Mo Farah's World Championship wins are anything but routine

- Published

- comments

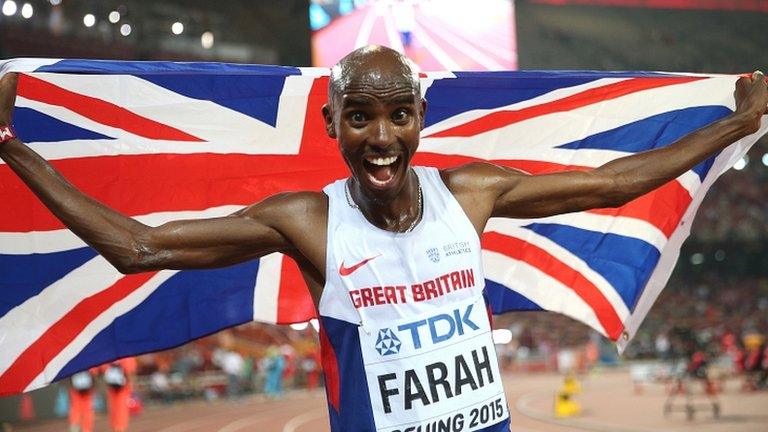

Farah completes historic double

World Athletics Championships |

|---|

Venue: Beijing National Stadium, China Dates: 22-30 August |

Coverage: Live on BBC TV, Red Button, Radio 5 live, online, mobiles, tablets and app. Click here for full details. |

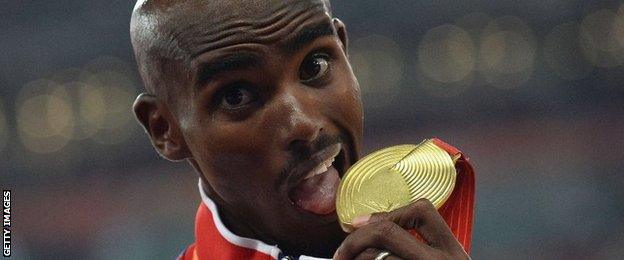

Should you for some reason be in danger of taking Mo Farah's achievements for granted, after his fifth World Championships distance gold, his sixth straight season dominating each year's biggest championship and his seventh global title, there are a few things you might wish to consider.

Here's an example of a training session he ran a few weeks ago.

A mile knocked out in three minutes 55 seconds. Two-lap jog as recovery. Then a 1,200m run in 2:57. Same recovery. Then 1,000m in 2:27, two laps recovery; 800m in 1:57, two laps recovery; 600m in 80 seconds, two laps; 400m in 50.4, two laps; 200m in 25 seconds.

All done at 1,300m altitude.

Attempt any element of that on its own. Try one 400m lap of your local athletics track in 58 seconds, the time he was averaging across that session.

When you have cleaned up the mess, consider that this example is notable only for being not that notable. This is a physical nightmare that Farah lives most days.

Jump forward to the eve of a big championships. Many athletes turn up in peak condition for one. Lots turn up in peak condition for two. Not so many do so for three, far fewer for four.

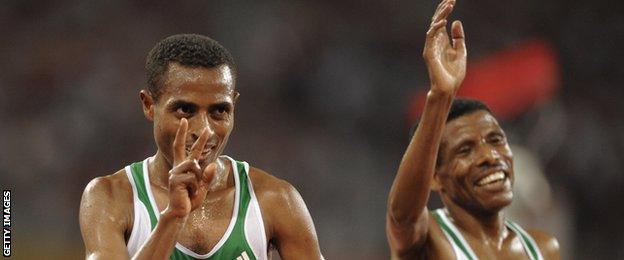

Farah has never run the times set by Bekele (left) and Gebrselassie at their best but his major championships record surpasses both the Ethiopian distance greats

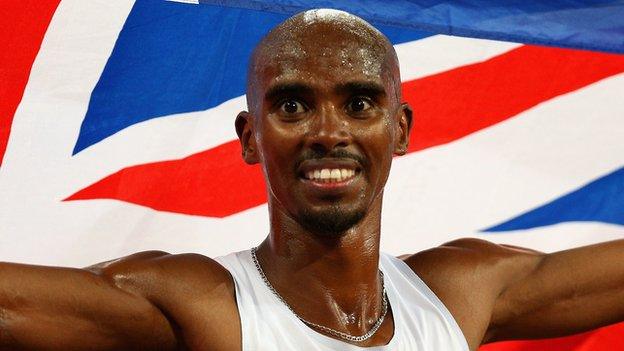

Farah has now arrived in perfect physical shape for the past six summers: Europeans 2010, Worlds 2011, Olympics 2012, Worlds 2013, Europeans 2014, Worlds 2015. At each of those he has also carried complete confidence that he can beat everything that anyone else can throw at him, and been proved right.

What of the contest itself? When Tiger Woods - rightly considered extraordinary for winning 14 of his first 46 majors - settles over his ball on tee or green, he is executing a closed skill. The only one who can affect the club or ball is him. There will be immense pressure, but there will also be silence.

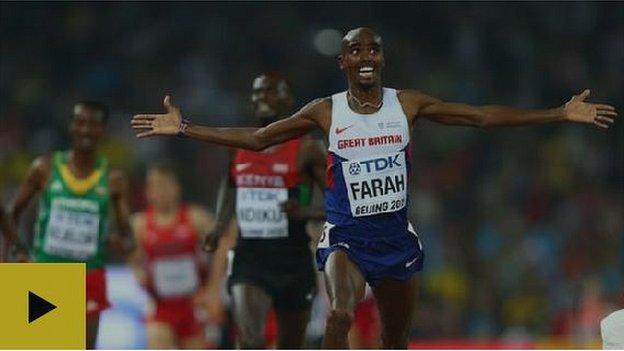

Mo Farah wins World Championship 10,000m gold

When Serena Williams - about to tilt at the calendar Grand Slam at the US Open, 21 Slam single titles from 25 finals - winds up one of her car-crusher serves, or hits one of those mighty forehands, she has one opponent to worry about.

Farah, enjoying a similarly dominant streak on the track, has the same pressure of the grand occasion. He is also surrounded by 14 men trying to mess with his race and his head, able to sit in his eyeline or breathe down his neck, or ease an unseen elbow into his ribs.

He has one group of three working as a team, taking it in turns to hurt him, and then the same again in the vest of another nation. He has also had a heat get through just to get this far, and in Farah's case, a 10,000m final under the same immense duress less than a week before, in which the number of opponents climbs to 27.

Running isn't as difficult a skill as hitting a three-iron to six feet or volleying a ball coming back at you at 80 miles an hour, right?

Consider one tiny nuance of hundreds. If you run a single lap of a track in lane two rather than lane one - because there is no room on the curb, or because you are trying to get past a rival, let alone three of them - you are forced to run 6.8 metres further than your rival inside.

That 6.8m at the end of a race doesn't just separate gold from silver. It can separate gold from 'I'd forgotten that bloke was running'.

Ndiku (left) pushed Farah to his limits on the final lap before enjoying a playful joust in the aftermath

That is just one lap in a 12-and-a-half-lap 5,000m race. And it is only one miniscule variable in the ever-changing permutations.

We talk about footballers who have the vision to pick out the perfect pass at the optimum time. In a distance race, a champion must be capable not only of spotting what is actually happening all around them, in front and behind, to their left and their right, but to work out what those 14 rivals might be thinking of doing too.

That takes you so far.

They then need the weapons to respond to all those myriad possibilities and outcomes - not just one great tool, like the boxer who has a great jab or a fantastic ability to slip the punches, but all of them: the ability to go hard from gun to tape; to run alternating laps flat out and then slow, as opponents gang up and take it in turns to dish out the pain; to wind it up from 800 metres out; to blast out a last 400 metres that can blow the rest away.

Another frequent caveat offered by critics: Farah is only beating a limited field. The genetics required to run distance on the track are given to only a few.

So here is a list of the nations who brought at least one runner to the 5,000m in Beijing: Kenya, Ethiopia, Canada, the USA, Germany, Turkey, Japan, Australia, Spain, the Netherlands, Morocco, Norway, Brunei, China, Japan, Malawi, Rwanda, Eritrea and Belgium.

But then only the east Africans could really threaten? Well, only the east Africans have such strength in depth that they could send a team of 30 men, all of whom have the qualifying time.

There is depth within the depth, fresh danger every single year.

And what of the way victory is achieved? Farah has won many of his world and Olympic titles by surging into the lead with 500 metres to go, kicking once at the bell and again off the final bend.

It is not that the world's best runners haven't realised by now what is happening. It's that they have been unable to do anything at all about it, because Farah has been able to soak up all the ways they have tried to take that finish out of him or dictate the narrative themselves.

Farah is the first man to achieve the 'triple-double', having also won Olympic 5,000m and 10,000m titles in 2012

On Saturday night we saw a fresh test. Commonwealth champion Caleb Ndiku refused to let the Briton take it out. He led at the bell and accelerated away down the back straight.

Farah spotted it, processed it, reacted to it. He covered the last 800 metres in 1:48.6. He ran the last lap in 52.6secs.

The 5,000m makes sense to a lot of ordinary Britons. Thousands run the distance at a Parkrun every weekend, some with PBs in mind, others with dogs on a lead or kids in tow.

But those segments of Farah's are not incomprehensible only to the happy Saturday-morning dabblers. Farah's was a last mile that half the entrants in the men's 1500m would have been unable to live with. It was a last half-mile that half the 800m field would have struggled with too.

Farah does not have the world records of Ethiopian greats Haile Gebrselassie or Kenenisa Bekele. It is the one thing that arguably keeps him just shy of their legendary status.

But he has more world distance golds than Gebrselassie, and more 5,000m world titles than Bekele. And as Britain's leading light he has done it alone, without domestiques working for him, without being the kingpin in the three-man squad who have tactics and legs only for one man.

Sporting dominance can indeed appear boring. It is easy to take for granted. But only if you don't understand it.

- Published29 August 2015

- Published30 August 2015

- Published22 August 2015

- Published28 August 2015

- Published30 August 2015

- Published30 August 2015

- Published10 September 2015

- Published8 February 2019