Jessica Ennis-Hill retirement: There has been no better role model in a tainted era

- Published

Ennis-Hill took silver at this summer's Rio Games and hinted afterwards it was time to call it a day

If the timing of her retirement is no great surprise, Jessica Ennis-Hill's career has still been about the gloriously unexpected.

She won world titles and Olympic golds when she was supposed to be too small to succeed, overcame serious injuries that cost her championship chances and then came back from childbirth to triumph again - along the way beating women once banned for doping and others who were only retrospectively sanctioned.

In a tainted era, there has been no better sporting role model.

On the track, her triumph at London 2012 was one of the iconic moments of an impossible fortnight. Off it, she managed to come through the attrition of her seven-event sport and the pressures of fame as only a very few could.

Ennis-Hill's life changed forever in the summer of 2012. Her character did not. This was a woman who would give you a lift back to Sheffield station when you had been to interview her at training, who would ask to see photos of your children on your phone when you caught up, who would still greet you with a wave and a hug in the formality of a pre-championships news conference.

How Ennis-Hill inspired a nation

Like those other female icons of modern British sport, Paula Radcliffe before her and Laura Trott (now Kenny) after, Ennis-Hill critically had something else underneath that pleasant, normal exterior: a fierce competitiveness and extraordinary determination.

Sporting success was never preordained nor handed over. At the 1999 English Schools championships, aged 13, she finished 10th in the high jump.

Neither was there much glamour in the hard work that took her from minor placings to the top of the world. Training at Sheffield's Don Valley Stadium, the grandstands were always deserted, the wind usually brisk and cold, the only spectators the occasional chap in overalls pushing a lawnmower up and down the infield.

At the English Institute of Sport it was warmer but no less punishing. Seven events, seven deadly stints. Little rest, few hints of the big nights to follow in distant stadiums.

"I hate the 800m training sessions - hate them," she once told me. "They're horrible. I moan about them for the whole day leading up to them. But you feel so much better afterwards - well, you feel awful, but the sense of achievement is great."

It encapsulates the attitude that set her apart. It hurt, but it was worth it.

It was difficult, but she stuck at it - switching her long jump take-off foot from right to left after the stress fracture that ruled her out of the 2008 Olympics, which is a little like asking a right-handed golfer to suddenly putt left-handed, and then switching back to the left again seven years later when inconsistency with the new approach was identified as a medal-wrecking risk too far.

She was never alone in all this. Her expert team included physio Ali Rose, masseur Derry Suter, javelin coach Mick Hill, physiologist Steve Ingham and biomechanists Aki Salo and Paul Brice, Ennis-Hill the managing director of an extended pool of departmental heads.

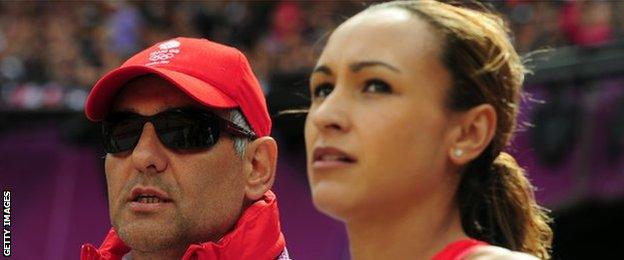

None was as central as coach Toni Minichiello, who first met her when she was brought along by her parents to a summer holiday kids scheme in 1997 and who was with her through all that followed over the subsequent 18 years.

How Jessica Ennis-Hill won gold at Worlds

On that first day at Don Valley, the 11-year-old girl won a pair of trainers for her efforts. That she went on to win a great deal more owed so much to their odd-couple relationship, two ships pulling in the same direction but having to cope too with the inevitable tension between them.

It began with Minichiello in charge. It developed into a partnership. There would be arguments, but there was also always humour. And there was always an understanding of exactly what was required to get the best out of an athlete who would never be satisfied with less.

During tough hurdles sessions, Minichiello would motivate his athlete by showing her a colourful spreadsheet of all the times she had run across different sessions, down to the exact splits between each of the hurdles, knowing that if Ennis-Hill was struggling mentally, it would inspire her to run quicker.

When his shouts of encouragement during 800m reps fell short ("It doesn't spur me on, it just makes me angry," Ennis-Hill told me in 2011. "I think, why am I doing this when you're just standing there blowing a whistle?") he would defuse and reignite with gentle mickey-taking. He once pinned up a poster from Athletics Weekly magazine of her drawn as Superwoman, and another time showed her a photo from the finish line of the 800m at the 2011 Worlds of Russian rival Tatyana Chernova towering over her like an adult scolding a child.

Ennis-Hill had won the previous world title in Berlin in 2009, external and would win the last she competed in, in Beijing six years later, yet the Daegu crown should arguably have been hers too.

Coach Toni Minichiello (left) has guided Ennis-Hill through her successful 18-year career

Chernova was later found to have been taking banned steroids. The Russian anti-doping agency retrospectively annulled two years' worth of her results, but conveniently ended that period 16 days before the 2011 Worlds began.

If that episode would have weakened the competitive resolve of many others, Ennis-Hill was not one for excuses. Trying to get heptathlon-fit again after the birth of her son Reggie, she and Minichiello invented a new statistic to measure her sometimes unlikely and often remarkable return: PPPB, or post-pregnancy personal best.

It both took her back to the top of the world in 2015 and then enabled her to cope when, at the Rio Olympics this summer, the future of her event caught up with the present and past.

Belgium's 21-year-old tyro Nafissatou Thiam set personal bests in five of her seven events on the way to winning gold. Faced with the conundrum of trying to beat a woman who keeps beating herself, Ennis-Hill realised that silver represented a triumph all the same, and that now was also the moment to say farewell.

Ennis-Hill posted on Instagram: "I've always said I want to leave my sport on a high and have no regrets and I can truly say that"

She had nothing more to prove.

There was so much more to her career than London 2012, but those home Olympics both defined her and captured what set her apart: coming out on the first morning under the most intense expectation and producing the fastest 100m hurdles ever seen in a heptathlon; overtaken by Chernova with 250 metres to go in the 800m the following evening, not needing to win the heat to secure gold but fighting back all the same.

It has framed her forever at the heart of 'Super Saturday', the central figure in British athletics' most famous triptych of all.

Seventeen million British television viewers, 80,000 more screaming down Stratford's Olympic stadium, three iconic gold medallists. Mo Farah, the immigrant kid who arrived in west London aged eight to make the capital his home. Greg Rutherford, the middle-class boy whose great-grandfather played football for England over a century ago.

And then, arms outstretched and head thrown back as she crossed the finish line, the girl from Sheffield who won against the odds and won again as a mother.

British sport, and Britain itself, has been lucky to have her.

Ennis-Hill wants you to get active

- Published13 October 2016

- Published13 October 2016

- Published14 August 2016

- Published13 October 2016

- Published15 July 2016

- Published26 June 2016