Carl Frampton: The boxer following where McGuigan dared to tread

- Published

Frampton expects 'dangerous' fight

Carl Frampton v Kiko Martinez |

Venue: Titanic Quarter, Belfast. Date: Saturday, 6 September |

Coverage: Commentary on BBC Radio 5 live from 22:30 BST, or via BBC Sport website & app, and BBC iPlayer Radio app. |

My taxi driver, previously loud and hearty, fades to a hesitant whisper as the guns grow bigger above us. Guns wielded by men in balaclavas, bookended by the words: "Prepared for peace. Ready for war." Only a mural, but real enough.

A short trot down the Shore Road in north Belfast, situated in the staunchly loyalist enclave of Tiger's Bay, is the Midland Boxing Club. No gun-wielding men daubed on its exterior, just a kid in boxing gloves, proud as punch in an Ireland vest. If you thought the adage that boxing unites was trite, you should pay a visit.

Behind the doors, the kid in question is all grown up. And from the way Carl Frampton makes the heavy bag hiss and shudder, he is ready for war and peace can wait. So pity Kiko Martinez, whom Frampton challenges for the IBF super-bantamweight title in Belfast on Saturday.

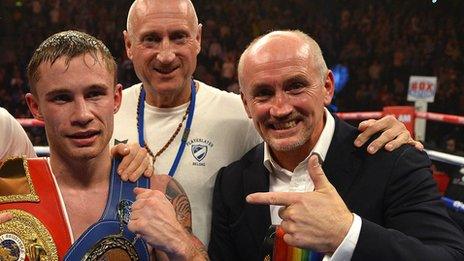

Watching the 27-year-old intently is his manager Barry McGuigan, a former featherweight world champion and a hero to all of Ireland. Smart in a shirt and jacket, but set up to fight: feet perfectly positioned, head twitching, rolling with the blows.

McGuigan won the IBF featherweight title at Loftus Road in 1985, a fight watched by 20 million

"I don't want to boast about him too much," says McGuigan, "but when people get to know him, they're going to really love him. He's a bright kid, likeable, funny and he can really fight. He's a very special talent, no question about that."

Frampton doesn't fight like McGuigan used to fight. Both men can punch but whereas McGuigan was an all-out pressure fighter, Frampton can box going forwards or backwards. But beyond the ropes their stories are strikingly similar.

McGuigan was a Catholic from just south of the border who won a gold medal for Northern Ireland at the 1978 Commonwealth Games, fought for Ireland at the Olympics, married a Protestant and took British citizenship.

Frampton is a Protestant who won two Irish amateur titles (boxing, like rugby union, is an all-Ireland sport), a silver medal at the 2007 European Amateur Championships, married a Catholic and lives part-time in England.

"Carl is doing what I did," says McGuigan, whose son Shane, himself a former Ulster champion, is Frampton's principal trainer. "He's a beacon for peace and reconciliation and represents the future of Northern Ireland. Albeit, it's not as treacherous at the moment - we don't have the Troubles like we did back then."

McGuigan remembers when the gun-wielding men in balaclavas were a very real presence in Belfast and not restricted to murals. But even when there were soldiers on the streets, paramilitary groups exploding bombs and innocent people being killed, boxing managed to cut through the carnage.

Frampton's journey so far | |

|---|---|

Born | 21 February 1987, Belfast, Northern Ireland |

Family | Lives with wife Christine and three-year-old daughter Carla in Lisburn |

Connections | Managed by Barry McGuigan, trained by Barry's son Shane in London |

Amateur record | 125 fights, 114 wins, 11 defeats; two-weight Irish champion; European silver medal 2007 |

Pro record | 18 fights (13 KOs), 18 wins |

Pro honours | European & Commonwealth super-bantamweight champion |

"Growing up I'd hear stories about Barry boxing in the loyalist club on the Shankill Road, wearing the green vest with a shamrock on," says Frampton, who was born two years after McGuigan beat the great Eusebio Pedroza to claim the IBF featherweight crown, a fight watched by a television audience of 20 million.

"This was at the height of the Troubles, when the Shankill Butchers, external were around. But when it comes to boxing, no-one says a dickie bird.

"When Barry turned pro, there was that old saying: 'Leave the fighting to McGuigan.' It doesn't sound much, but when he was fighting, the trouble in the streets would stop for a couple of hours. He was a hero for both communities."

McGuigan boxed his first senior international, against East Germany, in a working men's club on the Shankill Road in the mid-1970s.

"There I was, a Catholic guy from the south boxing right in the heart of loyalist Belfast with the Troubles at their worst," says McGuigan, still amazed at the thought of it. "We beat the East Germans, my dad got up and sang and it was a brilliant night. Boxing was the one thing then that could unify people."

Almost 40 years on, what were a few twinkles on the Shankill and elsewhere have burst into light all over the land. But while Northern Ireland is an infinitely more peaceful place than it was, it's not quite goodbye to all that.

Boxing unites people - McGuigan

The house where Frampton grew up is in a so-called interface area., external The unionist Tiger's Bay is separated from the nationalist New Lodge by 30ft-high fences, designed to repel petrol bombs and other missiles. On one side of the divide are Union Jack flags and kerbstones painted red, white and blue; on the other side are Irish tricolours and murals depicting republican martyrs. To an outsider, it is forbidding.

"The quickest way from Tiger's Bay to Belfast city centre is through New Lodge but I wouldn't go that way when I was a kid - you'd take the long way round," says Frampton. "I saw a lot of trouble. Riots would break out in an instant. It was dangerous, but when you're a kid it's exciting; you want to see it.

"A friend's brother, Glen Branagh was his name, lost his life in a riot. He was only 14. I tried to stay out of all that stuff as much as I could but when something like that happens, you don't want to see anything like it again."

On the other side of the fence is the famous Holy Family Boxing Club, which Frampton started visiting as a young kid. But he still remembers the first time he made the trip on foot, a measure of how momentous that short trip was.

"It was only a five-minute walk but we'd always go by car," he says. "But one day I was going over to spar and an old trainer from the Midland said we were going to walk in. I didn't want to. I was a wee bit shocked."

Frampton knocked Martinez out in the ninth round when they first met in Belfast last year

Holy Family's head coach, the venerable Gerry Storey, had been waving his olive branch for decades., external And between his four walls, Frampton was respected for what he was - just another working-class kid who wanted to box.

"We all knew we were in a tough sport," says Frampton, whose best man was the impish Paddy Barnes, a product of Holy Family, a two-time Olympic bronze medallist and a two-time Commonwealth Games champion.

"So it was a case of 'cut all the other nonsense out, boxing's tough enough without all that'.

"I get asked all the time, 'would you have liked to have boxed for Great Britain?' And the answer is no. I was looked after by Irish boxing from pretty much 11 years old and was very proud to box for Ireland."

From the doorstep of his parents' house, Frampton can see the tops of the Harland and Wolff cranes, 'Samson' and 'Goliath',, external only half a mile away.

During the shipyard's heyday, labourers from Tiger's Bay made up the bulk of its workforce. Things got worse for the neighbourhood before they got better but that story has been told and a more uplifting chapter has started to unfold.

"There's still a bit of tension here," says Frampton, who now has a house in Lisburn, just south of Belfast, which he shares with wife Christine and daughter Carla. "But mostly it's fine now. I'm very proud to say I'm from Tiger's Bay."

Beneath those same cranes on Saturday, next to where the Titanic was built and launched,, external Frampton will attempt to hammer and bend Martinez to his will.

Frampton has already outgrown Belfast's indoor arenas and his fight against Martinez, whom he knocked out last year (in that weird way boxing works, the Spaniard got a world title shot first, beating Jhonatan Romero last August to claim the IBF title) will take place at a purpose-built arena holding 16,000, making it Northern Ireland's biggest ever boxing gate.

Dethrone Martinez and Frampton will become his country's first bona fide world champion since Wayne McCullough in 1996., external But that's only the beginning.

"A world title fight at home at such a historic venue, a stadium built especially for me, it's hard to believe," says Frampton. "And it's very humbling to know that so many people are supporting me from all over Ireland and mainland UK.

"But once you reach that goal you have to start setting new goals. There are a few guys to be taken care of at super-bantamweight, so the next goal is to unify the division. After that, I want to become a two-weight world champion."

When our interview is done, an old boy covered in loyalist tattoos pulls up in his car, climbs out and heartily greets McGuigan. Little kids throw down their bikes, run home for scraps of paper and return for Frampton's autograph. It's a peaceful sight.

- Published1 September 2014

- Published4 April 2014

- Published17 October 2013

- Published19 October 2013

- Published9 February 2013

- Published11 June 2018