amounts of adrenaline, allowing it to cope better with the stress of childbirth.

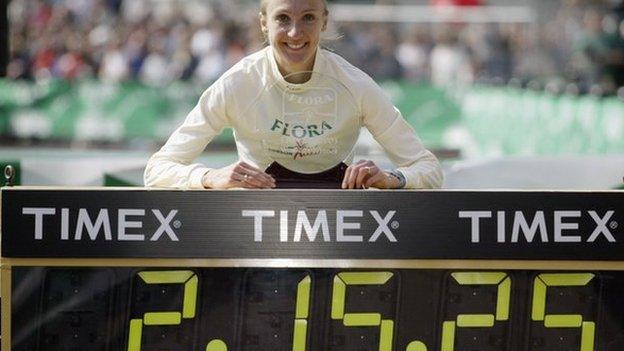

The world record Radcliffe set 12 years ago is still three minutes quicker than anyone else in history has run

I had a good pregnancy with Isla, who is now eight years old. I was able to do most things. It was quite a humbling experience at first because, as an athlete, you're used to being in control of your body but in the first few months I was tired and had no energy and it was all because of this tiny foetus.

To think such a small thing could make a body that usually responded and coped with many miles of training want to sleep all afternoon was humbling.

I was back running about 12 days after giving birth to Isla, which was too soon. I was really excited and probably built the miles up too quickly, which is how I ended up with a stress fracture in my sacrum (a bone at the base of the spine). I hadn't recovered from the trauma of the birth - an agonising 27 hours in labour - so there was a lot of bruising and I ended up not being able to run for three months afterwards, although 10 months after giving birth I did win the New York Marathon.

After my son Raphael was born it was about three-and-a-half weeks until I tried running again. Raphael's birth was a traumatic one, too.

Famous sporting mums | |

|---|---|

Paula Radcliffe won the 2007 New York marathon 10 months after giving birth to daughter Isla | Kim Clijsters triumphed at tennis's US Open in 2009 to become only the third mother to win a Grand Slam |

Liz McColgan returned to athletics after giving birth to her first child, Eilish, and won 10,000m gold at the 1991 World Championships | Fanny Blankers-Koen, then a 30-year-old mother of two, won gold in the 100m, 200m, 4x100m relay and 80m hurdles at the 1948 Olympics in London |

Pregnancy is difficult for an athlete because in most careers you take a couple of months off work towards the end of the pregnancy, but if you're an athlete you're unable to do your job for pretty much the entire nine months. Plus, there's the recovery period after labour.

But once you're ready to come back, being an athlete makes things almost easier because it's a profession which allows you to combine training with parenthood. When I was an athlete I could spend lots of time with the kids and work training around them, and when they were babies our rest patterns were the same. I'd go training in the morning, play a little with them and then we'd nap in the afternoon.

It worked because I was so much happier having the kids in my life and the children gave a lot in return. They gave me energy - I was happier so I trained harder. And it was the same for Gary as well, so we became a stronger team.

I needed to be more organised and had to lean a bit more on the extended family, getting grannies to come along to help in training camps, and without their support it probably wouldn't have been so easy but I was lucky.

Life became harder once Isla started school because before then we were able to travel as a family. But once she was at school I had to go away to training camps on my own, which was hard, though probably harder on me than them because they were being looked after properly.

The longest I was at a camp was the five weeks I spent in Kenya training for London 2012. I missed them and felt guilty they didn't have their mum around, but it was a one-off and I was there working, providing to support them.

I'd Skype them every day. The rest of the team used to tease me because when I wasn't training I'd be permanently attached to my iPad, just in case they wanted to reach me any time. Skype made life easier because Isla could show me what she'd done at school and I could read bedtime stories to them both.

I still travel quite a bit with work these days, for ambassadorial roles, talks and commentating for the BBC. But I'm away for shorter periods, a couple of days rather than weeks - unless it's during a major championships.

It's difficult missing out on school plays or not being able to be there for a gymnastics competition which Isla really wants me to be at. It's hard, but I'm sure it's something every parent experiences.

- Published7 June 2015

- Published4 June 2015

- Published24 April 2015

- Published5 June 2015

- Published10 September 2015

- Published8 February 2019