Muhammad Ali at 70: Growing up with Ali

- Published

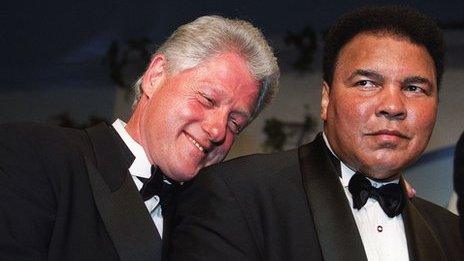

Clinton praises Ali courage

We were told we had 15 minutes. Not roughly. Exactly 15 minutes. And sure enough, almost to the second, one of his aides hollered: "That's it."

The allotted quarter of an hour included the time for handshakes, small talk and sound checks. Ex-presidents are busy boys. And impressively adept at switching subjects.

The interview took place on the 18th floor of a glass-fronted edifice in the financial district of Manhattan. The offices form the New York headquarters of the Bill Clinton Foundation and on arrival we were shown to a waiting room alongside two American TV crews.

In orderly (almost military-style) succession, Clinton gave his (15-minute) take on an Arkansas basketball coach, a female governor of Texas... and the greatest sportsman who ever drew breath.

I was the one armed with questions but the first one was from Clinton to me: "Is Ali still living in Berrien Springs?" Ali left there in 2007, moving to Scottsdale, Arizona and a more suitable climate.

Clinton had suggested such a change, recalling a night in Michigan a decade ago when Ali was still able to communicate with speech and "sat telling me jokes all night".

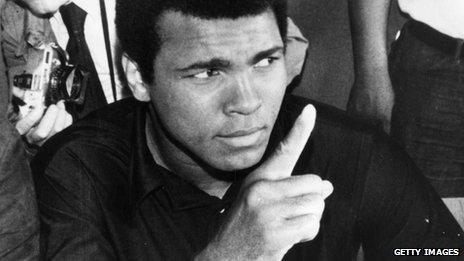

The humour, the repartee and the poetry were important components in the making of Ali. He was made for TV - and TV was made for him. It was his fortune that his professional career started to flourish as access to TV sets was mushrooming, all around the world.

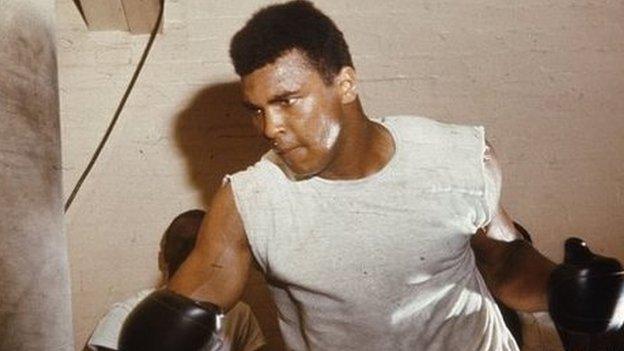

As a kid in south-east London, it seemed impossible to resist his embrace. I remember, in 1974, fearing for his safety when he took on the ogre called George Foreman. I wondered not whether he could win but whether he would survive.

My dad watched a closed-circuit screening of the fight at Lewisham Odeon and I couldn't believe it when he came home and told me Ali had won.

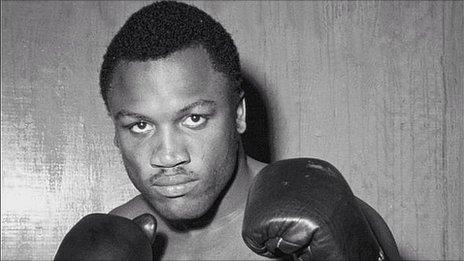

Ten years earlier, the then Cassius Clay had slain another monster in Sonny Liston. Two of the most frightening characters ever to lace on gloves had been sedated by a genius whose temperament was as strong as his chin.

And it was striking how Liston - in the rematch in 1965 - and Foreman fell to the canvas in near-identical style, tumbling face-first before rolling on to their backs.

Ali was the primary reason I took up boxing. I wonder how many more youngsters across the globe pushed open a gym door for the same reason.

It would be much later, and with much reluctance, that I would come to address the warts on the hero's story. The womanising, the demonising of white people as devils and the crudest of insults directed at opponents, in particular Joe Frazier. All of them reasons why Ali was reviled as much as revered.

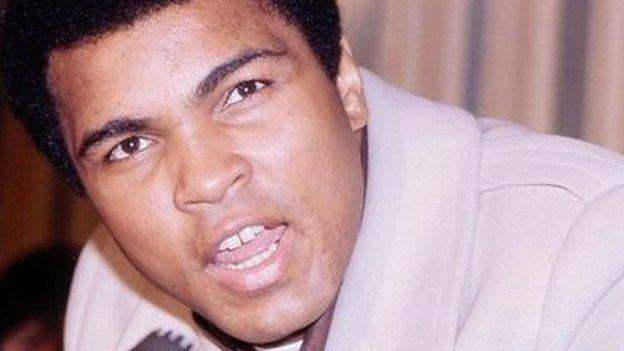

His stance has softened over time. For so long a member of the Nation of Islam, he adopted a more moderate form of his faith in 1975 and his wife Lonnie says now that he "evolved to understand that what he was preaching back then [in the 1960s] was not true Islam".

As anniversaries come and go, the debate is refuelled as to the impact Ali made outside the ring. Mark Kram wrote a withering onslaught, 'Ghosts of Manila', a book based on Ali's third showdown with Frazier.

In it, Kram derides Ali as no more of a social force than Frank Sinatra and says that today he'd be regarded as a contaminant, a chronic user of hate language and a sexual profligate.

Others, like the basketball great Charles Barkley, throw strong counters: "Ali let me know I could have opinions and express them. I cannot do justice in words to express what that meant to a young black kid growing up in Alabama."

Frazier, Ali and Foreman on Wogan

In our interview, Clinton talks about Ali's influence on either side of the ropes. Of fight nights, he remembers "a ballerina in a boxing ring".

In 1967, when Ali was forced into exile from the sport after refusing to serve in the Vietnam War, Clinton was a student at Georgetown University in Washington DC. Later, while on a Rhodes scholarship at Oxford, he took part in anti-war demonstrations.

Clinton was US president - and present - when Ali lit the Olympic flame at the Games in Atlanta in 1996. He remembers how everyone in the stadium was willing Ali to overcome the tremors and ignite the cauldron, "as if they were supporting a team".

Clinton hails the courage Ali is showing in dealing with Parkinson's Syndrome, first diagnosed in 1983. In his own book 'My Life', Clinton talks in the early chapters about his uncle Buddy, whose later years were marked by a combination of sadness and illness.

Buddy was phlegmatic about his lot. "I signed on for the whole load," he said. "And most of it was pretty good." Ali might say the same.

- Published17 January 2012

- Published4 June 2016

- Published4 June 2016

- Published17 January 2012

- Published4 June 2016

- Published24 December 2011

- Published14 November 2011