World Athletics Championships: When Christie, Gunnell & Edwards ruled the world

- Published

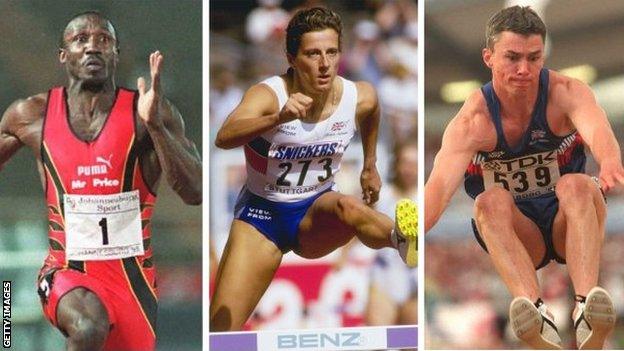

Linford Christie, Sally Gunnell and Jonathan Edwards

2019 World Athletics Championships |

|---|

Venue: Khalifa International Stadium, Doha Dates: 27 September - 6 October |

Coverage: Watch live on BBC TV, BBC iPlayer and BBC Sport website and app; Listen live on BBC Radio 5 Live; Live streams, clips and text commentary online. |

When British athletes take to the track and field in Doha this week, a select few do so with tangible medal ambitions.

Think super sprinter Dina Asher-Smith, magnificent miler Laura Muir and multi-event marvel Katrina Johnson-Thompson. All will harbour hopes of gold, albeit Muir's challenge might be tempered by recent injury.

But topping the podium for each is rooted in just that - hope. There is a certain anticipation of a certain success. But it isn't a pressure that readily comes the way of such rivals as Elaine Thompson, Shelly-Ann Fraser-Pryce and Nafi Thiam, all of whom have conquered the world enough times to burden them with golden expectation.

It is expectancy three greats of British athletics know all about. Linford Christie, Sally Gunnell and Jonathan Edwards delivered world titles in Stuttgart in 1993 and in Gothenburg in 1995 and helped create a golden age.

This is what expectation of 'certain' gold looked like about a quarter of a century ago.

Christie and Gunnell had celebrated glorious gold at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. Christie won the blue riband event, no less - the men's 100m. Watched by an American basketball dream team - driven by the often-airborne Michael Jordan and trash talking Charles Barkley - and tens of thousands of others (a fortunate me included, on my first overseas trip with BBC Sport), Christie destroyed US favourite Leroy Burrell to become just the third Briton to win this coveted crown.

In a dash-and-be-damned world of critical fleeting moments, Christie seized his. Christie felt the American was there for the taking after the semis, where he calmly stayed with Burrell without feeling the need to pass him. He would save that for the final.

"I knew I could have passed him," said Christie. "And I also knew if I got out in front, no-one could do the same to me at the back end of the race."

Christie was never lacking in confidence. His was now sweeping and soaring over Montjuic Park.

When Burrell false-started before the gold medal showdown, Christie knew he had his man.

The American was the fastest in the field. But not when it mattered. Not when the pressure was on. Christie was Olympic champion.

Sally Gunnell claimed gold in the 400m hurdles at the 1993 World Athletics Championship in Stuttgart in a new world record time

Gunnell took to the blocks in the women's 400m final facing a similarly favoured American, Sandra Farmer-Patrick. But there was no doubting the outcome for Gunnell either.

"I knew I was going to win," she told me. "I can't really explain it. I just knew it."

Farmer-Patrick had been the fastest woman in that event that year. But not when it mattered. Not when the pressure was on. Gunnell was Olympic champion.

Fast forward to the World Championships of 1993. Christie and Gunnell were the favourites now. They were Britain's golden duo - bigger than any Premier League footballer might currently profess to be - and were many times front-and-back-page central. Both were expected to win more gold in Germany. To finish second was to be branded 'failure'.

Carl Lewis had not made the American team for the 1992 Olympics, but was back for the worlds. The 100m final field was loaded. Christie was chief among them.

Once again, I was a privileged and mesmerised spectator. The stadium was heaving, 60,000 similar expectants in all. The silence as the bold and the buffed surrendered to the blocks was astounding. Not a sound. Not a single whisper. And then, as only happens in the men's 100m, gunfire shattered the silence and less than 10 seconds of rising sound followed.

When all the noise was done, Christie was world champion. Not Carl Lewis. He was a distant fourth. Not the other American wannabes, Andre Cason and Dennis Mitchell. They were second and third respectively.

Linford Christie became the oldest 100m world champion at the age of 33 years 135 days by winning gold at the 1993 World Athletic Championship in Stuttgart

Christie set a UK record of 9.87 seconds, a mere 0.01 off the world record. He never ran faster. No Briton ever has. At 33 years and 135 days old, Christie became the oldest world sprint champion in history, just as he had become the oldest Olympic men's 100m champion the previous year. When others of a similar age might be gently shouldered off the stage, Christie was carrying the world on his shoulders.

"This was my greatest win," said Christie. "People might think the Olympics would be, but there was something about that World Championships race. It was special." And in case we needed reminding, he quickly and proudly added: "My British record still stands to this day."

Christie's victory had made Gunnell's task all the more pressurised. If one Olympic champion triumphed then surely the other would follow. That's how things had to work in this new world of British athletics' golden synchronicity. "Gunnell goes for gold and Gunnell gets the gold" all over again.

But Stuttgart, we had a problem. Gunnell may have been in the form of her life in 1993, but illness can make a mockery of an athlete's peak. She woke, one morning during the championships, a less than super Sal. A cold had set in. Nothing more than that, but enough to have the best questioning whether this malady might only allow her to be second best. For a while, withdrawal seemed the only option. A press conference was being arranged to that effect.

But growing up running free on a 365-acre farm does not a quitter make. Gunnell thought again. To run was to have no regrets - no "what ifs" in later life.

On 19 August, 1993, Sally Gunnell was there for Britain in sickness as she had been in health in Barcelona. On 19 August, 1993, Sally Gunnell won World Championships gold in a world record time of 52.74secs. Farmer-Patrick was again a silvery second.

"I didn't know I'd won when I crossed the line," Gunnell recalled. "People say to me, 'How could you not know'. But I was just in my own world. I didn't know I'd broken the world record until a good few seconds afterwards when someone told me as I was jogging up the track. I couldn't believe it."

It was disbelief born of running sick… of a niggling, nagging doubt that she should not be running at all.

The following day, Welsh wonder Colin Jackson set a stunning world record of his own of 12.91secs in winning the 110m hurdles final, showing what might have been in Barcelona had injury not reined in his sublime talent. Even there, his 13.10 first round Olympics run was quicker than the eventual gold medal-winning time.

No matter. Jackson had his crowning glory now and Britain had three individual golds. We would not see the like again on a global scale until that unbelievable spine-tingling night of nights on Super Saturday at London 2012, when Jessica Ennis-Hill, Mo Farah and Greg Rutherford memorably and exhilaratingly created Team GB history.

But Jackson was not weighed down in Stuttgart by expectation that came with Olympic gold. For Christie and Gunnell to produce the performances of their lives so soon after their Olympic triumphs was extraordinary.

Cementing legendary athletics status was never more adroitly achieved.

For all last year's domination of the European Championships, when she won three gold medals, Asher-Smith does not yet know what it is like to enter a global event as a standout favourite. The same is true of Muir and KJT. Win in Doha, however, and a whole new spin will be put on their build-up to next year's Tokyo Olympics. That's when they might want to dip into the Christie-Gunnell archive for inspiration.

Archivable moments in athletics have seldom come more astounding than the triple jump performance delivered by another Briton being widely crowned world champion before he had set foot on the infield.

British triple jumper Jonathan Edwards has held the world record in the triple jump event since winning gold at the 1995 World Athletics Championship in Gothenburg

The 1995 World Championships were held in the welcoming Swedish city of Gothenburg.

The British gold mark standard now belonged to one Jonathan Edwards. He was the new world record holder, set in Salamanca, Spain after a few warning shots from the bows of windy Lille in France at the European Cup (a wind-assisted 18.43m included). The winner's medal was being hung around his neck before he had taken even one hop, skip or jump at the World Championships.

You can revise until dawn and still be thrown a curveball of an exam question in your finals or have gorged on the highway code and still have a stray dog send your driving test into meltdown, so life offers few givens. Except perhaps for this man in this event in this year.

"Something magical was happening," said Edwards. "I felt I could jump as long as I needed to."

In the first round in Gothenburg, Edwards broke his own world record with a distance of 18.19m - so becoming the first man to legally leap beyond 18 metres. "Oh, it's huge, it's massive!" declared Paul Dickenson in BBC commentary.

Less than 20 minutes later, Dickenson picked up, with Edwards jumping again: "It's a tough act to follow… but he's done it again! I don't believe it!"

Edwards believed it alright. It was as if he could have broken records all night long and still have begged for more.

The Briton with built-in spring had extended the world record to 18.29m. It's a staggering mark that remains unsurpassed.

Oh, what it must be to nail a task like nothing has ever been nailed before, to find unfathomable runway speed in combination with ridiculous bound, finished off with a jump into legend.

Edwards has owned his record longer than American Bob Beamon possessed his legendary long jump world record. This is fabled status.

What Britain's medal hopefuls in Doha wouldn't give for such alchemy.

A lesson in golden expectation anyone?

Watch extended interviews with Linford Christie, Sally Gunnell and Jonathan Edwards during the BBC's coverage of the World Championships from Doha. All will also be available on BBC iPlayer.