Questions mount over Alberto Salazar's links to Mary Slaney

- Published

Mary Slaney (right) failed to finish the 3,000m final at the 1984 Olympics after colliding with Britain's Zola Budd (left)

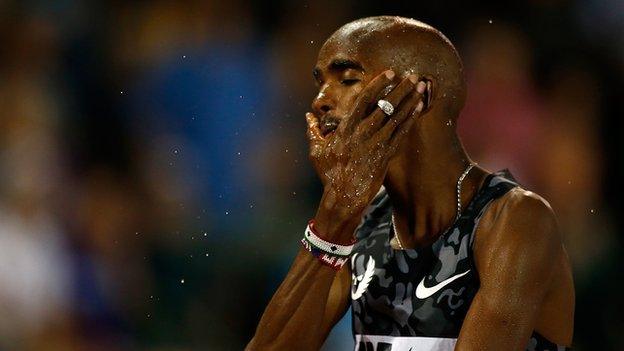

Fresh doubt has been cast on assurances Mo Farah says he was given by Alberto Salazar about his links to Mary Slaney, who failed a drugs test in 1996.

More evidence has emerged that Salazar was coaching the American runner when she tested positive for elevated levels of testosterone.

After a long appeal, middle-distance runner Slaney was eventually banned.

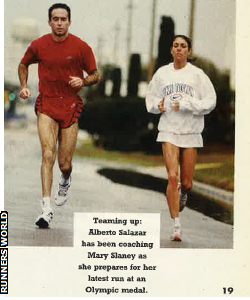

Salazar was pictured with Slaney in Runners World in 1996 (interview below)

According to Farah, Salazar has assured him he was not coaching her when she failed the test at the Olympic trials.

"That's the question I asked before [joining Salazar's training camp in 2011] and Alberto said he wasn't coaching her at the time," said Farah.

But contemporary coverage suggests otherwise.

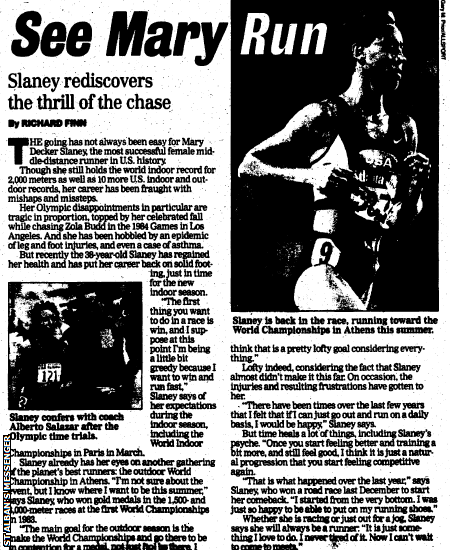

The BBC has discovered a joint interview with Salazar and Slaney, who used her maiden name Decker for much of her running career, in the June 1996 edition of Runner's World.

The Cuban-born Salazar, 56, is described as "her coach" and they are pictured running together. The article quotes Salazar on Slaney's chances at the trials and he details her training regime.

The article clearly places Slaney, best remembered in the UK for tangling with Zola Budd, external in the final of the 3,000m at the 1984 Olympics, and Salazar together in the run-up to the US trials.

There is another article with a picture of the pair in the St Alban's Messenger, a newspaper from Vermont, dated 19 February 1997.

Alberto Salazar coached Mo Farah (right) and Galen Rupp (left) to gold and silver respectively in the 10,000m final at the 2012 Olympics

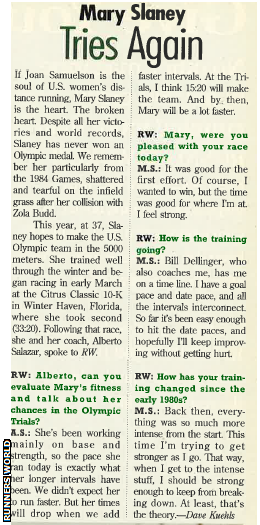

"Slaney confers with coach Alberto Salazar after the Olympic time trials," is the caption below the picture.

Coverage of the two can be found in an article in a Massachusetts newspaper, too - the Worcester Telegraph and Gazette - written on 19 June 1996, two days after the trials.

It says:

"Mary is like a race horse," said coach Alberto Salazar, who has tried to rein in Slaney's obsession by limiting her training.

"She's got a lot of heart and she'll run herself into the ground. She is so biomechanically gifted. Maybe 99% of her body is ready to do something and 1% - one little tendon - isn't ready."

The St Alban's Messenger newspaper described Salazar as Slaney's coach in February 1997

Coverage of their athlete-coach partnership can also be found in national titles.

A 1994 profile, external of the athlete in People magazine said Slaney "turned to her friend Alberto Salazar… to help devise an injury-free programme for her", while a New York Times article, external from May 1996 refers to Salazar as "her coach of two years".

These reports - and numerous others - chime with the memories of two men close to the situation in the summer of 1996.

John Cook, a former colleague of Salazar's, told the BBC that the Cuban-born coach was part of Slaney's camp.

"[Salazar] told me he was coaching her, so I guess now he's removing himself from that," said the American, who helped Salazar set up his Nike Oregon Project running stable.

"But he was certainly her coach. Mary had several coaches at [her US running team] Athletics West."

When asked to clarify that Salazar was one of those coaches, Cook said: "Absolutely, he takes credit for that."

Cook's recollection corroborates what a senior American athletics reporter told the BBC this week - Salazar "was absolutely coaching Slaney" when she failed her test.

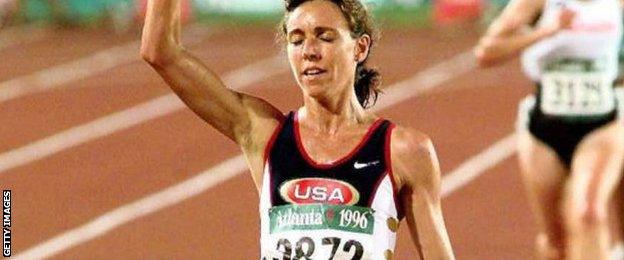

Slaney was eliminated in the 5,000m heats at Atlanta 1996, and so went the American middle-distance great's last chance to win an Olympic medal

The reporter, who does not wish to be named, said he spoke to both of them at the news conference in Atlanta after the then 37-year-old Slaney had confirmed her qualification for the 1996 Olympics in the 5,000m.

According to further press clippings, their relationship continued after Slaney's positive test.

A report from 1997, in The Oregonian, quotes Salazar - "Slaney's coach and confidant" - as saying she would return to the sport, and the pair have always denied that Slaney took testosterone, blaming the positive test on birth control pills.

A 1998 article in a South Carolina newspaper, The Item, reported that Salazar had found the two Duke University law professors she used for her unsuccessful appeal against a two-year drugs ban.

The link between them is even referred to in Salazar's 2013 autobiography,, external in which he wrote: "I also coached my good friend Mary Slaney, the American middle-distance legend, at the end of her career."

On Friday, Slaney said she disputed the test and the finding, with her lawyers arguing her case should never have been brought or prosecuted. But she did not clarify her relationship with Salazar.

The BBC has asked Salazar to clarify his relationship with Slaney in 1996, but he has yet to respond.

After a long appeal process over her ban, Slaney (right) was eventually stripped of a silver medal she won at the 1997 World Indoor Championships in Paris

Farah's comment about the assurance Salazar had given him on his links to Slaney came during an emotional news conference dominated by questions about the wider allegations against the coach, specifically that he doped Farah's training partner Galen Rupp in 2002.

There is no suggestion of any wrongdoing on Farah's part, while both Rupp and Salazar strongly deny the allegations.

The Slaney story predates these claims but now has a fresh significance because of what Salazar told him about his ties to the runner.

It also raises questions about the "due diligence" UK Athletics claims it did on Salazar before letting Farah join the Oregon Project and again when it gave Salazar a consultancy role, external with UK Athletics in 2013.

UKA's performance director Neil Black was seated alongside Farah, a double Olympic and three-time world champion, on Saturday and assured journalists that the governing body had quizzed Salazar about Slaney.

Ian Stewart, the national governing body's former head of endurance, told the Daily Mail, external on Thursday that he "knows for a fact" that Salazar "never coached" Slaney.

When asked for a response to the evidence outlined above, UKA replied: "Whilst the internal review [into the allegations against Salazar] is taking place it is inappropriate for us to comment on individual matters raised by reports."

Salazar has not spoken publicly since the BBC and ProPublica revealed the results of their investigation.

But he has issued a statement that said he intended to "document and present facts as quickly as I can so that Galen and Mo can focus on what they love doing and have worked so hard to achieve".

Farah pulled out of the 1,500m at the Birmingham Grand Prix on Sunday, saying he was not in the right mental state to compete and would be returning to the US to seek answers from Salazar.

Farah, who has repeatedly said he has never been asked by Salazar to do anything that would fall foul of World Anti-Doping Agency rules or witnessed any such behaviour, said he would quit the Nike Oregon Project if "clear evidence" of cheating emerged.

The text of Slaney and Salazar's joint interview with Runners World in 1996

- Published11 June 2015

- Published8 June 2015

- Attribution

- Published3 June 2015

- Published10 September 2015

- Published8 February 2019