Boxer Orlando Cruz dreams of becoming first gay world champion

- Published

- comments

On 24 March 1962, a Cuban boxer called Benny Paret was beaten to within an inch of his life in a New York ring by Emile Griffith,, external a tragedy watched by thousands at Madison Square Garden and millions of Americans on television.

Consequently, Griffith, a five-time world champion and Hall of Famer, is largely remembered for killing a man - Paret died from his injuries shortly after the fight - and for his struggles with his sexuality, the two defining aspects of his life that have proved impossible to untwine., external

Many years after his retirement, Griffith admitted what many already knew, that he was indeed bisexual. Recalling his third encounter with Paret, who taunted him over his sexuality during the build-up to the fight, Griffith said: "I kill a man and most people understand and forgive me. I love a man and so many people find this an unforgivable sin."

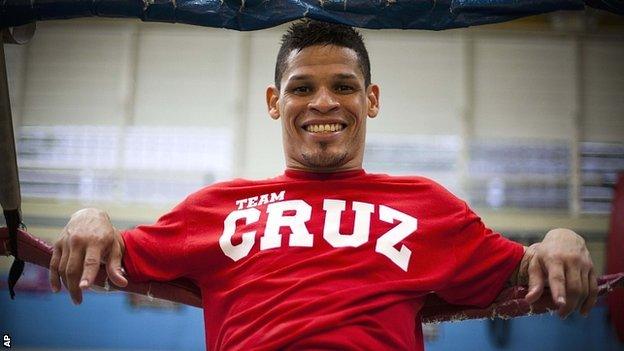

Last week, 50 years after the death of Paret, Orlando Cruz became the first active boxer to come out as gay. "I have and will always be a proud Puerto Rican," said the 31-year-old featherweight. "I have always been and always will be a proud gay man."

The Twittersphere, a notoriously spiteful place, was effusive in its support. Puerto Rican singer Ricky Martin, who came out in 2010,, external sent "hugs"; Miguel Cotto, a typical blood-and-guts Puerto Rican fighter, external and a team-mate of Cruz at the 2000 Olympics, predicted better times ahead for his "great friend".

The reaction of others in the boxing fraternity was instructive. "No-one cares," said an agitated Enzo Calzaghe when I put it to the decorated trainer that some people in the macho world of boxing might have trouble accepting a homosexual boxer. "Crack on, do what you want. You're gay? Come to my gym, no problem."

"I'd love to be the first man to promote a British gay boxer," said Frank Maloney, who led Lennox Lewis to the world heavyweight crown., external "He's a human being and he brings a whole new audience to the table. I would love to see the 'pink pound', external coming through the tills."

Some might think Maloney's comments cynical, but viewed another way they are refreshingly unpatronising. And as Maloney went on to point out, boxing has a better track record than most sports at assimilating perceived outsiders and minority groups. Perhaps a boxing gym is not such an unusual place to find a gay man, after all?

Down a crackly phone line, battling with his broken English and against my non-existent Spanish, Cruz told me he had been "scared and nervous" before making what he called his "important decision".

"Only my family and a psychologist knew but we finally decided I was ready and said 'Let's do it'," said Cruz, who fights Mexico's Jorge Pazos in Florida on Saturday and is on the verge of a tilt at the WBO featherweight crown.

"My mum is my best friend and is the first person I told. She said 'Don't worry, Orlando, I'll support you'. My father was homophobic but now he is happy with my decision. And the reaction in Puerto Rico has been good: 'It's Orlando's life, it's his decision, if he's happy, then that's nice.'

"I would tell anyone in a similar position to talk to your family and friends, get professional help and be happy."

Nevertheless, it is naive of Calzaghe to suggest that no-one cares if a boxer is gay. Having attended plenty of fights and heard spectators hurling racial abuse, it is not unreasonable to suggest a gay boxer would be subjected to similar opprobrium from unreconstructed fans.

"Why advertise it? What is the reward?" Calzaghe added. "I don't care what someone is unless they are an outlaw or a criminal."

Cruz advertises his sexuality because, he told me, he dreams of becoming the first openly gay world champion. And because he no longer wants to feel like an outlaw or a criminal, as Emile Griffith has been made to feel for most of his tortured life. That is the reward.

- Published5 October 2012

- Published11 January 2012