Carl Froch v George Groves: The thrilling, barbaric nature of boxing

- Published

Oh how they laughed, when the hype merchants said George Groves had a hope against Carl Froch. Oh how they laughed, when the hype merchants called their rivalry another Benn-Eubank. Who's laughing now? Well, nobody actually.

"There are a few things I need to grieve about," said Groves, having been stopped in controversial fashion after almost nine rounds of carnage at the Manchester Arena. "It's a bitter pill to swallow. I'm going to go home and cry."

Froch, meanwhile, looked genuinely hurt. Fat lip, the beginnings of a cauliflower ear, two black eyes. But what stung most was his tenderised pride.

"I'm devastated I got booed," said the Nottingham fighter. "But what did the crowd want to see? The kid knocked unconscious and taken out on a stretcher?"

It is a dark truth of boxing that when it is at its most compelling - its most thrilling and heroic - it is also at its most morbid and dangerous. So while nobody wanted to see anyone knocked unconscious and taken out on a stretcher, plenty did want to see everything but. Admit it or not.

"The nature of human beings is they love the barbaric side of boxing," said Froch. "That goes right back to the gladiatorial days. Nobody wants to see anybody get badly hurt. But people do want to see someone get finished off."

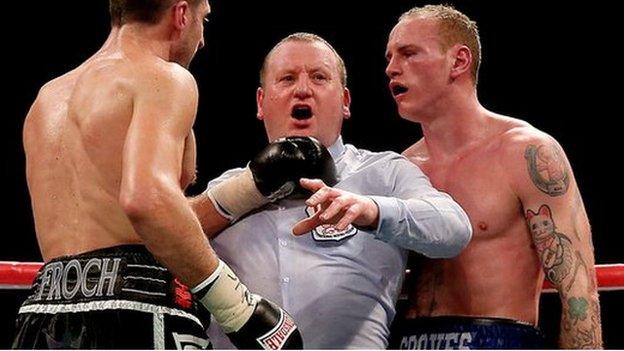

Ref Foster called a halt to proceedings in the ninth round - it was not met with universal approval

It was this dark truth referee Howard Foster was wrestling with on Saturday. When is barbarism in a boxing ring too much barbarism? It is not an exact science. Nothing can be exact when you are inches from bones being bowed, blood being spilt and brains being slopped against the inside of heads.

I recently spoke to Richard Steele, who refereed some of the most violent fights in history, including the eight minutes of mayhem between Marvin Hagler and Tommy Hearns and the bestial first encounter between Chris Eubank and Nigel Benn. Long since retired, Steele still sounded awed by the responsibility.

"It affected me a whole lot," said Steele. "The referee's job is very dangerous. You've got two kids' lives in your hands but you've got to give them every opportunity to display their talents. Fighters fight with their hearts, not with their minds, and sometimes fighters have to be saved from themselves."

Stoppage was unjust - Groves

Foster, who had to be hustled out of the arena by a phalanx of security guards, did not deserve the opprobrium that came thundering down on him.

But if you accept that boxing is a legitimate sport, then you must accept a certain level of barbarism. Foster, if anything, was guilty of showing too much compassion. There are worse things to be found guilty of.

To be challenging for Froch's WBA and IBF super-middleweight titles, Groves was, by definition, a world-level fighter. So if there was an error of judgement on Foster's part, it was in treating Groves as if he was a relative novice.

Foster did not show the same compassion to Froch when he was in a similar position, tottering backwards onto the ropes having been floored by Groves in the opening round or wearing right hand after right hand in the torrid sixth.

"Carl Froch was hurt, repeatedly," said Paddy Fitzpatrick, trainer of Groves, who was ahead on all three judges' scorecards at the time of the stoppage.

"In Howard Foster's head, that was OK, because Froch is a warrior, with a granite chin. But when George got hurt, it was a case of 'he's got a glass chin, let me jump in and save him'.

"When you jump in and make a call on people like that, it's amateurish. This is two men hitting each other. But this is a business and how people earn a living."

Foster's reputation may never recover. Steele refereed 167 world title fights but is remembered by many as the man who robbed American Meldrick Taylor against Mexican legend Julio Cesar Chavez in 1990.

Going into the final round, Taylor was miles ahead on two of the judges' scorecards but Chavez ground him down and Steele called the fight off with two seconds left. No matter that Taylor was later found to have facial fractures and was urinating pure blood for days, Steele was never allowed to forget it.

It was of some consolation to Groves that the magnificence of his performance and the sympathy over the premature stoppage saw him steal the crowd. The 25-year-old Londoner was booed into the ring and cheered to the rafters out of it, proof that there are none more fickle than the boxing faithful.

"I knew the way I'd have to behave before this fight I'd probably get booed on the way in," said Groves, who was involved in a bitter war of words with Froch during the build-up. "But I was very unlucky, and 20,000 fans agreed with me. I won their respect and that was a lovely feeling.

"The fact Carl got booed out might be the motivation he needs to give me a rematch. How many more times have I got to hit him to get his respect? He can earn a lot of money from fighting me again but it's got to come down to pride."

Froch's promoter Eddie Hearn, who agreed the stoppage was unjust, seemed to think a rematch was inevitable. "Fights are made through the demands of fans and broadcasters," said Hearn. "Everyone is going to want to see that fight again." That said, inevitable and boxing don't necessarily go.

After Eubank beat Benn in their first match in 1990, a return bout was three years in the making. Eubank, promoted by Eddie's dad Barry, figured he could make almost as much money for less risk and so Benn was left waiting.

Boos turned to cheers for Groves at the Manchester Arena

For a man who has achieved so much in boxing, Froch has always done a lot wrong, which has led to him taking a huge amount of punishment, especially against fighters with a well-versed jab and superior hand speed. Against Groves, Froch looked slow and ponderous and every one of his 36 years.

Froch, who has now engaged in 11 straight world title contests, believes he has two more fights left in him. But it might be that his trainer Rob McCracken, one of the fight game's straightest shooters, advises his old mate to jack it all in.

Millions in the bank, a large property portfolio, a beautiful partner and two kids, Froch might wonder what more boxing can give him. Other than more scars, more cracked bones and an inability to remember how he got them. And then he'll hear those boos. Pride is a dangerous thing.

- Published25 November 2013

- Published24 November 2013

- Published24 November 2013

- Published11 June 2018