World Championships 2017: Why athletics is still worth fighting for

- Published

- comments

Gatlin wins 100m gold as Bolt finishes third

So this was a disappointing World Championships. Justin Gatlin beat Usain Bolt. Seven days later, cramp beat Bolt again. Wayde van Niekerk couldn't win his 200m/400m double. Isaac Makwala couldn't even start both.

Mo Farah, after 10 global golds on the bounce, finished with silver. Britain went fourth, external rather than conquered. Only one new championship record was set. On most days it was grey and on several nights it was as cold and wet as autumn.

It was also a Worlds where the old guard was superseded by the new in electrifying fashion. Upsets were everywhere: double Olympic champion Elaine Thompson out of the medals in the 100m, world record holder Keni Harrison off the podium in the sprint hurdles, Olympic 400m hurdles champion Kerron Clement overshadowed by charismatic young Norwegian Karsten Warholm.

There were comeback stories - Sally Pearson from a shattered wrist that almost led to amputation, South African long jump champion Luvo Manyonga from an addiction to crystal meth. Ding-dongs were everywhere - in the women's triple jump, in the long jump where six centimetres covered the first four athletes, in the women's 1500m and the men's 800m. Both steeplechases were thrillers.

So it was disappointing for Great Britain. Going into the final weekend, the largest squad they had assembled for a Worlds had just one medal to show for it, and that was Mo Farah's 10,000m title in the first night. £27m in funding over the four-year Olympic cycle, went the prevailing argument, should be bringing home so much more.

Farah wins world 10,000m title for third time in a row

And then the relays happened. Gold for the men's sprint quartet, silver for the women. Silver for the women's 4x400m team, bronze for the men. Along with Mo Farah's 5,000m silver it meant Britain finished with six medals - on its target, the same number as after the last two Olympics, at the Worlds of 2013 and 2009.

Disappointments and great excitement, a struggle but a success. This is where athletics is, and the Worlds of 2017 brought both old doubts and fresh hope.

Britain wanted more. Maybe, in a Worlds without Russia, in a sport which is possibly cleaner than it used to be, it should have taken them.

GB win gold as Bolt pulls up in 4x100m relay

Those relay medals were wonderful, each achieved through hours of drills and a tightness between the constituent parts that cannot be faked. They are also the lower hanging fruit on the track tree; only 16 teams invited for each. There is a reason they are targeted by British Athletics.

But athletics medals are hard to win. There are 208 member nations of the IAAF. It is a more truly global championships than that of track cycling or rowing, the two great engines of the British medal machine across the past three Olympics.

Last summer on Rio's Lagoa Rodrigo de Freitas, British rowers dominated the regatta, winning three gold medals and two silvers. With 43 athletes they also had the biggest team of any nation there. Forty-nine of the nations there qualified teams of fewer than 10 athletes - 32 of them had a team of just one or two rowers.

Only nine nations apart from Britain won a gold. At London 2017, 43 different nations won medals, 27 different nations gold.

Record-breaking crowds took to the London Stadium over 10 nights

Then there is the spread of the past 10 days. Five fourth-place finishes might sound like five failures, yet each was a stretch achievement for the individual who took it.

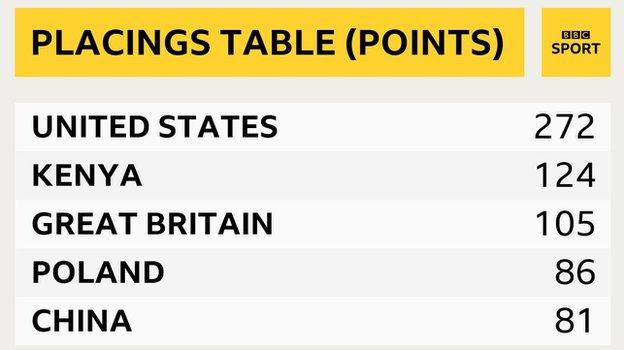

The IAAF produces something called a placings table,, external which aims to give a broader indication of each nation's strength. Eight points are awarded for a first place, seven for a second, down to one for eighth.

At the 2005 Worlds, Britain came 12th on this ranking with 35 points. Across the five Worlds since then they have hovered between fifth and seventh, their biggest total the 94 points of two years ago in Beijing.

Here in London they ended third, racking up 105 points. Maybe it means nothing compared to medals. Maybe that strength in depth won't convert to medals over the next four years. Maybe too it suggests encouragement, even as issues remain with the quality of coaching available, with the development of promising juniors into successful seniors, with the glaring gaps in several key disciplines.

There were an almost overwhelming number of reasons to be pessimistic about track and field coming to London. The end of Bolt, the ongoing struggle against doping, only the start of the complete rebuild the sport's governance and image requires.

All those issues were here right in front of you. There were several performances that wise insiders struggled to make sense of, the sight of returning cheats taking titles, athletes who have switched nationality for purely economic reasons winning medals for nations where they have never lived.

Eleven individuals and five relay teams were reallocated medals denied them by cheats in the recent past. If that was both welcome and dispiriting, so too was the warning from IAAF president Seb Coe that other nations may yet join Russia in mass exclusion from the biggest stage.

And yet impossible to ignore too were the great strengths of this beleaguered sport, the spells of magic that set it apart from others, the allure that still shines through when circumstances are right.

Hero the Hedgehog entertained the spectators with crowd-pleasing slapstick comedy

Over its 10 days, 705,000 people came to watch these championships. Never before has a Worlds brought in so many.

If that won't happen in Qatar in two years' time, neither does it happen in the same way at other great events in this sport-mad nation. An athletics crowd is untouchable in its diversity: families, kids, a blend of ethnicities that reflected this host city but was light years away from the far narrower demographics at Wimbledon, or Twickenham, or Lord's.

Then there is what they see: more nations brought together than at any other sporting championship, a wider range of skills and sizes, the action on those big nights happening all around the stadium at a dizzying lick.

It is both a simple sport, in that even a newcomer can work out how an event is run and won, and one with depth - running at astounding speed, throwing an astonishing distance, jumping longer and higher than we could ever imagine.

Reformed drug addict Manyonga wins long jump gold

It can be easy to let the cynicism win. Everyone is at it. Too many of these results won't last. When the Worlds leave London's embrace the magic will dissipate and with it the crowds and energy. The troubles are still right there.

So too is the allure. There are clean athletes, and there are great champions. There are nights, like Saturday, when the thrill can still be pure and unrivalled.

It can be a beautiful sport. It is worth fighting for. Don't give up on it, even when it can feel so easy to do so.

- Published13 August 2017

- Published13 August 2017

- Published13 August 2017

- Published3 March 2018