Carl Froch retires: In praise of British boxing's 'throwback fighter'

- Published

- comments

Froch was booed before his rematch with George Groves but sent the crowd home happy

Fighting Carl Froch must have been like being pursued by a boulder, gathering speed through a tunnel.

Most who turned to brace themselves got flattened. Some who ran got splattered as they grasped for the light. The most tenacious reached the exit. But only the fleetest had their hand raised after the trauma.

When fans of Froch - often of an older vintage, men who remembered way back when - called him a "throwback fighter", it was the highest of compliments.

It conjured images of gushing blood in black and white. Tough men administering terrible beatings or admiring their art, splashed across a canvas. Men who fought anyone, anytime, anywhere. And never made it easy. Men who took lickings and kept on ticking. Until time retired them.

Carl Froch floors George Groves

Boxing is timing, in and out of the ring. When to throw and when to feint. When to pour it on and when to rein it in. When to gird your loins for one last shot and when to walk away. In hanging them up now, Froch has timed it right.

Recently stripped of his last remaining world title because of inactivity, Nottingham's finest is also out of viable options. Julio Cesar Chavez Jr held the keys to a dream fight in Las Vegas but the Mexican was knocked out in April, external - and thus the keys were lost.

British rival James DeGale, who picked up Froch's old IBF title in May, was keen on a match-up. But Froch was smart enough to realise that DeGale might cause him problems and complicate his legacy.

Froch's promoter, Eddie Hearn, said the manager of middleweight king Gennady Golovkin had been phoning every day. But taking on Golovkin, who has 30 knockouts from 33 fights, after more than a year out of the ring would have been risky in the extreme. The smell of crisp sheets and a partner's sweet embrace at 6am can prove surprisingly debilitating.

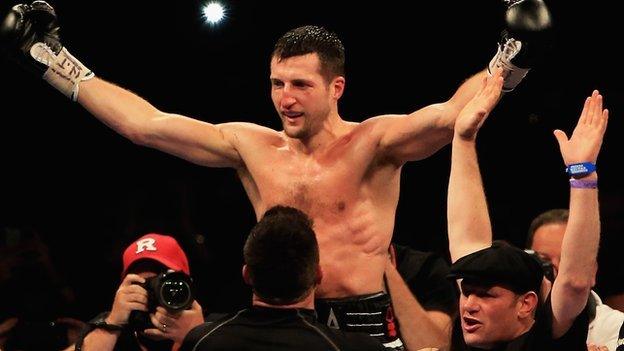

Froch knocked out Jermain Taylor with seconds to go when they fought in the United States in 2009

Froch is an old athlete at 38 but has engaged in only 35 professional fights. However, he was no will-o'-the wisp between the ropes.

If you are good enough to dance around trauma like Floyd Mayweather, why not dance on until you are knocking on 40? But Froch was always more of a grinder than a dancer - and even the most durable grinding wheels turn to dust if they stay grinding for too long.

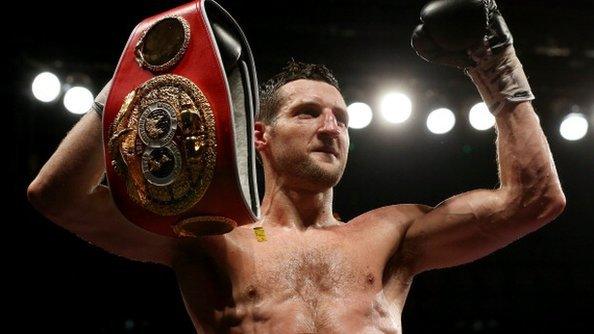

Between winning the WBC super-middleweight title after a barnstormer against Jean Pascal in 2008 and knocking out George Groves at Wembley Stadium last summer, Froch engaged in the most gruelling sequence of fights of any British boxer in living memory.

Not since Jack 'Kid' Berg, external was sticking it to New York's finest in the 1930s had a British fighter tried to chew on so much.

There was the last-gasp, come-from-behind knockout of former middleweight king Jermain Taylor, in true Rocky style. There were demolitions of Arthur Abraham and Lucian Bute. There were two ding-dong fights against Mikkel Kessler - the second of which produced fireworks that spelled out 'revenge' over London's O2 Arena.

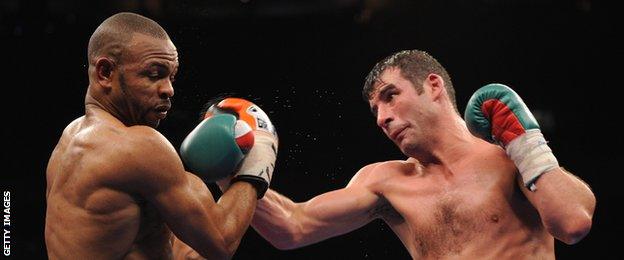

Only Kessler - in their first encounter - and Andre Ward beat him, although Ward's fellow American Andre Dirrell also gave him fits. All three had fast hands and good lateral movement. Froch preferred opponents to be standing where he wanted - right in front of him.

Froch's life in boxing |

|---|

Born: Nottingham, 2 July 1977 |

Amateur honours: ABA middleweight champion, 1999 & 2001; World Amateur bronze, 2001 |

Turned pro: 16 March 2002 |

Pro record: 35 fights, 33 wins (24 KOs), two defeats |

Pro honours: Former English, British, Commonwealth, WBC, WBA, IBF super-middleweight champion |

Best wins: J Pascal (PTS, 2008); J Taylor (KO12, 2009); L Bute (KO5, 2012); M Kessler (PTS, 2013); G Groves (TKO8, 2014) |

Fellow Brit Groves thought he had the formula, especially when he had Froch down in round one of their first encounter.

Groves, 10 years younger and appreciably quicker, made Froch creak like an old galleon for eight and a half rounds. But Froch's powers of recovery were even more formidable than his whiskers. And perhaps Groves was only stopped, in controversial fashion, because the referee knew what Froch was capable of down the stretch.

While Froch was rarely in a bad fight, his critics called him basic. True, he was more cave man than 'Cobra', the moniker he gloried in. But why get overly technical when you have a concussive right hand, the strength of a bull and the pain threshold of a brick? Just ask Groves.

But it was less Froch's technical limitations and more his poor promotion that delayed his move into the mainstream. As recently as 2010, Froch was fighting on a fringe satellite channel. His first three fights in the Super Six super-middleweight tournament, in which Froch eventually finished runner-up to Ward, were watched by tens of thousands.

Only when promoter Eddie Hearn plucked him from obscurity, stuck him on Sky and started plugging him from the rooftops did he finally get his due. And even then there were those who didn't take to him.

He was called arrogant - not to mention deluded - when he chased a fight with Joe Calzaghe towards the end of the Welsh legend's career. And he was called the same a few years later, when he suggested his achievements "eclipsed" Calzaghe's, or those other great British super-middleweights of the 1990s, Nigel Benn and Chris Eubank.

Welsh great Calzaghe (right) retired in 2009 with an unbeaten record from his 46 professional fights

For the record, most wise observers think Calzaghe would have boxed Froch's head off, just like Ward did. But fights between Froch and Benn or Froch and Eubank would have been sights to behold. Ding-ding, take cover, hold hands and hope you don't have nightmares.

Calzaghe had the superior skills and is thought by many to be Britain's most gifted boxer ever. But Froch provided more bang for the punters' buck than almost any other British boxer of the modern era.

Still, there was a telling moment in Las Vegas, a few days before Mayweather beat Manny Pacquiao (an underwhelming drama, the kind Froch rarely took part in). Froch was in the media centre when the venerable Bernard Hopkins strolled in, bounded over and showered Froch with compliments. Froch was chuffed and wore a look that said: "Look everybody - the great Bernard Hopkins knows me!"

Even after 12 straight world-title fights and starring in some of the most stirring ring battles in recent history, Froch was hungry for validation. And if he is fond of talking about himself,, external then no wonder, given that he was ignored for so long.

Froch lacked the earthy charm of Ricky Hatton, the showmanship of Eubank, the dark menace of Benn or the conjuring tricks of Naseem Hamed., external He came across as a sensible bloke - and in the inverted world of boxing, sensible blokes are marked down as suspicious characters by those who savour the sport's inherent absurdity.

But those who really appreciated boxing appreciated Froch. There might have been boos when he entered the ring before his rematch against Groves last summer. But Froch sent most of the record 80,000 crowd home happy courtesy of an "I was there" knockout, which doubled as a punishment for a lack of gratitude shown by the few.

It was the perfect way to sign off - cause a big crash and slip away from the wreckage. Faculties intact, a beautiful family to go home to, bundles of cash making even more money in bricks and mortar. Not what you would call a stereotypical boxing story - and all the more heartening for it.

- Published14 July 2015

- Published14 July 2015

- Attribution

- Published14 July 2015

- Published13 July 2015

- Published14 July 2015

- Published22 May 2015

- Published19 May 2015

- Published27 March 2015

- Published8 May 2015

- Published11 June 2018