The GB champions going from Olympic gold to battling the boos

- Published

Boxing can turn the bright-eyed and bushy-tailed into the cynical and contorted, seemingly overnight.

Look into their jaundiced eyes, listen to their weary words and you enter a world of crossed-out, ripped-up, stomped-upon storylines.

So sup up the youthful vigour of Great Britain's glorious Olympians Anthony Joshua, external and Luke Campbell while you can. Because the flavour might run out before long.

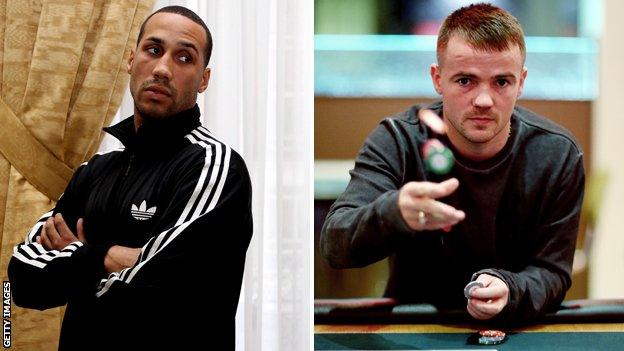

"You get back from an Olympics and you're hot property," says James DeGale, who won gold for Britain at the 2008 Games in Beijing. , external

"I'd done my country proud, I signed for the biggest promoter in Europe in Frank Warren. But after my first professional fight, when I got booed, I thought to myself: 'Right, this ain't all glitz and glamour. That stuff fades, this is some serious stuff.'"

DeGale has had to rebuild since losing to bitter rival George Groves in 2011

On 16 November, DeGale fights Dyah Davis at the Bluewater shopping centre in Kent. Vegas it isn't. Almost five years, 17 fights and plenty of lumps and bumps into his professional career, the promised land still seems a long way off.

"I definitely thought I'd have fought for a world title by now," adds the 27-year-old, who at least has terrestrial television exposure on Channel 5.

"But with politics and problems with promoters [DeGale left Warren for Mick Hennessy last September], things slowed down a touch. Pro boxing's not just a sport, it's a business - the hardest business in the world."

No British Olympic boxing champion has won a professional world title. Chris Finnegan, who struck gold in 1968,, external came closest, losing in valiant fashion to American light-heavyweight great Bob Foster in 1972.

Anthony Joshua's story

Sydney 2000 champion Audley Harrison, external entered the pro ranks believing the medal dangling from his neck doubled as an amulet but soon discovered that gold grows old, like any other colour.

Errol Christie, external never competed at an Olympics but he was one of Britain's finest amateur talents, our very own Sugar Ray Leonard. But three years into his paid career he was all but washed up and never fought for a pro title. "Christie's heart," it was written, "sets questions his chin can't answer."

Frankie Gavin was billed as a modern-day Christie - only better. Balletic foot movement, exquisite balance, the kid from Birmingham had pretty much everything. And still does, it's just that he momentarily lost it along the way.

"In the end it was so easy for me as an amateur," says Gavin, who missed out on the 2008 Olympics after failing to make the weight but remains the only British boxer to win a world amateur title., external

"I won my last 50 fights, everything was done for me at GB Boxing in Sheffield and when you're part of a team you can help each other. But when you turn pro you're on your own. I didn't realise how lonely it would be."

An unhappy boxer tends to be an underperforming boxer and loneliness exacerbated by personal turmoil made Gavin a very unhappy boxer indeed.

"I took my family up to Manchester and it was all right for a bit," says the 28-year-old. "But when I split up from my girlfriend I was doing it all on my own. And I was even lonelier."

Besides his relationship ending in acrimonious circumstances, Gavin's grandmother died and his mother was diagnosed with cancer. In addition, Gavin felt unloved by some of those charged with guiding his career.

"I remember almost falling over in front of one trainer," says Gavin, "and he said: 'I'm glad you didn't go over, that might have been my investment gone, my 10%.' It made me think.

"I was on the brink of giving it all up. I said to Frank Warren: 'I'll get back in touch if I want to box again.'"

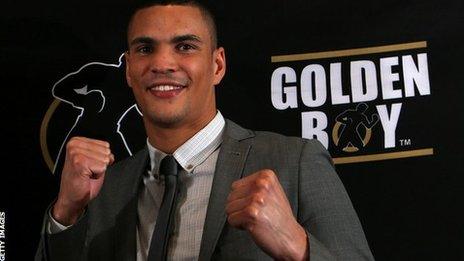

Sitting next to Gavin, with his eyes wide open and his ears cocked, is his old team-mate Anthony Ogogo, a bronze medallist at the London Olympics., external

Ogogo, on the books of American giants Golden Boy Promotions, is three fights into his pro career and as bushy-tailed as boxers come. But even he is becoming pitted by the game's hard truths.

"I've never seen anyone as talented as Frankie," says the 24-year-old. "So it's weird to think it could have been all over almost before it started.

"Then again, you hear so many horror stories in boxing - strife with promoters, trainers or managers. It's a hard enough game without all that so you need to know you've got the right people around you. People you can trust."

Boxers are wont to blame everyone but themselves for their lack of progress. So it is refreshing to hear Gavin admitting his own mistakes and that he has taken steps to rectify them. Starting with getting the right people around him. People he can trust.

"I got complacent because it all seemed too easy again, starting out in the pro ranks," says Gavin. "I thought all I had to do was box - pads, spar, pads, spar. But you've got to work on your weaknesses as well as your strengths.

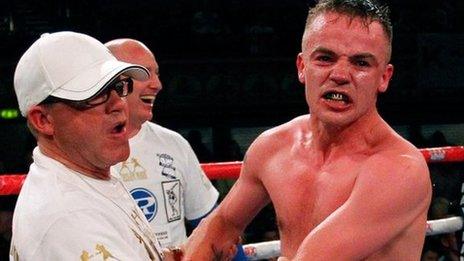

"Fighters I should have been smashing up I was having hard fights against, like Curtis Woodhouse. But when I went back to Birmingham my old amateur trainer, Tom Chaney, took over again.

"He's like a father figure to me. He doesn't nag me for money if I don't pay him on time - he's not in it for money, he's in it for me."

Head settled and body a temple once more, Gavin is now the British and Commonwealth welterweight champion and confident enough to be calling out Kell Brook and Amir Khan.

DeGale, too, is "older and wiser". Free of hangers-on, less bombastic but painfully aware he remains lumbered with something of an image problem.

"I learned a whole heap from my loss against George Groves," says DeGale of his only pro defeat, by his bitter domestic rival in 2011.

"During the build-up I was a bit too vocal, telling him he was ugly and his breath smelt. Maybe I shouldn't have said that.

"I read and hear people saying I'm flash and cocky and it does hurt a bit. Maybe it's just me being me. But the people who know me realise I'm a genuine, humble, down-to-earth boy."

Ogogo may have his eyes wide open and both ears cocked - "James and Frankie have made mistakes I don't want to make" - but the chain of advice is unbroken from the time men first laced up gloves and the same mistakes get made. Over and over again.

Gavin scraped past former footballer Curtis Woodhouse in 2011, winning on a split decision

Proof that professional boxing isn't a sport, it isn't a business, it's a series of accidents - rather than mistakes - just waiting to happen.

"I get a lot of stick," says DeGale, a former British and European super-middleweight champion and one or two fights away from a world title shot.

"People telling me I'm greedy, that I'm always thinking about money, that I've messed up my career. But they don't understand. I love boxing, but it's hard, it's a short career and I want to get paid as much as I can and get out with my faculties intact.

"I tell young fighters who train with me: 'Get in there, make some money and run.'" Which almost never happens. Not even if you turn up for your first day of work with a medal round your neck.

"It's always there," says DeGale, "I'm always 'James Degale, Olympic champion'. But another Olympics comes around, new medallists arrive and they start taking the limelight." Leaving the old guard cynical and contorted, seemingly overnight.

- Published9 June 2013

- Published30 June 2013

- Published16 January 2013

- Published2 November 2013

- Published26 October 2013

- Published11 June 2018